On November 6th, 2017, The Walt Disney Company’s potential acquisition with 21st Century Fox was first announced, and since then, has been the talk of all major media platforms. Although this sale has been thrown around, on and off, for the past month, CNBC reported on December 5th that Disney and Fox could be closing in on the $40 billion deal, as early as next week. But despite this acquisition not yet being official, it alone speaks volumes about our current state of the entertainment industry, and the rapid shifts taking place in the movie business today.

“What is striking about this deal is that, presuming it goes through, it is evidence that both Fox and Disney have fully internalized how the world has changed and are adapting accordingly,” said the stratechery. In other words, networks have two options: adapt or boot, even if it means teaming up with your competition.

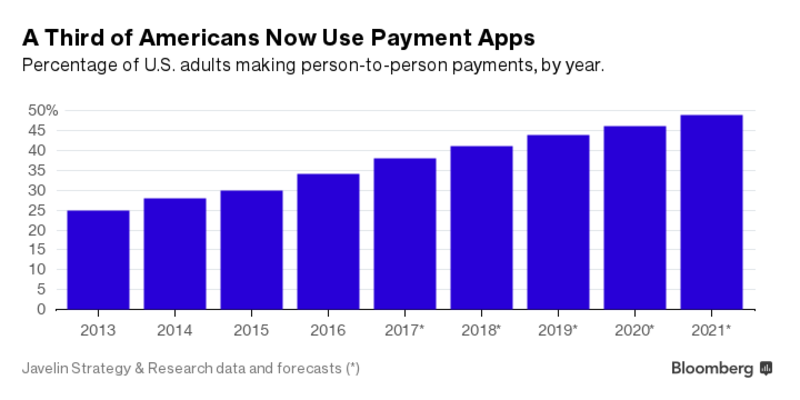

It is no secret that the internet has changed our media landscape—especially the way in which we now consume most, if not all, of our video content via online and on-demand. This change has been brought on by giants like Netflix and its rapidly growing power. So similar to how broadcast television destroyed printed content, a comparable domination is happening between broadcast TV and internet entertainment, with the latter in first place.

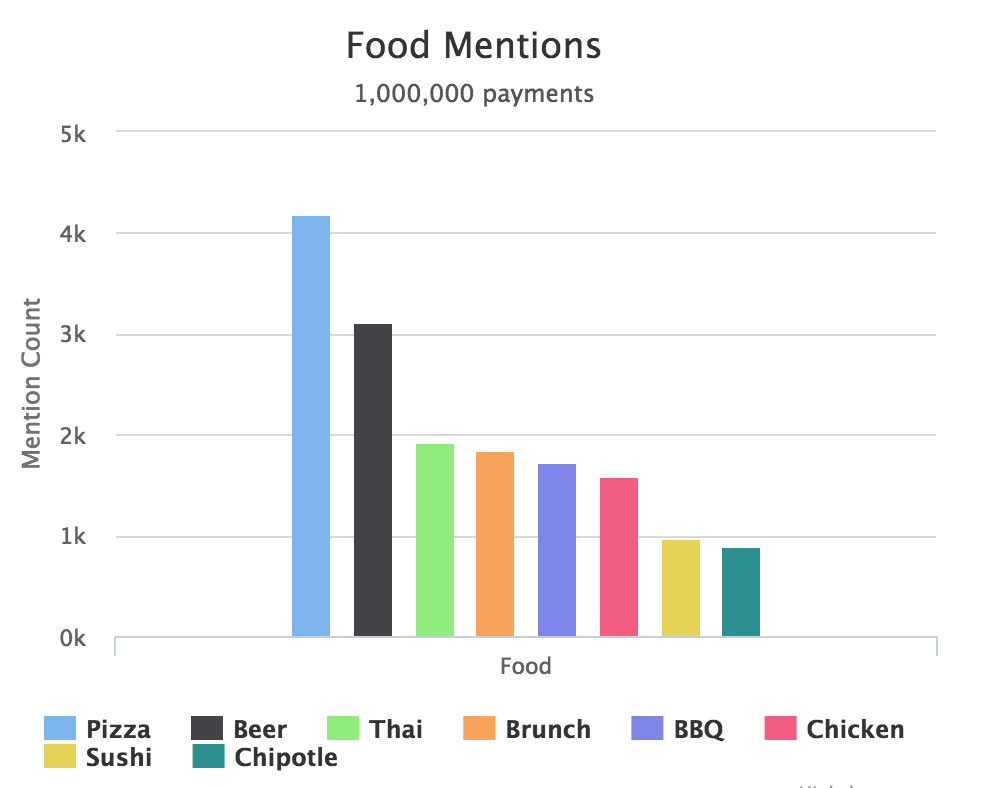

Companies like Facebook and Netflix are “dominating the digital distribution of digital video content,” as stated by CNBC, and Disney must contemplate what’s at stake to remain on top. The mutual factor in possession of power is access to its customers at the lowest distribution cost—this distribution cost has become close to zero thanks to the digital age. And access to customers is a result of providing the best user experience possible, as Netflix does—and once you provide that, you have your users hooked—and more users mean, again, all the more power.

The stratechery explained it best that “[if] selling the rights to a television show to a broadcast network and an international channel and whoever else wants it is good, then selling streaming rights to Netflix is even better! After all, the content still costs the same amount to make, and now it is generating more revenue. This, of course, is exactly what content producers did.” Disney did have its content on Netflix for some time, which was great for added reach and exposure. But they don’t just want to do “better,” they want to be the best.

It is known by most in the industry that Netflix is currently the world’s leading internet entertainment service, with more than 109 million subscribers in over 190 countries. But on August 8th, 2017, Disney announced that it will pull its movies from Netflix and create its own direct-to-consumer streaming service in 2019. Netflix’s stock dropped over $10, from $181.33 to $169.14, just two days following the news, which shows the power that Disney holds. One reason for this was due to the shareholders’ fear that other networks could follow Disney’s lead and remove their content off of Netflix as well. This announcement acted as a precursor for the Fox acquisition (this acquisition being, a step closer towards Disney’s objective to make their streaming service one that tops Netflix).

entertainment service, with more than 109 million subscribers in over 190 countries. But on August 8th, 2017, Disney announced that it will pull its movies from Netflix and create its own direct-to-consumer streaming service in 2019. Netflix’s stock dropped over $10, from $181.33 to $169.14, just two days following the news, which shows the power that Disney holds. One reason for this was due to the shareholders’ fear that other networks could follow Disney’s lead and remove their content off of Netflix as well. This announcement acted as a precursor for the Fox acquisition (this acquisition being, a step closer towards Disney’s objective to make their streaming service one that tops Netflix).

So why is Disney even going through the trouble to launch their own service from the bottom-up? This is because, again, Disney is very much cognizant about the changing landscape of media. Entertainment gravitates towards streaming, and while broadcasted television still exists, it is unfortunately dying like the print industry now. Therefore, Disney can’t just continue to do what everyone else is doing by using a source like Netflix, HBO or Hulu to stream their content on. Because Disney is, and wants to continue to be known as the forerunner of the industry, they will not settle for what everyone else is doing.

But this isn’t just about Disney becoming the next Netflix. “From a marketplace standpoint, fundamentally what [the acquisition with 20th Century Fox] does is that it allows Disney to become a bigger player in the cable arena,” said president and co-executive director of national broadcast at Mindshare Jason Maltby—as well as become more accessible and attractive to advertisers. It could “promise one-stop shopping” to marketers and ad buyers, now that Disney has reorganized their ad sales for its entire portfolio, from ABC and the Disney Channel to Freeform and Radio Disney (qtd. in Business Insider)—and with this aquisition, they will only further consolidate their company with additional networks. Also to note, if Disney chooses to dive into the advertising market for their anticipated streaming service, they will have an immense amount of revenue from that alone that Netflix does not have, as a company who is an ad-free service.

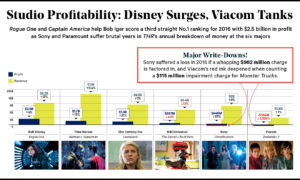

And this acquisition 100% aligns with Disney’s trajectory to be the next Netflix. First of all, in terms of success, Disney ranked number one in profitability as one of the six largest studios, with 2016 profits of $2.5 billion. The company currently “owns Lucasfilm, Marvel Studios, and Pixar, [and] already makes almost $1 billion more than its next biggest rival,” Time Warner, profiting $1.7 billion in 2016 (qtd. in The Atlantic). It is also important to note that Disney has not only been around longer than its future competitors (Netflix, Hulu, HBO Go and Amazon Studios), but has had an international presence before them as well. Not to mention Disney provides timeless content that every generation can love.

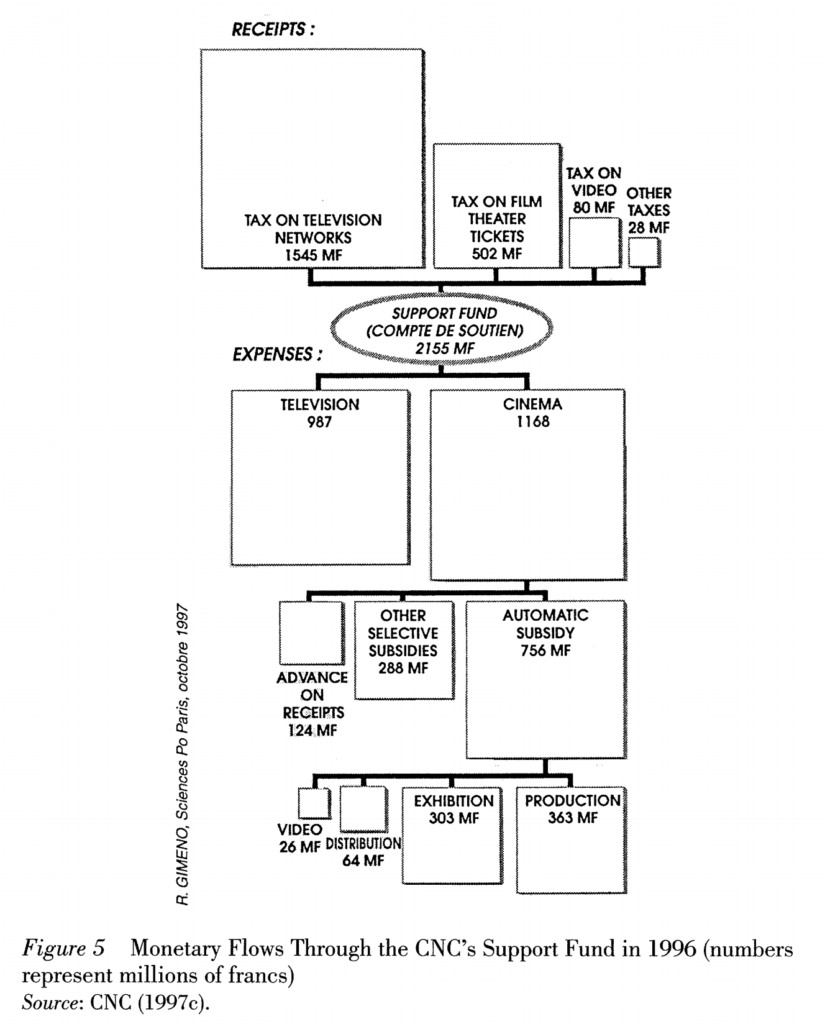

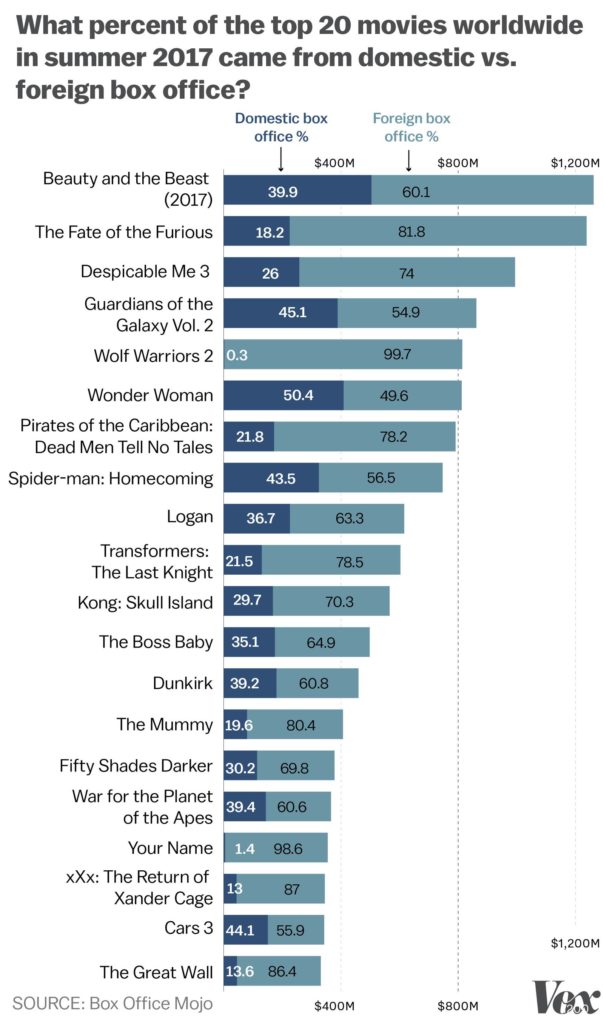

What Disney is buying is key to understanding their strategy to ensure their streaming company will be a success. They aren’t interested in purchasing 21st Century Fox’s broadcasting network or Fox News—Disney is only interested in buying Fox’s entertainment assets with an enterprise value of over $60 billion. These assets include Fox movie and television studio, the FX cable network, National Geographic, Star, UK pay-television business Sky, and their share of Hulu. Disney already owns 30% of Hulu. If they acquire Fox’s share, Disney will end up having 60% shares of the network responsible for creating Handmaid’s Tale, which took home the most wins at the 2017 Emmy’s, including in the category, “Best Drama Series.” And on top of Disney becoming Hulu’s majority and potentially full owner, the company also holds 18% of the domestic box office while Fox has 12%, according to Forbes, meaning the House of Mouse could end up with 30% of that sector of entertainment as well.

“It’s all about owning content and pipelines. And if you don’t have both, you might go out of business,”said a marketing professor at the USC Marshall School of Business Gene Del Vecchio (qtd. in Los Angeles Times).

So what else is specifically included in Fox’s entertainment assets? Let’s remember that Disney already owns the Star Wars and Captain America franchises. To put that into numbers, Captain America: Civil War made $1.15 billion in the worldwide box office market, while Rogue One: A Star Wars Story made $1.05 billion in 2016 alone. As part of the deal, Disney would also own Fox’s X-Men, Fantastic Four, and Avatar franchises, giving them control of the entire superhero world (and being able to bring that world to 24 hour, personalized streaming).

“In particular, Fox’s strong television production business would help Disney shore up its own struggling ABC Studios, which recently lost its star producer, Shonda Rhimes, to Netflix,” added The New York Times.

Fox’s logic behind selling to Disney “stems from a growing belief among its senior management that scale in media is of immediate importance and there is not a path to gain that scale in entertainment through acquisition,” according to CNBC. Disney is a company that meets this “scale” that Fox desires, who makes enough money to compete with giants like Netflix and Amazon.

So what’s going to happen to 21st Century Fox?

So what’s going to happen to 21st Century Fox?

Well, their focus will become Fox Sports and Fox News. “[Given] that both news and sports are heavily biased towards live viewing, they are also a good fit for advertising, which again, matches up with traditional TV distribution. What Fox would accomplish with this deal, then, is shedding a huge amount of that detritus,” as stated by stratechery. Basically, Fox is selling off their assets, as well as debt, to Disney, while honing in on what they do so well (news and sports), without having the pressure of competing in the streaming world.

There is concern, though, that this acquisition could be illegal, drawing attention of government regulators like the Federal Communications Commission and going against antitrust laws. Forbes defines the goal of an antitrust law, in terms of acquisitions, as a way to “prevent those that would limit the general public’s ability to make choices and receive products and services at a fair price.” An acquisition between Disney and Fox, two out of six of the biggest studios, would make the House of Mouse even more powerful than it already is. For example, their future impact on the content consumers will consume would be tremendous and potentially, unfair, depending on the company’s beliefs and biases integrated in their stories. Also, the antitrust laws brings up the notion that Disney most likely would have bought the entirety of Fox if it weren’t for legality issues, but one company cannot own two broadcast networks. Regardless, with the assets Disney strategically picked out from Fox, Disney’s already extraordinary portfolio will be bigger than ever.

Another concern is that “[if] a deal closes, marrying the two brands and two very different corporate cultures could take awhile. You have the family-friendly Disney, which doesn’t even do R-rated movies, and Fox, whose movie studio produces unapologetically hard R-rated,” as explained by Deadline. But instead of thinking of this as a challenge, it is again, broadening their portfolio to provide content that anyone and everyone can enjoy.

So if this acquisition does follow through, which seems highly likely as of now, it will be a game changer for the movie industry. First of all, the “Big 6,” six companies that own basically all media, becomes the “Big 5,” eliminating more competition. Basically, “[in] terms of sellers in the marketplace, agents, managers, producers, production companies – they have one less buyer,” said University of Southern California professor Jason Squire (qtd. in Boston Herald). Disney CEO Bob Iger will also likely “stay on past his 2019 retirement date if the entertainment company wins its bid to buy” from Fox, according to The Wall Street Journal. In fact, 21st Century Fox CEO Rupert Murdock has requested that Iger stay if the sale goes through.

Netflix CEO and Founder Reed Hastings has shared sentiments on why he isn’t concerned about how other streaming companies are doing, during a quarter one earnings call this year. He said, in particular about Amazon, that “they’re doing great programming, and they’ll continue to do that, but I’m not sure it will affect us very much. Because the market is just so vast.” Hastings is known to have a “there’s room for everybody” attitude.

It will be interesting to see if Hastings’ room for all attitude will change once Disney is officially in the playing field, or even better, beating them at their own game.