Text version below.

Text version:

I could go a whole week without touching a piece of physical currency once. Apple Pay at Starbucks, credit card at the bookstore, debit card at their favorite food truck, Venmo to split restaurants checks with friends, cash a check on an app, you name it and it can be done from a smartphone.

In today’s digital age, it’s easy to envision a day when grubby green dollars are a relic of a bygone era, like typewriters or pagers, but the evidence points in another direction.

There are two main reasons why the United States will keep printing the Benjamins for many years to come. The first is that most Americans still use cash as a secure way to complete transactions, especially for small payments. Secondly, many developing nations prefer to use American currency instead of their local currency.

In a 2015 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, credit card, debit card, and electronic payment methods were used in 58 percent of transactions. Credit cards accounted for 21 percent, debit cards for 27 percent and electronic for 11 percent of the year’s ways to pay among American consumers. In spite of widespread use of more modern payment methods, cash has maintained its status as the most used payment instrument at 32 percent of all transactions.

American transactions by payment type in 2012 and 2015. Over three years, cash use declined but remains the most used payment method.

While cash remains king for now, it’s popularity declined in the United States from 2012 to 2015 accompanied by in increase in the use of cards and electronic payments. Credit cards, in particular, increased use by 4 percentage points over the three-year period.

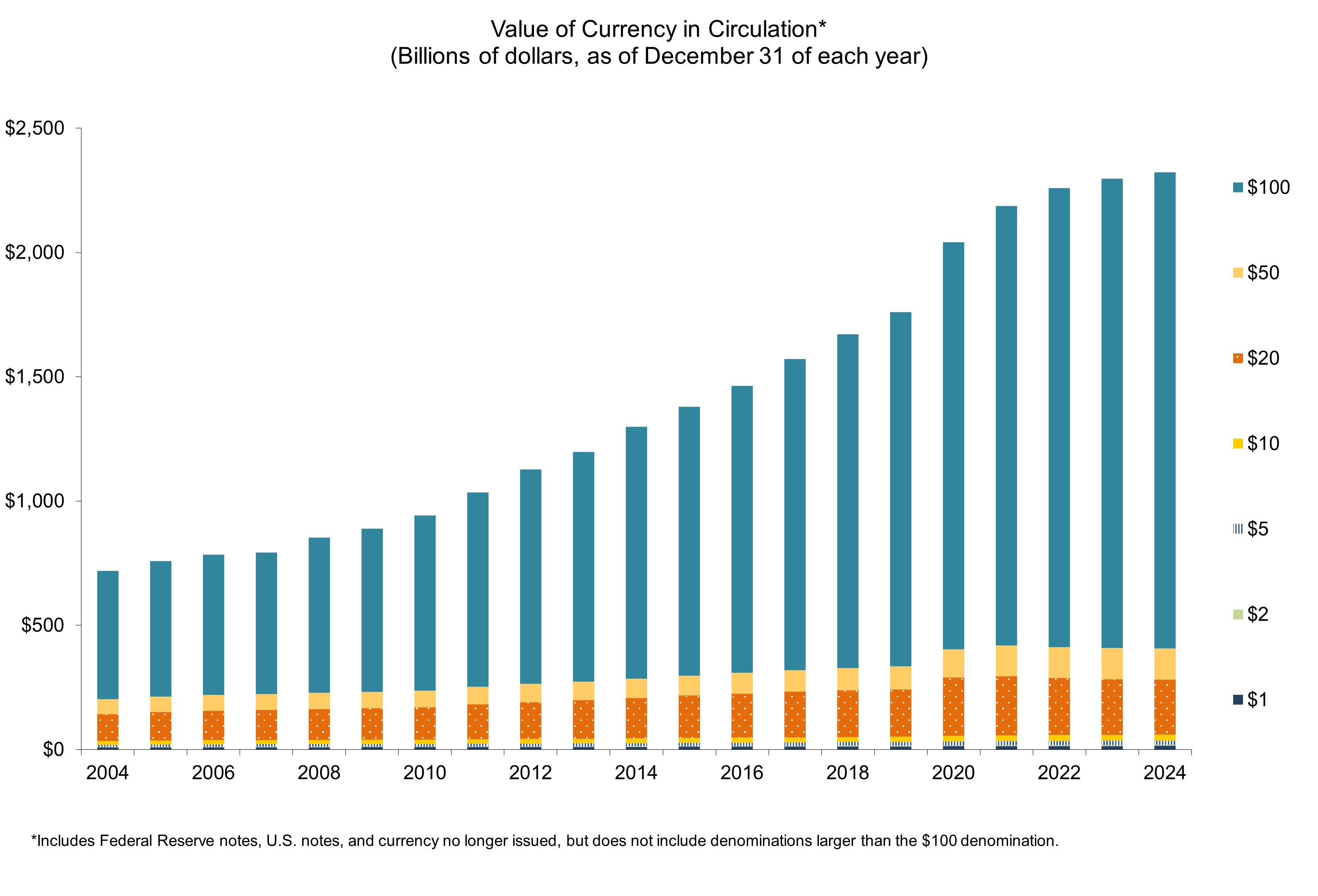

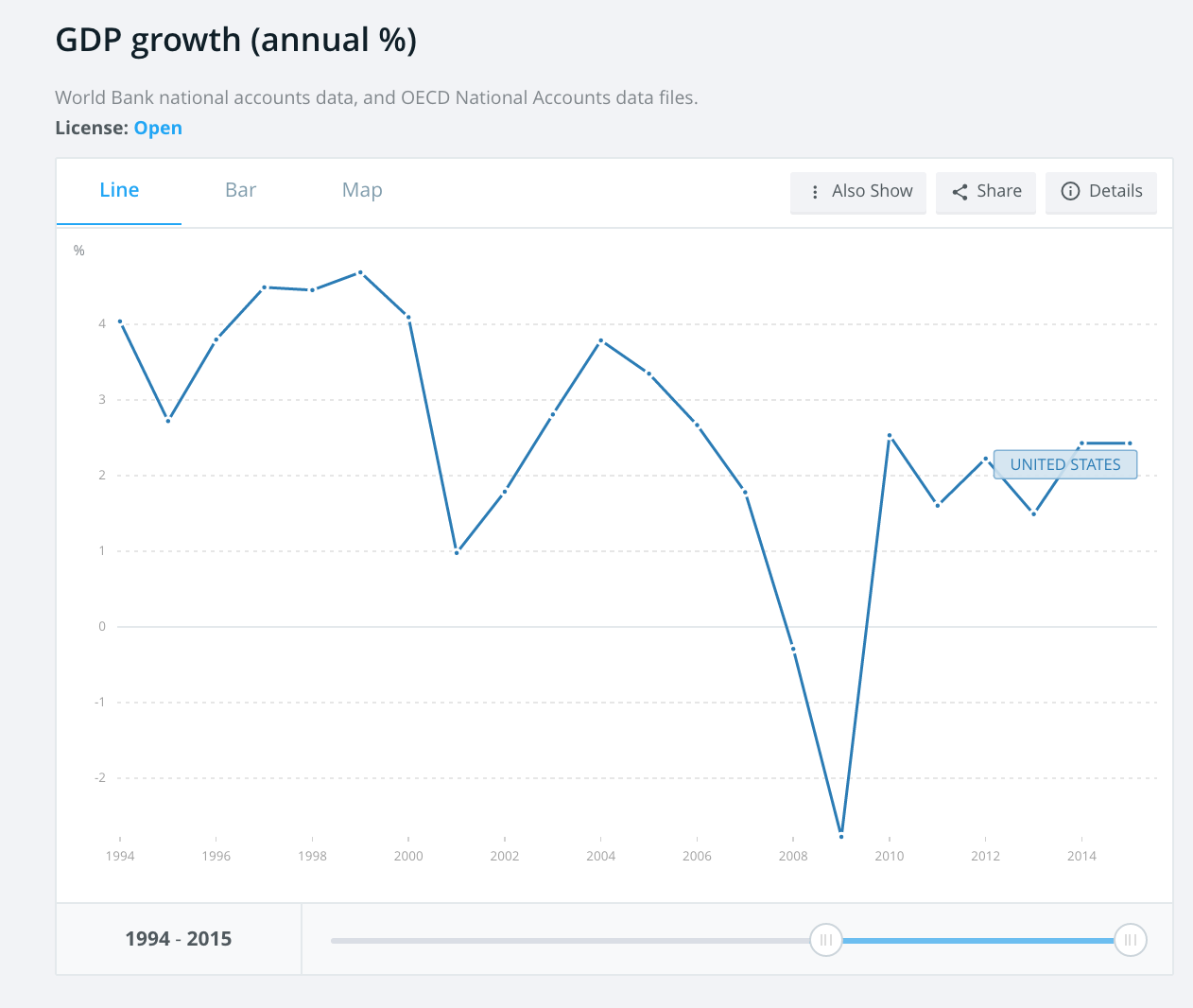

Despite declines in cash usage among Americans since 2012, the total Currency in Circulation Value has been rising every year since it was recorded and published by the U.S. Department of Printing and Engraving in 1995. Since then, the value of currency in circulation has increased over 300 percent to $1.38 trillion.

The total value of currency in circulation has grown significantly since 2008.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury decides how much physical currency should be in circulation each year by considering how much currency was destroyed in the past year and the projected demand for currency, in its various denominations, for the upcoming year.

It’s not just a response to inflation that is driving up the amount of dollars in existence. The rate of growth of currency in circulation far exceeded the rate of inflation between 1995 and 2015, as determined by the Consumer Price Index. Adjusted for inflation, the $148 billion in circulated cash in 1995 would be equivalent to $230.17 billion in 2015 dollars, just 16 percent of the actual value in 2015.

Although since 1916 inflation rates have been somewhat erratic, since 1995 inflation has remained relatively steady.

If the supply of cash is ever-increasing at a rate much higher than that of inflation, demand must also be increasing, otherwise inflation would rise because too many dollars would begin to chase too few goods. Between low inflation rates, since 1995 inflation has averaged around 2 percent each year, and a decrease in demand for cash among Americans moving toward credit and debit cards, there must be a missing piece.

To find the missing piece to the puzzle, travel to Cambodia where locals shuffle crisp one dollar bills from hand to hand at a bustling floating market, Zimbabwe where farmers collect U.S. dollars from customers at the market, or Argentina where middle class citizens buy cars with American cash.

This is called dollarization. It describes the use of a foreign currency in a nation either formally, to replace its national currency, or informally, where individuals use a foreign currency alongside their official national one.

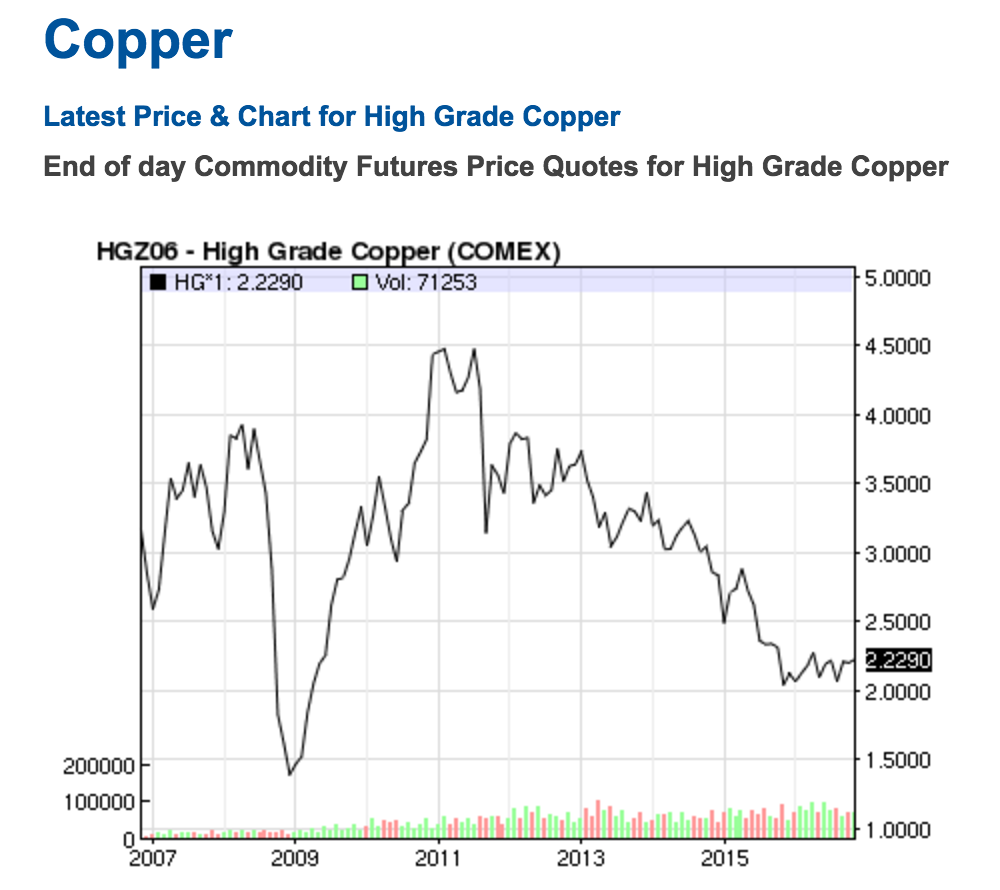

Dollarization in countries like Cambodia, Zimbabwe, and Argentina has led to increased demand on an international scale for American currency. For Cambodians, Zimbabweans and Argentinians alike, the dollar was and remains a safe currency that is stable unlike their native monetary system which has struggled and or continues to struggle with hyperinflation and political instability.

Research conducted by the Federal Reserve has consistently shown that overseas demand for American currency has been strong and will continue grow in the coming years. While there is not way to know exactly how much currency is abroad, estimates in 2011 suggested that about 50 percent of all currency in circulation was held outside of the United States, about $500 billion.

Nations that adopt the dollar as their currency formally, and to a lesser degree those that use the dollar informally, also face some disadvantages in exchange for stability, favorable interest rates, and increased trade opportunities. One of the major drawbacks of formal dollarization is the complete lack of control over monetary policy. Dollarized nations with stagnating or shrinking economies are unable to lower interest rates which would encourage consumer spending, investment and create growth.

All of this begs the question: where exactly does the Treasury belong in foreign nations’ economies?

The Treasury Act of 1789, created by the First Federal Congress, established the U.S. Department of the Treasury to manage government revenue collected mainly through taxes. Since its inception, the role and scope of the U.S. Department of the Treasury has expanded and shifted significantly. A part of government that once served almost exclusively as the American public wealth manager now also has major roles in foreign economic policy and even an office specializing in terrorism and finance intelligence.

The United States Department of the Treasury Building in Washington D.C.

Today, it is part of the Treasury’s stated mission to promote “the conditions that enable economic growth and stability at home and abroad” giving a reason for the Department’s support of international economies. Furthermore, providing unstable nations with a stable currency comes at a relatively low cost for the United States while creating some degree of political and economic leverage over the dollarized nation.

In 2015, the cost of printing the year’s currency was $578 million, 0.0001 percent of the year’s federal budget. In exchange for providing dollars, the United States has the ability to strengthen its influence over the nation in question. Additionally, use of the U.S. Dollar abroad facilitates trade by avoiding exchange rates and risks associated with dealing in unstable currencies.

A potential downside to allowing American currency to be used overseas is risking deflation as international demand increases without increases in supply. Luckily for the Treasury, it has the power to print essentially unlimited quantities of dollars in order to maintain the stability of the currency.

There is also no beneficial alternative. If the Treasury only prints what is needed for domestic use, international demand will remain constant with an even smaller supply of currency resulting in an increase in the value of the currency itself. This appreciation might also affect the overall value of the dollar but to a much smaller degree.

Today, the vast majority of money exists virtually in a computer network. The CIA World Factbook estimates that there at $11.78 trillion in virtual and physical U.S. dollars worldwide. This means that physical currency is only 9 percent of all American money in existance. As such, fluctuations in the value of this small portion can only affect the overall value of the dollar by so much.

So, providing currency to the world comes at relatively low cost to the United States and provides some political benefits but dollarization doesn’t entirely explain the increased production of $100 bills.

Currency production by the United States Department of Printing and Engraving separated by denomination. Production has increased overall, however, larger denominations have grown at a higher rate.

Hundred dollar bills in particular have become a larger proportion of the Treasury’s annual currency order. From 2010 to 2015, the amount of $100 bills ordered by the Treasury increased 34 percent from 7 billion to 10.8 billion notes. In the five previous years, from 2005 to 2010, $100 bill orders increased by only 18 percent.

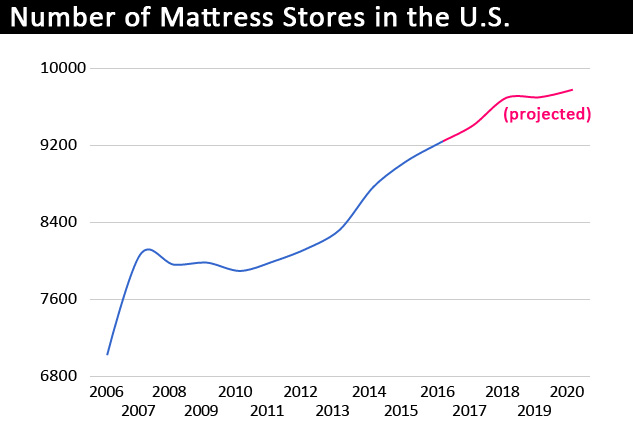

Yes, some people have converted their life savings into dollars and are hiding them in their mattresses as a safeguard against the instability of their own currencies. However, logically, most people who are doing this are in developing nations and won’t have vast amounts of savings to convert into dollars and stash away.

A study conducted by Peter Sands, a Professor at Harvard, suggests that a significant amount of American currency, particularly $100 bills, is preferred by and thus facilitating international crime. The study estimates that global crime finance amounts to over $2 trillion U.S. Dollars per year. Sands argues that most of the illegal transactions that combine to make this astronomical figure use cash due to its anonymity, lack of record, and ease of transportation. Given the large sums of money exchanging hands, large denominations of stable currencies issued in mass quantities are the preferred form of payment.

From this point of view, the Treasury can be seen as an organization that is unintentionally aiding international criminals. Upon further scrutiny, however, the Department can’t really be held accountable for how people use its bills. The Treasury would face opposition to decreasing the discretion and portability of cash because those same characteristics make it attractive for law-abiding citizens.

Perhaps the best it can do is limit the supply of large denominations as proposed by both Sands and former Secretary of the Treasury Lawrence H. Summers in order to limit its facilitation of crime.

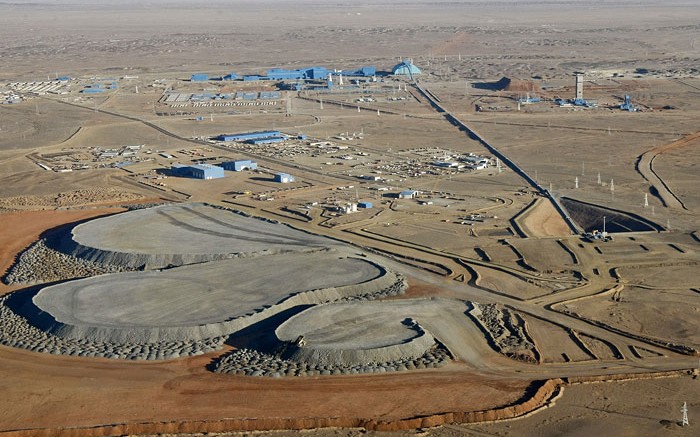

Former nomads settle in their gers near mines to find work.

Former nomads settle in their gers near mines to find work.