The Problem

Pursuing a degree in higher education is often romanticized. Education is revered as the investment of a lifetime, and a staple of the American dream. However, the price tag associated with this dream has either left millions in anxiety-inducing debt or deterred people from pursuing a degree at all.

In 2016, The White House released a study that evaluated the benefits and challenges of student debt. According to the study, “the average full-time worker over age 25 with a bachelor’s degree earns nearly $1 million more than those with a high school diploma.” Therefore, those with more debt due to pursuing a master’s degree, M.D., or J.D. will have greater ability to pay off their debt over time. This should make us feel better; it is statistically proven we will not be in debt forever. Despite this, it might as well be forever as paying off student loans can take decades. Additionally, the benefits of a degree still do not justify the rise in student debt, as there are many issues within the Federal system of student loans.

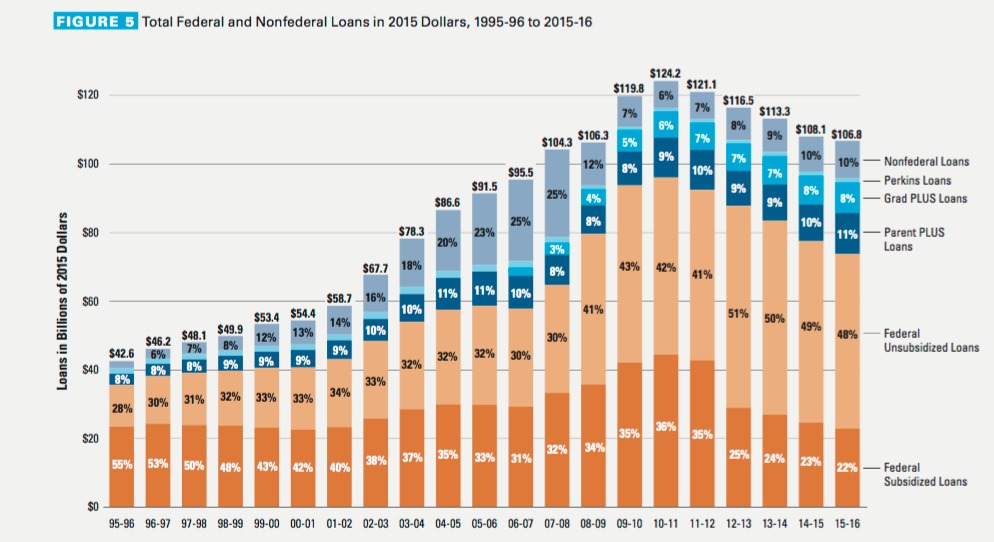

According to the “Student Loan Servicing” report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), student loan debt is up to $1.2 trillion (a decade ago it was $300 billion,) spread among 40 million borrowers, with an average debt of $30,000 per borrower. The annual report “Trends in Student Aid” by the College Board, revealed a 48% increase in loan borrowing from 2000-01 and 2005-06 (in inflation-adjusted dollars.) This increased to 65% by 2010-11. Although loan borrowing decreased by 23% from 2011-12 to 2015-16 student debt has only continued to increase.

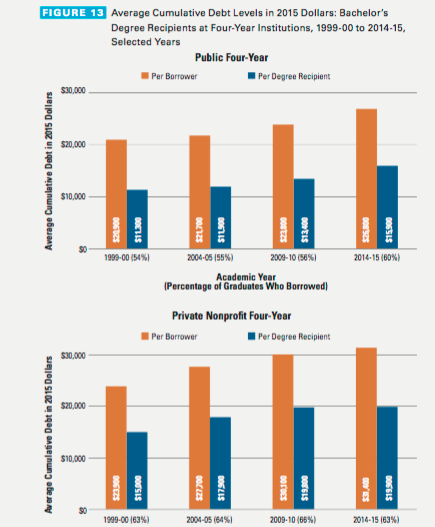

Looking at those who received their degree from a public four-year, the average debt level went from $11,300 in 1999-00 to $15,900 in 2014-15, a 40% increase overall. For a private four-year, the average debt went from 15,000 in 1999-00 to 19,900 in 2015-16, a 32% increase overall. Those who did not complete college had even higher debt averages.

To some, it is too soon to call the student loan debt issue a crisis. The White House study acknowledges there are changes to be made, but public concern should be low. Additionally, economists such as Joel Elvery from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland agree with this. According to the CFPB, the average monthly payment for those in the 20 to 30-year-old range is $351. Despite statistics like this, Elvery believes that post-grad earnings and repayment options offset these charges.

So how did we get here? Why has this happened? I will do my best to answer these pressing questions. However, the most important question is why should you care? If everyone eventually pays back his or her student loans, how does this affect the economy?

The Economy

If you take a step back and look at the big picture student loan debt affects everything in one way or another. Consumer spending and the housing market are the main concerns. Barbara O’Neill, a specialist in financial resource management for Rutgers University, believes student loan debt has slowed down the economy. As student loan payments become a priority, major life decisions (aka the ones that cost you the most) such as purchasing a car, and buying a home are put off for longer spans of time. Living to witness the entire U.S. financial system collapse does not help one’s views on financial well-being. If people doubt their financial ability, it is only logical that frugality will be the result.

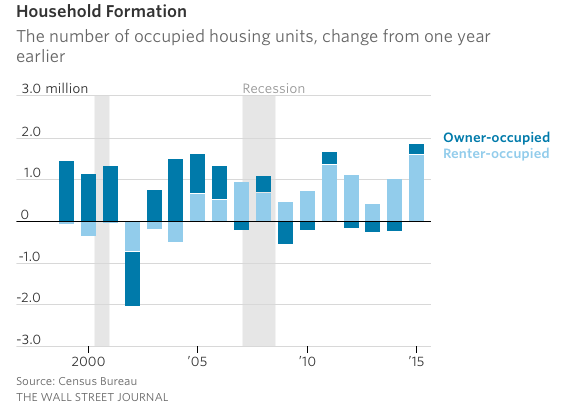

The Census Bureau revealed that the housing market has dramatically shifted from owner-occupied to renter-occupied, which is mostly thanks to millennial’s (the most recent college graduates.)

When looking at homeownership trends, the Federal Reserve found that fewer 30-year-olds have bought homes since the recession. Millennial’s join the work-force, wages rise, but purchases of single-family homes were down 6.0% in May according to the Commerce Department. Although this rose in September by 3.2%, the combination of high housing demand and low supply (you can only build so many homes) has increased housing prices.

One of the largest investments Americans will make in their lifetime is the mortgage. Mortgages are an important part of our GDP, and if purchasing of mortgages continues to decrease, there are consequences. For example, those who are currently trying to sell their homes are forced to sell below value, or worse off, not sell at all. We can’t blame millennial’s and their student debt entirely for issues in the housing market. Nonetheless, there is no denying that millennials are the future of our economy, and their halt in spending will have long-term negative effects.

Another concern is the fact that not everyone pays back student loans. In 2015, The Federal Reserve Bank of New York performed an analysis on repayment. They found that only 37% of borrowers were actively making payments, and 17% were delinquent. From the pool of borrowers that were struggling, 70% were from lower income zip codes. However, 35% of people from higher income zip codes also struggled with repayment. Higher delinquency rates are associated with not finishing school, but default rates still exist for those who did complete school. The highest percent of people who default (35%) have loans for $5,000 or less. This just goes to show that everyone is struggling with student loan debt in some shape, way, or form. It’s not fair to blame the borrowers entirely when all they wanted was the opportunity to get an education. Allowing more access to student loans was a good idea overall, but it is time we face the reality that the government may have been too generous.

The Screwed Up System

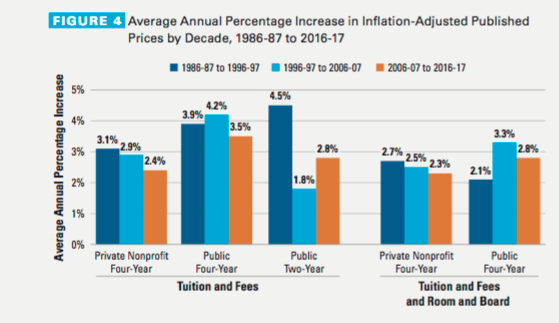

The main problem with student loan debt is that as tuition prices rise, a number of loans distributed must rise too. It is a continuous, vicious cycle. Private universities who have strong financial aid programs claim the right to have high tuition prices to make up for the deficit of those covered by aid. The problem is no better in public universities. Back in the 1970’s, public four-year institutions were the cheapest alternative. Although they are still cheaper than private universities, it is unknown how long it can stay this way. According to the College Board’s “Trends in College Pricing” from 1986-87 to 1996-97 there was a 3.9% average annual increase in tuition; from 1996-97 to 2006-07 there was a 4.2% increase, and by 2016-17 a 3.5% increase. As you can see, this is a pretty steady increase per year. Today, tuition plus room and board at a public four-year costs around $20,000, when it was closer to $10,000 in 1996.

One of the reasons for this is the decrease in state funding. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the average state is spending 18% less per student post-recession. The worst part is that these tuition spikes only make up for the deficit due to less state funding. The opportunities for students are not as plentiful as they could be when faculty must be fired to make a tight budget work.

A more obvious reason for tuition increase is economics 101: supply and demand. As more people enroll in college, the demand goes up. Despite there being plenty of colleges for every American, the supply or availability of spots at high ranking universities decreases. Colleges love to see how much they can charge before demand goes down. So far, we have all given into this experiment and paid the price. Additionally, the promise of a wonderful education from an affordable state school creates even more demand, but at some point, there must be cut-offs.

Finally, the main concern is the system itself. According to U.S. Department of Education, undergraduate students are allowed to defer loans if they have half-time enrollment in school, graduate school, face economic hardship, or a period of unemployment. Deferment is available for up to three years in most cases. Although this is a way to help students, some students use it as a way to put off loan payment for long periods of time. The current interest rate for direct loans is 3.76%. However, if the average borrower has $30,000 in undergraduate loans, $40,000+ in graduate loans, and interest, this can lead to repayment issues. Perhaps not default in every case, but it only takes a few late payments to hurt your credit score. If your credit score drops, eligibility for other loans such as for cars and mortgages are negatively affected.

Thankfully, there are precautionary measures that exist. The Obama Student Loan Forgiveness program provides many solutions for loan repayment. This includes income-based payments and interest rate reductions. Better yet, loans can be forgiven after 20 years if enrolled in the corresponding payment plan Pay As You Earn. Even with options of Pay As You Earn, the people in lower income regions are the ones who are still struggling with repayment. All these preventative measures will likely help, but it will take years to see the results. If tuition continues to rise at a steady rate, the need for student loans will increase ten-fold, and only so many steps can be taken to aid students in repayment.

There is no perfect solution, but ideally, putting tighter restrictions on loan availability and deferment could lower student loan debt. In addition, many borrowers are not fully aware of the binding loan contracts they are signing. If our high schools prioritized loan counseling as a part of college advisement, students may feel less inclined to borrow or make the effort to attend a more affordable university. Student loan debt is something that will most likely haunt us for decades to come, but hopefully, a decrease in student loan debt over time will jumpstart the economy. The economy may be doing well now, but the reality is the student loan debt crisis is a bubble waiting to burst. If we can decrease student loan debt, then the spending habits of young adults will also change and therefore increase long-term economic stability.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.