On Valentine’s Day, groups of Chinese young people waited for a Chinese movie, “Beijing Love Story,” at the Monterey Park AMC Theater. The movie was released day-and-date with China. The film made a strong opening weekend in North America, earning $128,000 from a limited release in nine screens over its first three days in the market following a Valentine’s Day premiere. Moreover, the film set a single-day record for a 2D film in China, with16.1 million Yuan.

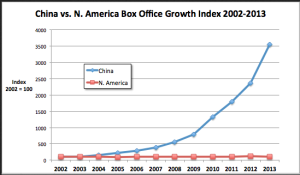

“It’s a golden age of the China film market now. It is experiencing a prosperous development…China’s local movies beat Hollywood movies and now have begun to lead the market in the past few years…I remembered that 60% revenues are from our local movies, which could not be imagined in the past,” said Long Wan, founder of Fire Rock Global Media. Wan is doing pre-production as the supervisor producer for a US-China co-production film, which is going to be filmed in Las Vegas this summer.

“Beijing Love Story” is only one of the “miracles” made in February, the Chinese New Year month. Another blockbuster, “The Monkey King,” has earned 1.02 billion Yuan since it was released, making it the third movie of One Billion Club in Mainland China. According to box-office records from Huxiu technology blog, China’s February box-office revenues hit 2.96 billion Yuan (about 50 million US dollars). Experts predicted that the number would probably hit 30 billion Yuan at the end of 2014. It is a dramatic change, comparing to 2007, that the market earned about three billion for the annual box-office revenue.

The second largest film market

According to a report from the Motion Picture Association of America in March, China overtook Japan to become the second-largest film market after the United States, with box-office receipts of around 17 billion Yuan (about 2.8 billion dollars) compared to 2.4 billion in Japan.

More than 5,000 new cinema screens were added last year, and a massive 903 new complexes were opened. The State General Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (a national media censorship bureau) reported that China now has 4,582 cinema complexes and 18,195 screens, an increase of 25 percent and 39 percent respectively from 10 year ago, according to Variety.

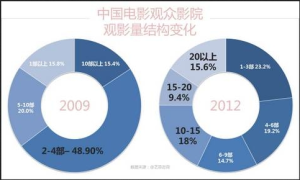

In the past five years, more Chinese audience chose to spend time with friends and families in cinemas. Below the chart shows that 48.9 percent of audience who buy film tickets watched two to four films in 2009, but in 2012, the number of films has been diversity showing that 15.6 percent of audience watched more than 20 movies yearly.

The high price of movie tickets hasn’t dampened the public’s enthusiasm for cinema. In Shanghai, an ordinary movie ticket costs 100 Yuan (around 15 dollars) and a 3D movie ticket costs 150 Yuan (around 25 dollars), according to Want China Time. China’s movie ticket prices are reportedly the most expensive in the world. However, the high price helped emerge a lot of ticket groupon websites that were very popular with Chinese young generations.

The development of film marketing strategy companies also contributed to the prosperous market. “Do you know the average age of our audience is 22….do you understand those young people born in 90s?” Wei Liang said to the Chinese director veterans in an interview. Liang’s film marketing company, Magilm Pictures, is one of the pioneers marketing companies in China. “When I opened the company in 2009, there were only one or two big-budget productions seeking for professional marketing proposals….now tens of movies every year,” As the chart shows that 37.3 percent of audiences are 20-29 years old, according to Entgroup.

China’s cultural market & Propaganda

China has a long history of propaganda in both news media and cultural market. In 1942, Chairman Mao Zedong gave a speech in a cultural panel meeting in Yan’an, which emphasized that literature and art should serve workers, peasants, soldiers and proletariat. And movies are the tools of propaganda for educating people about the “right things,” and also have to express the right political views. At that time, the Chinese film market experienced a downturn.

During the Cultural Revolution, the film industry was severely restricted. Most of older films were banned, only a few new ones were produced. The most notable ballet version of the revolutionary opera was “The Red Detachment of Women” (1971). Film production revived after 1972 under the strict jurisdiction of the Gang of Four until 1976, when they were overthrown. The few films that were produced during this period, such as 1975′s “Breaking with Old Ideas,” were highly regulated in terms of plot and characterization, according to “Uncovering Chinese films”, a book talking about films during China’s Cultural Revolution.

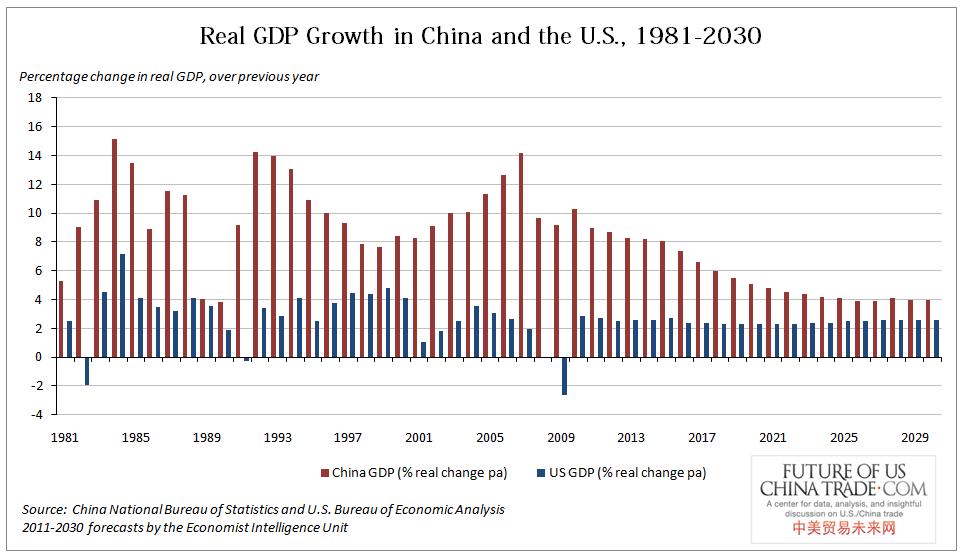

China’s economic reform and opening in 1979 gave a new life to the whole country as well as its movie market. The government film distribution reform project, which was released the same year, said that film distribution companies could keep 80 percent for developing new projects and pay 20 percent of film revenues to central government. The film industry flourished for a short time as a medium of popular entertainment after the reform project. Around 29 billion people went into cinema in 1979, according to historical record.

In 1993, Chinese government released a new reform report to open doors for private film companies to produce movies. The newly formed SARFT, State’s Administration Radio, Film and Television strengthened supervision over production at the same time. DMG Entertainment, a Chinese-based private film production and distribution company was opened in 1993, which produced “The Founding of a Republic” produced, a new style of mainstream Chinese films in 2009.

Foreign films restrictions & Co-production

Since 1994, China set up an import quota system and started to import ten Hollywood movies every year. “China places a strong emphasis on censorship not only to ensure compliance with the political aims, but also because the country lacks a rating system. The SARFT censorship board regulates the content of movies to make them suitable for the entire national audience,” according to a research paper from Duke University. The board consists of 40 members, including government officials, filmmakers, academics, and representatives from interest groups. The Hollywood films, which apply for a quota slot, must submit either a script or a finished film to the board.

Each Hollywood studio expects to get four to six studio films each per year into China through the revenue-sharing quota system that expanded from 20 per year in 2011 to 34 in early 2012. The expanded total includes an additional 14 Imax and special category movies, according to Variety. Because of strict policies of the quota system, a lot of Hollywood moviemakers figured out another way to enter China film market. One of them is co-production.

“Every week, there is at least one Hollywood producer asks me if there is any good co-production projects in China…They are eager to producing co-production films with China,” said Wan.

“It’s actually really hard to tell one movie produced by one specific country…there are co-productions all over the world,” said Bo Guan, international selection committee member of FIRST International Film Festival.

The main point of co-production films is that they have the same right to share revenues with cinemas as local movies, around 43 percent of revenues, but imported quota films only share 25 percent.

“They want Chinese culture to spread around the world so that they are known and have influence. So we look at the problem from the macro level to figure out what we need to do so that all our partners—U.S. and Chinese—feel like their needs are being met,” Dan Mintz said to The Hollywood Reporter, CEO of DMG Entertainment Company.

“The Growing Pains”

Expansion was the key word of China’s economic development in the past years as well as film market. “Hot money”, which represents excessive money from different fields flowing into film industry, played roles in movie production industry. Lots of non-professional enterprises such as coal companies, which hold “hot money”, entered into film market accelerating the high-speed development. Moreover, genre films that became popular in the market, like fast-food movies, fan movies and young idol movies, which lack deep cultural elements attract most young audiences. At the same time, more Chinese audiences are used to watching films in cinemas recent years, which became another advantage for China film market. However, it’s still not a real mature “battlefield” for moviemakers who really appreciate the art of film. The blockbuster “The Man from Macau” earned not only more than 500 millions box-office revenues but also a bunch of bad reviews.

Where is the future?

Economic austerity is the policy that China released for the new planning years in 2013. People might save their money in banks rather than paying for high-price movie tickets. And also there might be fewer businessmen investing in films, which are more risky than other industries. It is hard to predict if there is any influence on Chinese film market in the future.

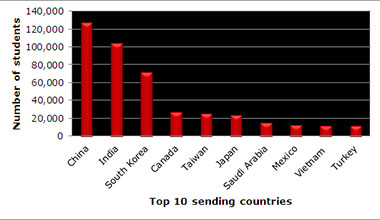

More Chinese students are choosing study film production or film related majors in US and they might be the main power of China’s new generation filmmakers. According to UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, there are 65 Asian American students, which comprised of 13% of the TFT population.

“As I know, USC has more than 20 Chinese student in film school…UCLA and AFI both have less than 10,” said Ivy Yang, a recent graduate from film school in Los Angeles.

Yang is pursuing communication management master degree in USC now. She appreciates the mature atmosphere of film production in Hollywood but she also wants to seek more opportunities in China even though normative rules of a mature film industry haven’t been set up yet there.

“ No rule is the best rule. It’s easier for young filmmakers to get chances…I just want to have a try,” said Yang.

Graduated from USC film school in 2013, Alan Wang has spent almost one year in Beijing as a music video director. His plan is to become a famous MV director in China and then seek opportunities for long feature films.

Graduated from USC film school in 2013, Alan Wang has spent almost one year in Beijing as a music video director. His plan is to become a famous MV director in China and then seek opportunities for long feature films.

“ I enjoy working here in Beijing except the air… it’s not about “rule” issue, I think every new graduate will face the same problem. We had lots of freedom for creating and shooting whatever we like, but here you have boss and clients…most of time you only can contribute 70 percent of your own ideas…I will stay here for longer time and see,” said Wang.

Sarkis Ekmekian is a junior at USC majoring in communication. He’s taking four classes, is the show-runner for Speakers’

Sarkis Ekmekian is a junior at USC majoring in communication. He’s taking four classes, is the show-runner for Speakers’ As a result, there has been a significant decline in both the number of transfer applicants to four-year colleges and enrolment at community colleges in California. UCs received

As a result, there has been a significant decline in both the number of transfer applicants to four-year colleges and enrolment at community colleges in California. UCs received

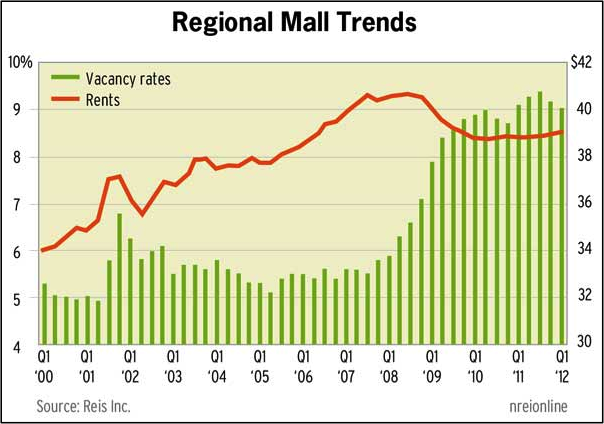

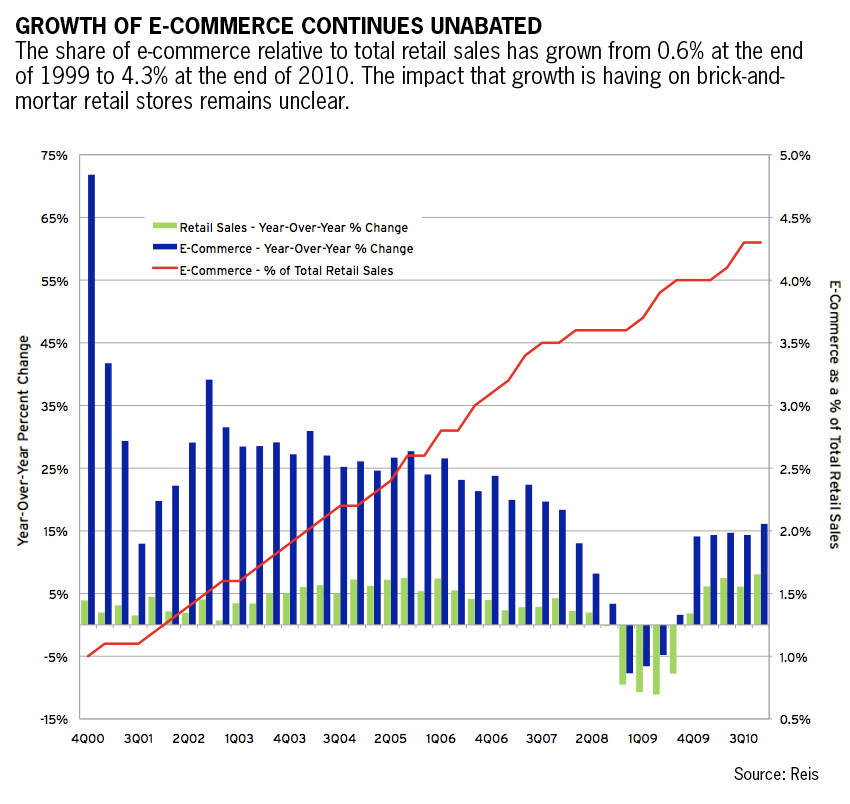

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.