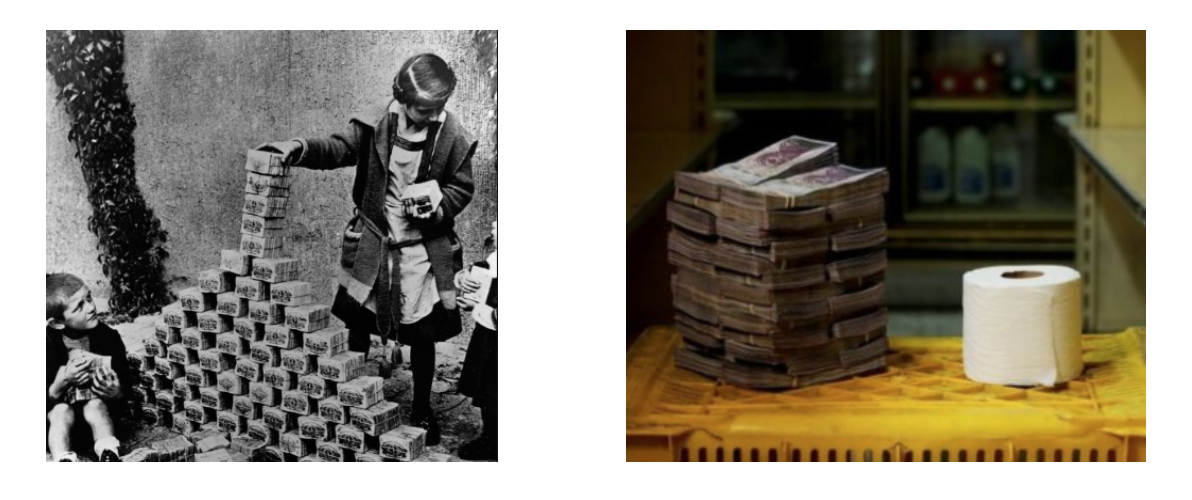

Dresses made of paper money. Children playing games with blocks of cash in the street. Hundreds of bank notes for one roll of toilet paper. These are signs of hyperinflation or when the rate of inflation accelerates at such an extradorinaiy rate it renders currency useless and creating intense Economic Disaster.

In August, according to the New York Times, Venezuelan inflation was at 32, 714 percent and rising. Prices were doubling every 26 days on average, according to BBC World News. Coffee prices had soared to 2.5 million Bolivars as Venezuelans resorted to electronic transfers via credit cards to avoid lugging around large amounts of cash.

In an attempt to slow climbing prices, the government issued new banknotes and announced that they would lop off 5 zeros off the currency. The Venezuelan government hopes this change will help deter what economists have grown to call the “wheelbarrow” problem, when prices increase to a point where wheelbarrows of paper money have to be wheeled in to afford the simplest of items.

Weimar Germany had a huge ‘wheelbarrow problem’. “A few million marks meant, nothing really. It was just that it meant more lugging,” described artist George Grosz in an interview about his experiences. “The packages of money need to buy the smallest item had long since become too heavy for trouser pockets.”

By November of 1923, it took a trillion marks to make one US dollar, according to PBS.The German mark was rendered essentially, useless. The German people used marks as wallpaper, toys, and fuel for household hearth and returned to bartering with loaves of bread and potatoes. In order to combat further disaster, the Weimar government lopped off zeros of currency and issued a new currency- the Rentenmark.

However, when it comes to inflation and the economic medicine prescribed as a remedy to that inflation, one variable is important to remember: belief. During the days of hyperinflation, the German people did not trust that inflation would slow down, and spent fast and recklessly. “One had to buy quickly because a rabbit, for example, might cost two million marks more by the time it took to walk into the store,” said Grosz in an account.

Did the German people believe in the new Rentenmark? “I remember,” recounted one German woman, “the feeling of having just one Retenmark to spend….Just to buy something that had a price tag for one Mark was so exciting.” The Retenmark eventually returned German currency to pre World War I exchange rates at 4.2 Rentenmark per US dollar.

Will the Venezuelan people believe in the new currency? The story is more complex than it appears. According to the United Nations, 2.3 million Venezuelans have fled to neighboring countries. Venezuela’s inflation has helped contribute to other problems as well: water shortages, power cuts, and supply shortage caused by lack of foreign investment in Venezuela’s infrastructure, according to the BBC. While the German government of the late 1920’s was able to stabilize both it’s country and it’s economy, Venezuela will have to solve these issues in addition to it’s wheelbarrow problem.

Sources:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-36319877

https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/hnplatimes/docview/161560392/fulltextPDF/3D5CFD9C41B047ABPQ/1?accountid=14749

https://www.facinghistory.org/weimar-republic-fragility-democracy/economics/personal-accounts-inflation-years-economics-1919-1924-inflation