How does it feel like to live in China?

If someone asks different generations the same question, he would probably get completely different answers. Trade, a concept that only seems relevant to multinational corporations and business owners, has shaped almost every aspect of people’s life. The trade between the U.S. and China has grown exponentially in the past two decades, partly due to China’s economic integration into the global market and increasing needs and wants of Chinese consumers. In this blog post, I’m going to share a two family stories and shed some light on how trade has profoundly influence some Chinese families.

Military Factory, Xi’an, China 1954-2004

Prior to the Chinese economic reform in 1978, living standards has virtually remained at the same level for most of urban Chinese citizens.

When my grandparents moved to the city of Xi’an in 1958, they landed their first jobs as assembly worker and technician in a factory producing ordnance for Chinese military. Xi’an North Qinchuan Group, a state-owned military defense factory founded in 1954, was one of many military manufactures in the city at the time. Just like other state-owned industries such as oil, construction, telecommunication, and railways back in the 50s, getting a job in military industry is equivalent to getting a job for life. Responsible for testing parts that were ready to deliver and assemble for aircrafts, my grandparents worked at the same place for more than 30 years. In the late 70s, the factory was said to have more than 10,000 employees.

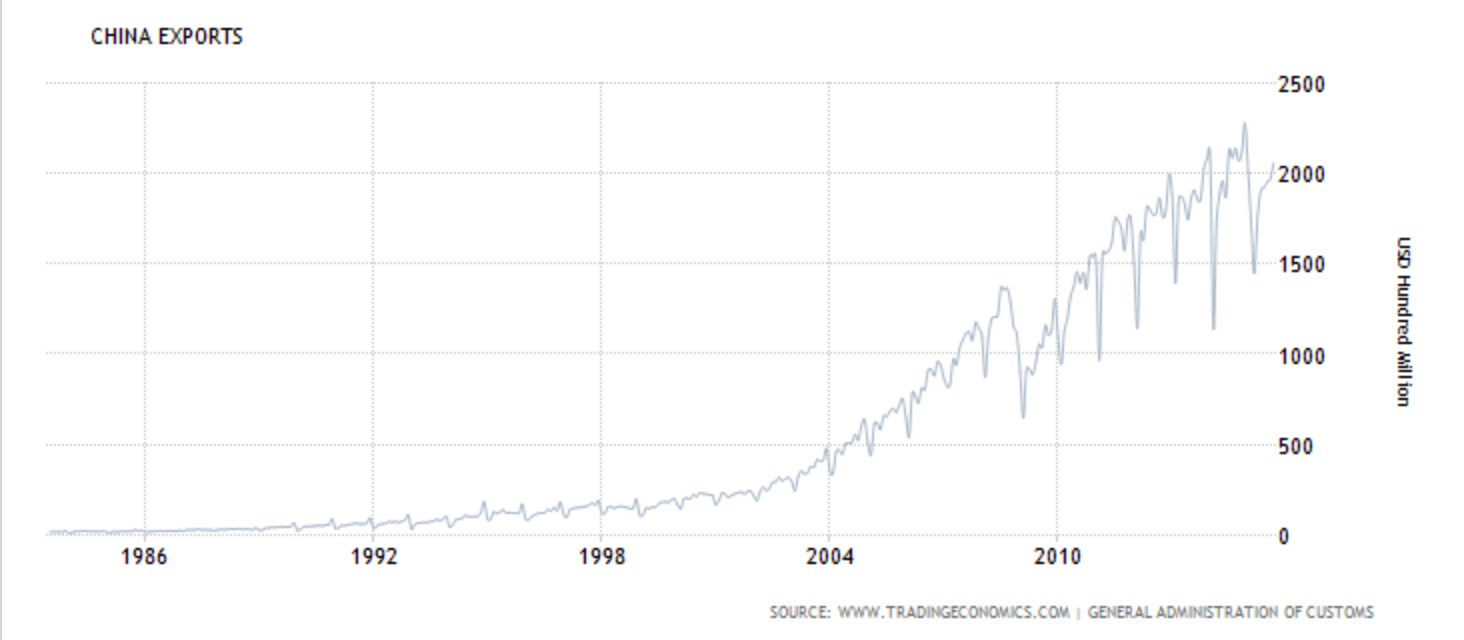

(Historical data of Chinese exports since 1986. Source: Tradingeconomics.com)

As China steered from planned economy to market economy, and opened its border to global trade, many state-owned enterprises suddenly found themselves obsolete and totally unable to compete with foreign companies. In the past twenty years, China has witnessed many traditional state-owned industries went to bankruptcy or protracted restructuring, and Qinchuan Group was no exception. In the late 1990s, the company attempted to switch its production from military defense to car parts. Unfortunately, as a state-owned company for almost half a century, its economy car model Flyer was in no way as competitive as cars manufactured in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. It filed for bankruptcy in 2004 eventually, and was incapable of paying pensions from time to time.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the total trade volume of goods in China, including both imports and exports, skyrocketed to 2.97 trillion U.S. dollars in 2010 from 20.6 billion dollars in 1978. Opening up the border line to international trade came with a cost. Internally, outdated industries would face fierce competition from the global market and lose its domestic market share. At the same time, domestic goods and services industries would have to upgrade and renovate itself in order to export their products to foreign countries.

Baby Formula, Shenzhen, China 1993

When the 2008 Chinese milk scandal made global headlines, foreign-made baby formulas were almost sold out overnight in China. Some even started panic buying in Hong Kong and subsequently caused intense friction between Hong Kong residents and mainlanders. But my father told me it was nothing new to him. When Wyeth, Mead Johnson and Abbott, all American infant formula manufacturers, entered mainland China in 1986, 1993, and 1996 respectively, they probably had never imagined how popular and desirable their S-26 and Enfamil baby formulas became among Chinese parents.

Because the product was so highly priced and it came in shortage occasionally in the 90s, some parents (my father was one of them) would even buy contraband foreign baby formula from smugglers at the border of Hong Kong and Shenzhen, a city bordering Hong Kong. It seems ridiculous in retrospect, but at the time when American brands first made its way to the Chinese market, they meant quality and safety to many consumers. Even today, a 900-gram standard packet of infant formula that sells for 25 U.S. dollars outside China is priced at 50-70 dollars in China, simply because the demand far exceeds the supply. High quality baby milk has become a scarcity in mainland China. Distributors can basically set a price that is three times higher than its customs declaration price, and there are still parents lining up to buy the product.

(Smugglers of baby formula waited outside Shenzhen/Hong Kong checkpoint, 2013. Source: News.163.com)

There is no doubt that market penetration of foreign companies in China stroke a huge blow against domestic milk producers. They basically have driven local infant formula companies out of business. It was since when no one was confident enough to trust domestic milk that series of laws and regulations came into effect to regulate the industry. The success of foreign baby formula brands in China implicitly reflects the fact that trade can have a huge effect on the market composition of importing countries.

This week’s field trip to the Port of Los Angeles definitely impressed me with the visualization of data. By visualization I mean seeing how trades take place in person instead of just reading numbers from economic reports. In fact, foreign trade is never something that is far away from our daily life. It’s what you eat on your lunch tables, what you see on the shelves of supermarkets, or even what you feel when you lose your jobs.