It’s Complicated: on U.S.-China Film Industry Relationship

Yutai Han

(Image: ChinaFilmInsider.com)

With dazzling lights and glamour, the annual U.S.-China Film Summit kicked off yesterday in Los Angeles. Among the attendees are several leaders of the industry and Chinese directors, all working to achieve the same end: how to tap into the Chinese film market.

Admittedly, film is of the highest prestige of our society at large. It is the equivalent of Shakespeare in Victorian England, except that now the movie business is globalized and glamourized, serving human vanity and desires, and in turn the quality of films varies significantly. But generally speaking, the best films of the industry, produced by the highest caliber of crews and casts, and distributed by the savviest companies, attract audiences and money in a highly profitable way. A lot of them originates from Hollywood, a heavily industrialized dreamland of capital and talent from the very start, exporting formalized stories of dreams to the whole world. As a major trade surplus, cultural exports made up for 4 percent of the U.S. GDP.

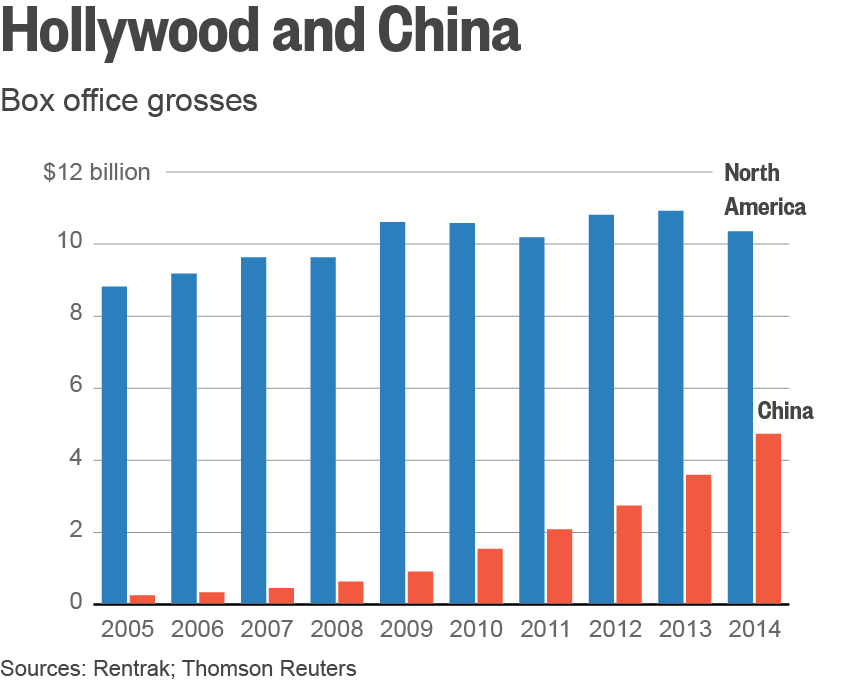

Similar to every economic story, the cards reshuffle when China becomes a player.

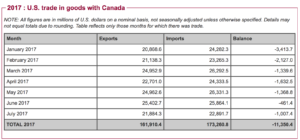

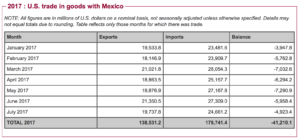

It was 1994 when mainland China opened its market to Hollywood with a quota of 10 films annually, which in effect led to a mass of people going to Hollywood blockbuster productions and a domestic revitalization. By 2020, the Chinese film market might surpass North America to be the world’s largest. It’s fair to say that now, the two biggest players in the film industry are the U.S. and China. Under the current deal set in 2012, China exhibits 34 overseas films per year. Some successful candidates are: Warcraft, a $47 million domestic box office and $213 million in China; A Dog’s Purpose, a $64 million domestic box office and $88 million in China. Note that these two productions had Chinese partners, and guess who—it’s Tencent and Alibaba! The promotion of Warcraft was wild. With the attention-grabbing subway poster and targeted mobile advertisement, and paid promotions among review channels, one literally cannot escape. This age of wide-spread and shameless marketing lays ground for propaganda films, such as the $848 million grossing Wolf Warrior 2, the biggest mega-blockbuster yet with a murky net of more than 20 producers and distributors that doesn’t fall short from CDOs.

The more alarming phenomenon is the nationalist and propagandist element of the film was able to fully manifest through the film medium and utilized by the film’s promotion people. The film was not necessarily propaganda but it was a chant of populist heroism, which could be utilized as propaganda. One outspoken critic received death threats. Films, as Slovenian Marxist philosopher Slavoj Zizek puts it, are “ideology at its purest”. It seems to me that it’s unlikely that Hollywood can march further into the Chinese film market, because under the obvious clash of interests, there exists an ideological tension. Even domestically produced Film or TV shows can be called off at the last minute, as one film, Feng Xiaogang’s Youth, was unfortunately delayed due to sensitive topics of Vietnam veterans being depicted as homeless. Other than that, the film is a personal project for the director to recount his most glamorous days as a young artist embedded within the military. Inside sources say that the market is not regulated by the Administration alone, but by some senior members who have the power to shut down speech. From now on, the future is downward. After Wolf Warrier 2, Chinese production companies convinced themselves that the most profitable way to make films is to make such films that “coincidentally” go along with the party’s authoritarian control. The stagnating Chinese film market can be partly attributed to this mentality. But on the other hand, films can also not be about promoting any ideology, but about love, loneliness, memories, the future and the universal human condition. Think Hong Kong cinema master of romance, Wong Kar-wai. His films sold good enough and especially among the Pan-Asian market to receive a Cannes. It is therefore not fair to regard the Chinese film market as impenetrable, and Chinese companies as corporate minions. If Hollywood and the liberal politicians try hard enough to look at China’s issues, that is. We need to restore cinema as “art manifest”. The road is long and bumpy, but we shall soldier on.