First time in its 102-year history, Hollywood tycoon Paramount has partnered with China Film Corporation, the country’s largest state-funded film group, to produce a movie about the legends of Marco Polo. The movie will mostly be shot in China, directed by Rob Cohen from Fast and Furious, with Chinese supporting characters speaking Mandarin on set.

First time in its 102-year history, Hollywood tycoon Paramount has partnered with China Film Corporation, the country’s largest state-funded film group, to produce a movie about the legends of Marco Polo. The movie will mostly be shot in China, directed by Rob Cohen from Fast and Furious, with Chinese supporting characters speaking Mandarin on set.

What Paramount has been involved now, is the U.S. – China co-production, which is officially recognised by the Chinese government. The co-production projects has been backed up by the Chinese government in the early 2000s, but really gained its popularity after 2011.

Nevertheless, Xiaotian Mao, who represented the Chinese government at the 2014 U.S.- China Film Summit held in Los Angeles, thought the co-production business was far from success.

“So far, I would say I haven’t noticed any successful U.S.- China co-production film,” Mao said in Chinese while giving a speech at the summit.

Despite the discouraged feedback from Chinese official, the ticket to the co-production is already hard to get. To gain the co-production status, films must be licensed by China’s media regulator, which sets rules on the film’s finances. The movie must have a fair amount of filming location in China, and a percentage of Chinese stars in the cast approved by the government. The government also has the right to rip off the co-production label anytime when they find the project is no longer qualified.

Under the tedious rules, the co-production still seems booming with more and more Hollywood studios and investment coming in. Paramount is the fifth oldest surviving film studio in the world, yet the latest newcomer to the co-production game.

“Sometimes I woke up in a cold sweat, picturing myself 20 years ago and asking: why would we do that?” said Mark Badagliacca, Paramount’s executive Vice President and CFO. Badgliacca has served the company for more than 30 years and recently just got back from China, where the details of this co-production project has been finalized. “But they (the Chinese filmmakers) are willing to learn from us and we also need the access to the Chinese market.”

The tricky land of profit

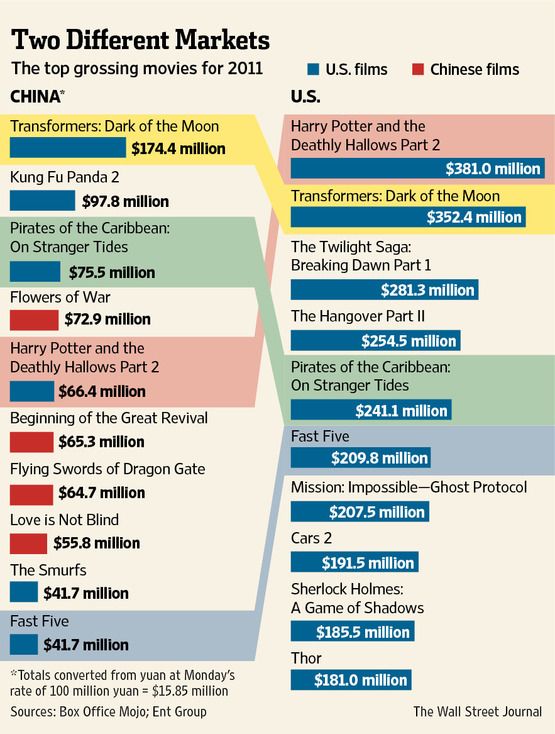

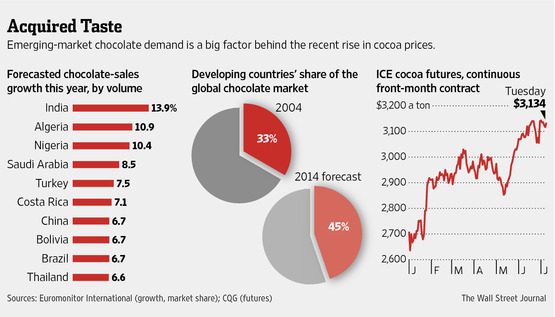

Hollywood may have found another treasure land more than six thousand miles away in China. It was only from January to November 2014 that 11 Hollywood movies have made to the top 20 China box office list, with a total accumulative record of RMB 7.9 billion ($1.28 billion U.S. dollars).

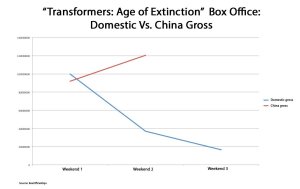

The latest movie from the Transformers franchises, Transformers: Age of Extinction, is the most successful Hollywood blockbuster in China this year. From its world premiere in Hong Kong, which was also a first for Hollywood, it has swept the China silver screen. The movie has topped both annual and opening week box office record in China. Despite its flat performance in north America, Transformers: Age of Extinction still became the 19th movie that has a billion dollar box office sales in the history. According to China’s film consultant Entgroup, over 30% of the ticket sales came from China.

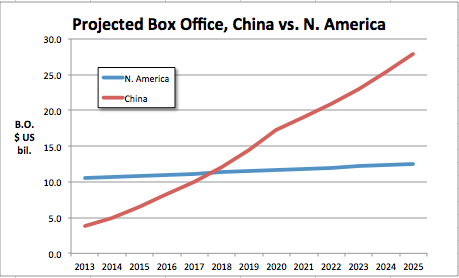

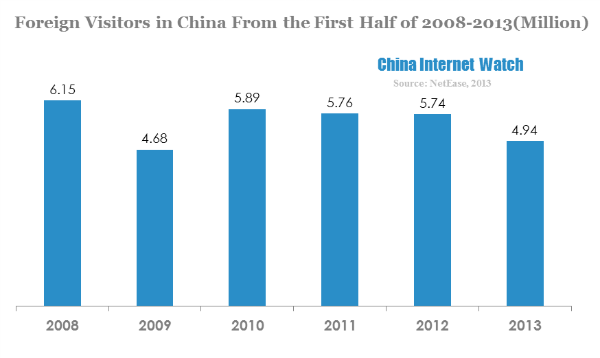

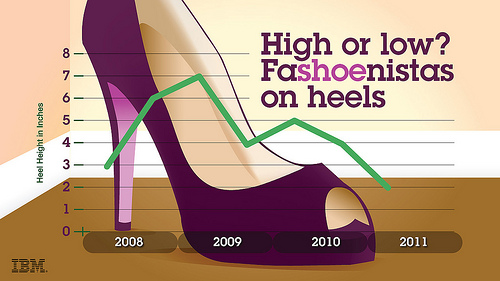

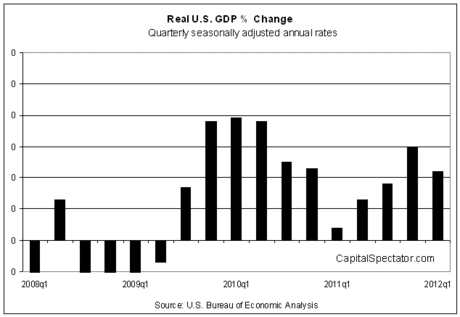

According to the statistics from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), the North America theatrical market has experienced nearly zero growth last decade. Meanwhile, China has become the world’s second largest movie market with a steady and rapid annual increase. In 2013, China’s box offices pulled in RMB 21.6 billion ($3.17 billion), a 27% increase from 2012. In China, there are 13 new cinemas opening in China each day according to MPAA, which in recent years has helped boost box office sales.

Still, China remains a tricky place for the Hollywood filmmakers to do business.

The success of Transformers: Age of Extinction is rare. A number of productions coming from Hollywood never made it to release in China, due to the government’s strict control. The government keeps a tight grip on foreign films that are shown in the country, requiring everything from preliminary script approval to sign off on the final cut. Foreign film releases are limited to 34 per year.

A path to the triple-win?

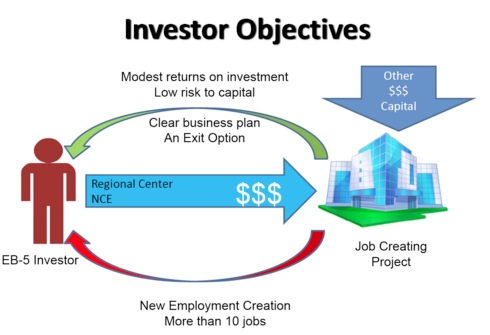

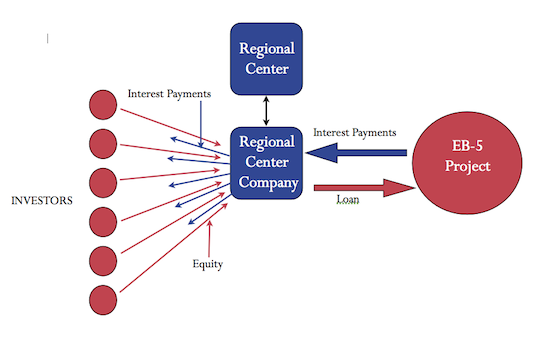

Despite how tedious the process of a co-production could be, the benefits, however, may be worth the pain. A co-production gets to keep 47 percent of box office receipts, while the imported films only get as little as 13.5 percent. Most importantly, the co-production doesn’t need to go through the release quota control set for the foreign movies by the Chinese government.

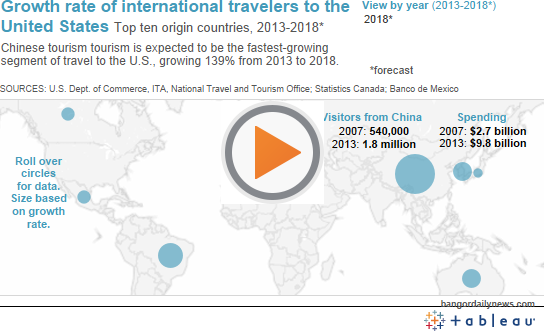

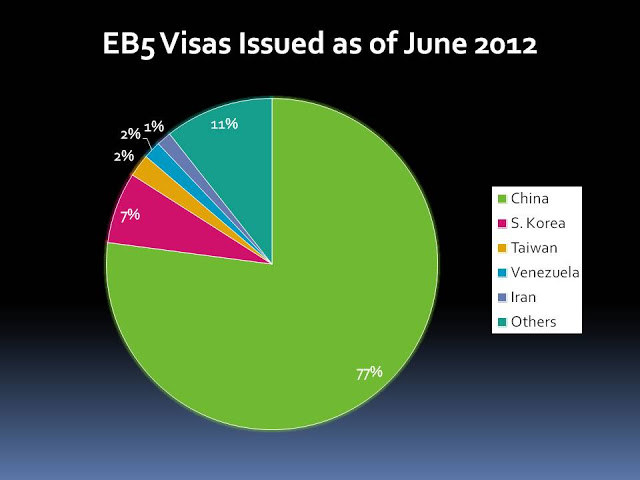

Chinese investors, on the other hand, have noticed the profit margin and eager to join the co-production game. Early 2014, Dalian Wanda Group said it is in talks to acquire a stake in Lions Gate Entertainment Corp. Alibaba Group’s Chairman Jack Ma paid a visit to Hollywood in October 2014, seeking alliances.

In recent years, Chinese government has vowed to grow the nation’s “soft power”. “The stories of China should be well told, voices of China well spread, and characteristics of China well explained”, said China’s President Xi Jinping in the 2014 new-year speech. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, scholars interpreted the new-year speech as a signal of political purpose for the government’s willingness to promote China’s culture and systems with Hollywood’s competence.

The propaganda mission of Chinese government, the eagerness of Hollywood studios to get access to the Chinese market, the desire of Chinese learning the Hollywood expertise in film and making profit… Co-production seems able to simultaneously work in line with all the agendas.

In 2014, there are more than 60 co-production applications sending to the media regulation department in China. But judging from the previous performance of co-production out in the real market, a strong possibility for disappointment remains.

The dilemma

The frequent box office failure of the U.S.- China co-production have brought the first wave of disappointment.

China’s web content provider Sina.com has put a collection of the co-production movies that bombed at the box office. Man of Tai Chi, which is Hollywood star Keanu Reeve’s directorial debut, ranked No.9 at the list. The movie made ¥ 27 million RMB ($4.3 million) in China and only $0.1 million in North America, leaving a huge loss of more than $ 20 million uncovered.

In the co-production business, some stories have utilized the benefits of the Chinese partner’s involvement with a story appealing to both the Chinese and North American audience, such as the Karate Kid (2010), made by Columbia Pictures and China Film Group in 2010, grossed $358 million in ticket sales worldwide. By contrast, the Chinese version of High School Musical, made by Huayi with Walt Disney the same year, earned less than $155,000. It is not an easy job to anticipate the audience’s preference and get the formula right.

“By far the biggest challenge for the co-production is finding the right story to tell,” said Robert Cain, who runs Chinafilmbiz.com and is a consultant to producers and others doing business in China. “Mostly they film stories that has been suitable for either the Chinese audience, or for the international audience, but not for both.”

Chinese authorities’ vague regulation has become another major challenge for the practice of co-production. There are no specific rules of the percentage for either the investment or the casting coming from China written in paper. The application may get approved smoothly; but the authorities can take the co-production title away in the milddle, or disapprove the final work after censorship and put the movie back to the “imported” category.

In response to the vague regulation, Hollywood blockbusters like Iron Man 3 chose to ignore the official co-production process. Instead of waiting in the line for co-production approval, “the film is challenging conventional wisdom about how best to tap China’s lucrative but tightly controlled film market”, quoted from the report by the Wall Street Journal.

“Generally speaking, the U.S.- China co-production is not a success,” said Stanley Rosen, political professor at University of Southern California specializing in Chinese politics and society. Rosen thinks there are two major reasons that lead to this failure; one is the tighter co-production policy from Chinese government; the other is that U.S. and China actually join the co-production with different purposes- China wants propaganda and experience, while Hollywood simply just wants to make profit.

A future of uncertainty

After years’ of development, the U.S.- China co-production has encountered with the bottleneck.

Robert Cain thinks it is possible to find better co-production story ideas through increasing the Chinese team’s film literacy and enhancing the quality of communication. After better stories ideas being made, the Chinese government censorship will become the next biggest obstacle on the way.

“If the censorship rules stay the same, it will be always hard to do co-productions,” said Cain. “The creative people in China don’t like the rules either. I think a government as strong don’t really need that kind of protection; but I don’t know if the censorship rules going to change in the future.”

Meanwhile, rumor goes on and off about the possible quota increase by the Chinese authorities to let more foreign productions in. China signed an agreement on its current quota system with the World Trade Organization in 2012, valid for five years. This means the second round of negotiations will start around Feb. 17, 2017.

It is uncertain for either the change for the co-production rules or an increase on the film import quota. The only thing people may know for sure, is that China has a huge film market with great potential.

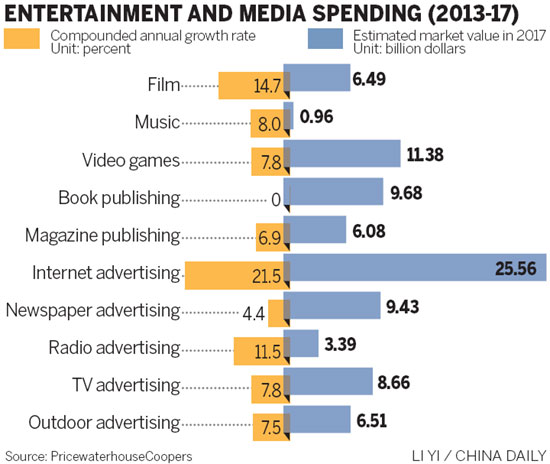

According to an Ernst & Young report on China’s media and entertainment industry in 2013, China, which now stands as the second-largest film market in the world after Japan, will surpass the U.S. and become the biggest film market by 2020.

Data retrieved from Ernst & Young

Facing China, the under-developed huge market with uncertainty, there are several options opening for the Hollywood filmmakers. It may be a good idea for the Hollywood studios to get a better understanding is role and keep involving in the co-production; it may also be a wise choice for the filmmakers to work with the storylines, avoiding sensitive elements, in order to get a bigger chance to release the works in China when the door opens up a little bit more.

For Paramount, the choice is doing whatever they can to get the access to the Chinese market, according to Mark Badagliacca.

“I think it is best for us to do everything we could; we are even going to make films in China for the Chinese audience only,” said Badagliacca. “China is a giant market; and it is something really have an impact on us.”