Think of the Coca Cola bottle you saw on the beach in Santa Monica: after your encounter with each other, it was collected by an old man, then sent to some Southern California recycling center. Next, it went through several rounds of examination before it was put into a container, together with a Pepsi-Cola bottle and other less famous ones, to be shipped away. Two weeks later, it arrived in a coastal village in southern China.

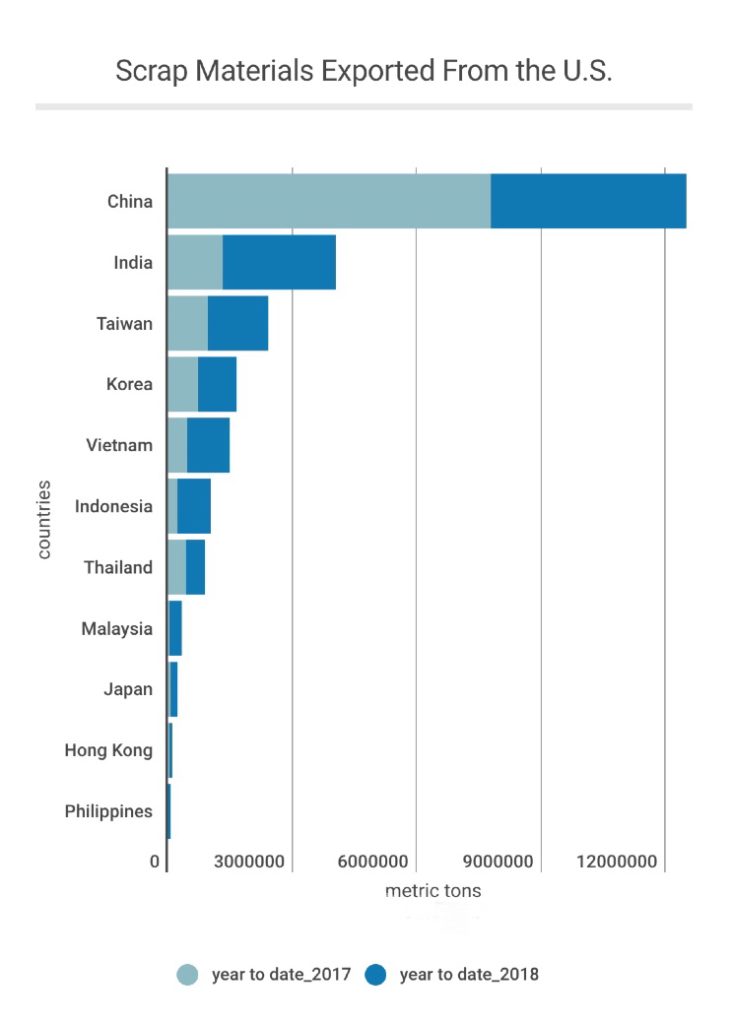

In 2017, the United States exported 11 million tons of scrap materials with a value of 5,613 million dollars to China. (source: U.S. Department of Commerce/U.S. International Trade Commission) That is one third of the country’s total export of scrap materials.

Starting from this year, China banned the imports of most categories of recyclable plastics. The waste, parings and scrap of plastics exported to China have dropped 92% over the first eight months of 2018. The policy shift has impacted the United States on multiple levels.

California has banned plastic straws statewide. Sacramento cut back on which plastics it will pick up for recycling, and will send items like egg cartoons, medicine bottles and some yogurt containers to landfills instead. Brett Johns is the Director of Sales, Marketing, and Procurement of City Fibers, a recycling company in Los Angeles. He said they are feeling the effect of the ban: “We are shipping a lot less to China, and what we are shipping to China has to meet new requirements and specifications. Price has been drastically reduced. We’ve been shipping to a lot of other countries to offset the loss.”

The Institute of Scrap Recycling Industry (ISRI) estimated that recycling industry creates 51,139 jobs in California. In 2017, 4,275 jobs are supported by export activities. China’s restriction on the import of plastic waste put huge pressure on employers in the local businesses. Mr. Johns said his company would have to the eliminate probably ten to twenty percent of human jobs positions and replace them with atomized machineries.

All of a sudden, the once invisible garbage became an eyesore. Recycling centers are now seeing stocks of trash packages. Containers filled with “trash” need to be either taken by another country or buried and burnt. Vietnam, India and Korea has become new destinations for the giant ships. After China’s ban, these regions and countries would only take in the recycling materials with lower price. “China is the biggest buyer before. When the biggest buyer put on the brake, the price is bound to be affected.” Said Mr. Johns.

Situation here is distressing enough. What makes it worse is the fact that no countries really have the capacity to digest the scrap and waste we have produced. The piles of wastes never disappeared no matter how much money people pay, or where they were shipped to. The reality of recycling industry is much less pleasant than it sounds. China had no magic to resolve the issue.

Back to the Coca Cola bottle again – what it saw in that Chinese village were smelly, dirty trash mountains populated by files. Villagers run household-recycling workshops there, right in the piles of plastic and alloy. This is recorded in the documentary Plastic China. There is a sharp contrast between these recycling centers and the ones in the U.S., which are populated by organized assembly line, tall machines and workers with masks and uniforms. Jiuliang Wang, director of the documentary Plastic China, describe the place as “a city of global wastes”.

“I was shocked the first time I was there” said Wang. “You could literally find all kinds of daily garbage from any developed countries in a corner of the village.” In the piles of plastics and mixed papers, there are Starbucks, Lay’s and any number of brands seen in on a supermarket shelf in the United States.

Wang intends to raise awareness among the domestic audience in China, particularly policymakers too: “Here what boosted the economy are industries with low added-value and high environmental as well as societal cost.” The award-winning film was banned for its criticism of local government’s chase for a good-looking balance sheet at the cost of people’s quality of life.

In 2017, China passed the National Sword policy banning plastic waste from being imported. Officials stated that this was for the protection of the environment and people’s health. Adam Minter, the author of Junkyard Planet, argued that China implemented this policy primarily to crack down on competitors against the virgin materials industry — the virgin materials industry and the big mining and steel companies are state-owned entities, and the recycling industry is largely private. This means the villages that once relied heavily on recycling business will be hit by this policy as well. It can get worse when the polluted village could not support other businesses such as tourism and farming activities.

The world is all in this together, and the issues do not go away by changing time and location. It remains to be seen how the new importers are processing recycling scrap. Environmental and societal costs of engaging in the business is not yet tracked. “This movie is really made for audience outside China.” Wang said: “People hardly realized that their daily wastes were transferred to the other side of the sea and that they were processed by another group of people in such an unexpected way.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.