Troubled Waters

It’s 2007 and The Big Three automakers, Chrysler, General Motors and Ford, all found themselves in big trouble. They were on the verge of collapse, with wage bills spiraling out of control and foreign competition continuing to undercut their former domestic supremacy. GM’s profits were down 90% in the first quarter compared to the previous year, and the automakers looked for any means by which they could save themselves amidst the falling debris of debt, rising gas prices and cars no one wanted to buy anymore.

Most economists argue that globalization is a net positive for economic growth, benefits consumers in a number of ways and should be encouraged. It creates a more competitive environment that in theory increases not only the quality of products available to the average consumer while also decreasing their cost. The American auto market shows us a very clear example of how it works. The Japanese and Korean automakers entered the US market and essentially took the Detroit giants out at their knees. Companies like Honda and Toyota created cheaper, more efficient and longer lasting cars than their competition and won larges swathes of the market.

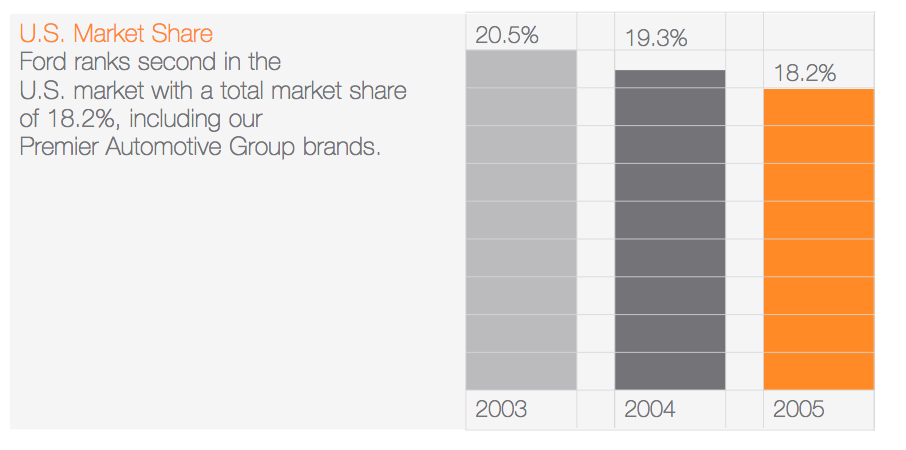

In response, American automakers cut costs fast and furiously. For example, in the mid-2000’s Ford downsized significant parts of the company by closing plants in order to reduce excess production and they liquidated thousands of salaried positions. According to it’s 2005 earnings statement, Ford planned to close 14 manufacturing plants by 2012, leaving some 25,000 to 30,000 workers jobless. They did this because they did not have a demand for the vehicles at level needed to operate the facilities at full capacity. In fact, they operated at a mere 75% of capacity as of that earnings release. These initiatives were a direct result of automotive sector of the company losing almost $3.895 billion in 2005. Eventually, Ford cut over 40,000 jobs between 2005 and 2008.

Ford’s 2005 earnings report shows trend of shrinking market share

Ford’s 2005 earnings report shows trend of shrinking market share

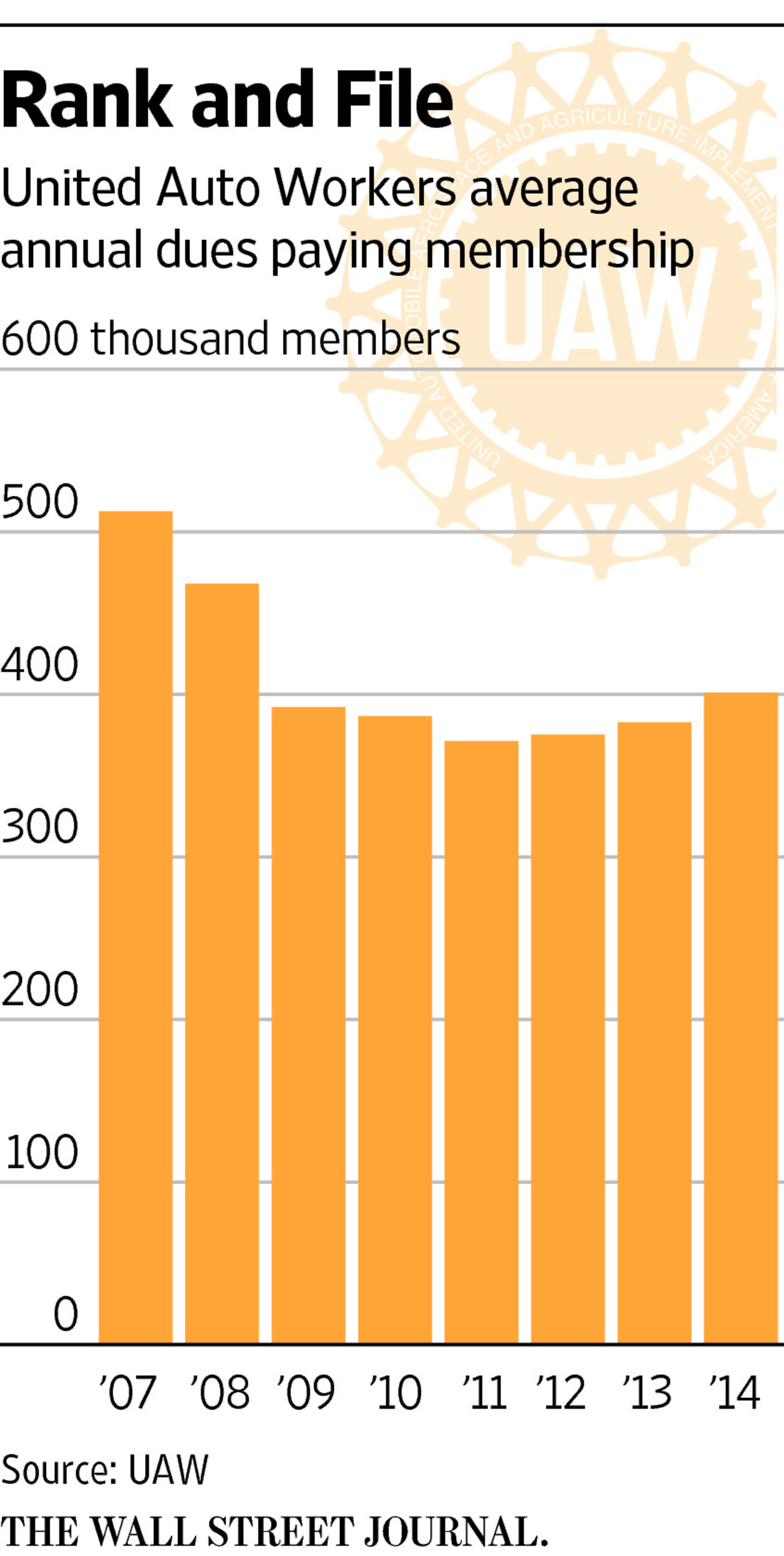

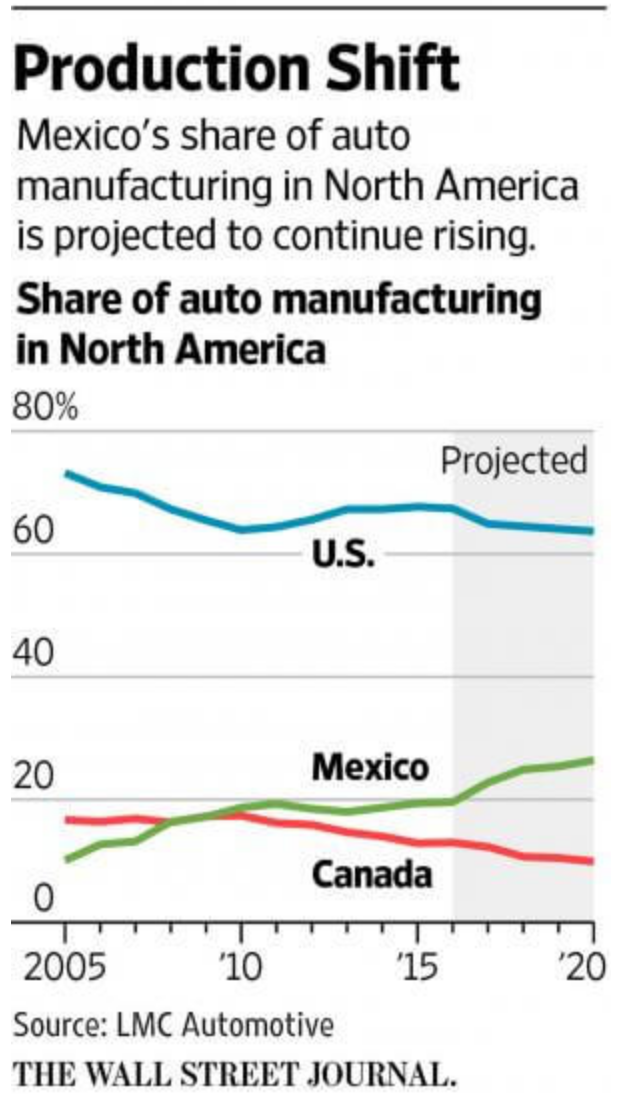

This poses a major drawback, for some, of globalization and how it effects workers; it depresses wages. This happens because workers are now faced with a market place flooded with cheaper competition. Logically, that should for the wages for American auto workers to decrease in order to compete with the foreign workers. But in this instance, the wages of the American auto worker have not shrunk to match the other entrants in the field. Author Edward McClelland points out in a Washington Post column that, “because it provides pensions and benefits that GM’s labor costs average $58 an hour, compared with $48 for Toyota and $38 for Volkswagen.” So the Big Three cut jobs, shut down factories and continued to move production into cheaper wage countries like Mexico. These moves cut union membership from 1.5 million in 1979 to 400,000 members as of 2015.

The Big Three and the weakened unions had to confront the wage issue in order to find a workable path moving forward. Faced with the loss of jobs due to reductions and outsourcing, the unions agreed to system in which hourly employees hired before 2007 would have the designation of tier one or “Traditional” employees and their wages would remain frozen, but not cut. Whereas, all new hires from 2007 onward would be deemed tier two employees, and their pay would be capped permanently, with no hope of ever matching the rates of tier-one employees. Basically, they imposed a wage ceiling of $19 an hour on newer hires, no matter how long they worked there, while the longer tenured employees could make up to $28 an hour. The move was justified as a means to save thousands of factory jobs in the U.S. A move that has been since in other companies such as Kroger’s supermarket chain and United Parcel Service. Many point to Ronald Reagan’s use of tiered wages against government employees at USPS in 1984, as the first instance of its use in the US. Now the automakers were betting on its efficacy as well.

The Bailout

Initially, the plan did not make a major impact. We know an enormous number of factors played into the demise of the Big Three. After all, if you look at the Ford’s stock over the past 15 years, we see a massive downward trend from 2000, far before the financial collapse, until it scraped the bottom of the barrel in 2008. Foreign competition battered the Big Three, and drastically reduced not only their market share. For a number of years, the Americans could still bank on consistent sales volume to maintain, but after the recession demand dried up producing the crippling blow. Now higher labor costs became an even more significant point of contention in explaining why they couldn’t keep up. Soon Chrysler and GM teetered on insolvency. Ford hung in, but could’ve easily tumbled as well.

Ford Stock Price 2000-2010 Source: Google Finance

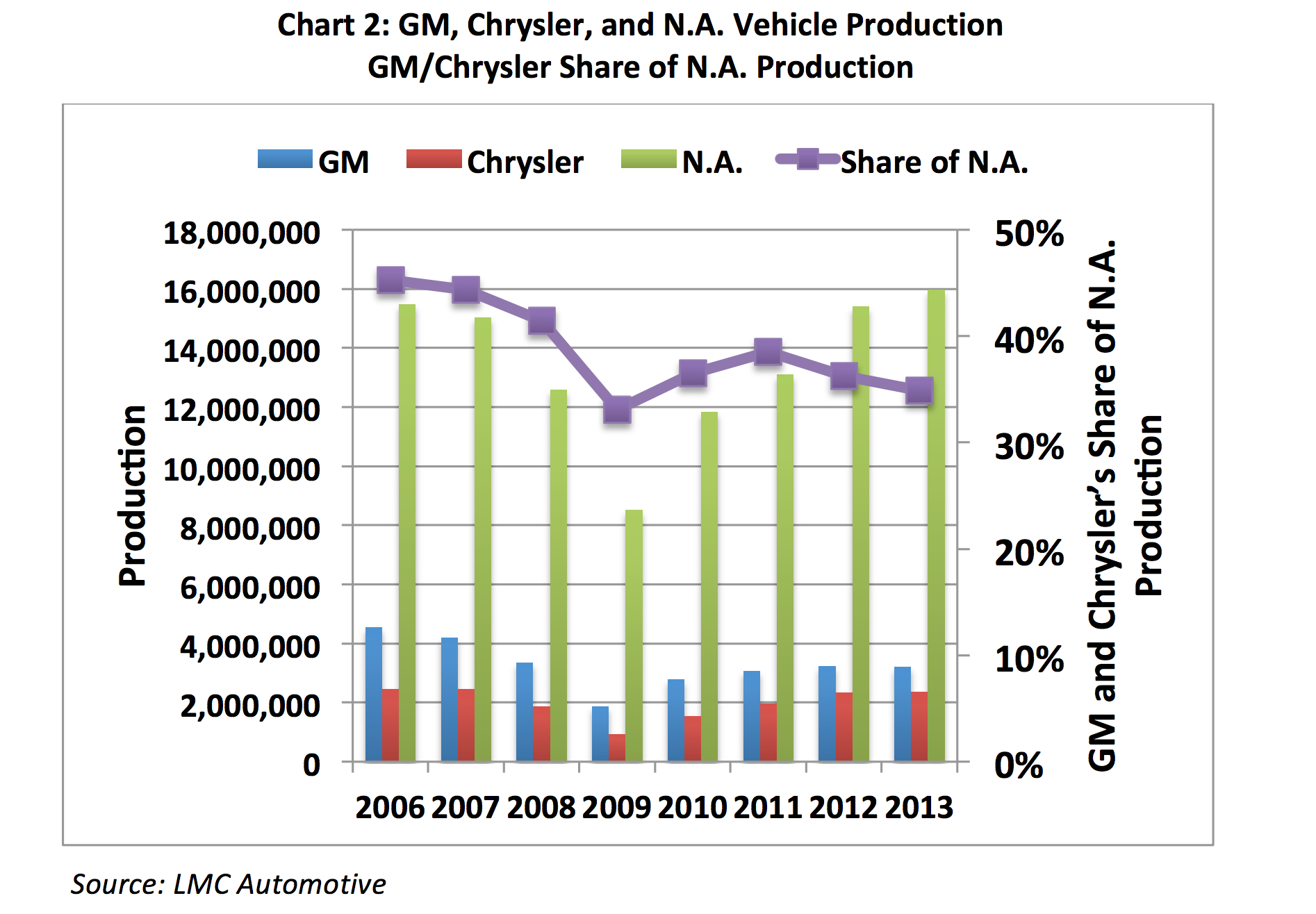

In late 2009, both Chrysler and GM filed for chapter 363 bankruptcy. In response, despite some calls to allow the companies to fail, the Obama administration intervened to prevent an, “Industrial Lehman Brothers Effect.” By utilizing TARP, the Troubled Asset Relief Program instituted under President Bush in 2008, the government dispersed $49.5 billion to GM, $17.17 billion to Ally Financial, the former financial arm of General Motors, and $11.96 billion to Chrysler in various loans, bankruptcy payments and share purchases. As a result of this agreement, Chrysler went under the dominion of Fiat, and the two companies merged to become Fiat Chrysler Automobiles US.

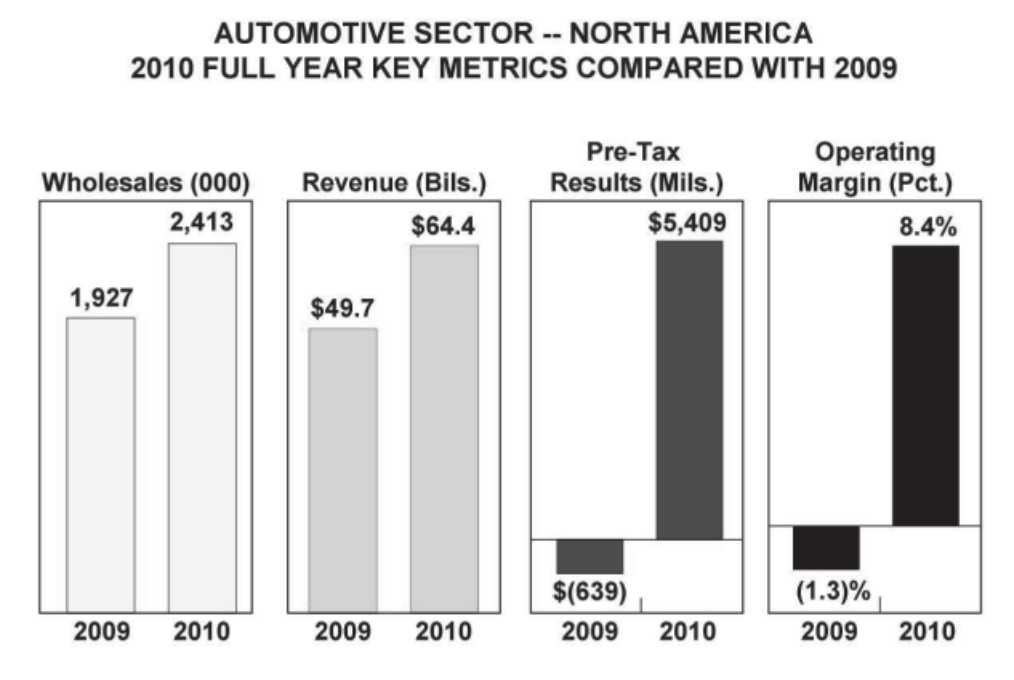

Ford, after initially taking part in conversations about a bailout, decided to walk away from the negotiations. It drew on lines of credit that they established in 2006 by mortgaging assets ad setting up long-term borrowing plans for the credit crisis in 2008. This allowed the company to infuse itself with life preserving liquidity to weather the storm of contraction in 2009 and 2010 which included; shrinking sales numbers and, consequently, shrinking production output.

These actions undoubtedly saved a number of jobs, and allowed the American auto industry to continue to exist as we know it. The Center for Automotive Research released a report on the topic in 2013, “Our results show the U.S. government saved or avoided the loss of $105.3 billion in transfer payments and the loss of personal and social insurance tax collections—or 768 percent of the net investment.” The report continues, “Additionally, 2.6 million jobs were saved in the U.S. economy in 2009 alone and $284.4 billion in personal income saved over 2009-2010.” But what did a lot of these “saved” jobs pay? A fair number of them didn’t pay what they used to, and that was the intention. But the results are difficult to argue against. Ford added more than 17,000 hourly jobs in the last five years through in-sourcing, and brought back production of certain pickup truck models from Mexico. Meanwhile FCA brought in around 15,000 new workers since their bankruptcy 2009.

Removing the Limiter

The US government attached a number of stringent restructuring requirements to the bailouts of Chrysler and GM. Initially, the tiered wage plan, as agreed to in the labor negotiations of 2007, prevented the Big Three from having any more than 20% of their work-force constituted by tier-two employees. After GM and FCA filed for chapter 363 bankruptcy in 2009, Obama lifted that restriction. The cap was supposed to be reinstituted during labor negotiations in 2011, when the companies became profitable again, but that did not happen and the tiered wage agreement continued. According to the New Labor Forum, FCA’s workforce consisted of up to 45% tier-two employees before the most recent collective bargaining sessions in 2015, while Ford’s number sat at 29% and GM at 20%. As a consequence of having the most tier two workers, FCA saw the greatest benefits to this plan. It saw wages drop to an average of $48 dollars an hour, according to the Center for Automotive Research, as compared to Ford whose costs rested at $57 an hour.

But Ford still pointed to the new agreement as a key factor in their regaining international competitiveness. From its 2011 earnings report, “In 2011 we signed a four-year agreement with the United Auto Workers that will help us improve our global competitiveness. As a result, we will be investing $16 billion in the U.S. and adding new jobs at our U.S. manufacturing facilities.” They also reported an increase of pre-tax operating profit for their North American operations to $6.2 billion. A massive change from the losses they faced back in 2005. Obviously, many factors play into that resurgence, but wage cost reductions were a major talking point for all of American auto makers.

Source: Ford’s 2011 end of year earnings report

Source: Ford’s 2011 end of year earnings report

The Downside of Tiered Wages

While the new wage structures helped retain many jobs, and played a role in the revitalization of auto industry in the US, sometimes things resonate on a deeper level than just spreadsheets. The wage gaps between employees, with no possibility of ever closing, caused a lot of discontent amongst the workforce. A fact acknowledged on both sides of the negotiations. Imagine getting a job and working alongside people doing the same job, and yet you will never receive the same pay. Many of these workers had close relationships with one another as well, which only made the disparity more difficult to bear for some.

In an excellent article for The Nation about the growing trend of tiered wages in the US, Louis Uchitelle talks about a father and son, Gary and Karl Hoeltge, who both work on a GM assembly line in St. Louis. Karl feels disillusioned with the work and has his sights set elsewhere, in part because, “I’ll never catch up to my father’s pay—not if the union allows the present setup to continue.” Uchitelle describes how father and son must refrain from discussing the issue at the dinner table so they don’t upset the rest of the family. The divisiveness of wage tiers seeping into home life is important to note, because one can imagine how those same feelings must render themselves in the workplace.

The Hoeltge’s paint just one example of the discontent that many autoworkers felt in regards to the tiered wage system. Trey Durant, a 20-year factory employee for Chrysler, has strong feelings on the issue, “Working in the same facility, side by side with someone who has a different wage than you was a bad idea, even though I know why they had to do it when times were tough,” He says. “I want my brothers and sisters to be at full wage also.” And even FCA CEO Sergio Marchionne, whose company benefited the most from this arrangement, called the system unsustainable and pushed for it to end.

The UAW worried that the increasing number of tier two employees at the factories would more firmly entrench the system. Whether they worried about younger workers making ends meet as Trey Durant says or worried about being forced out for cheaper labor themselves is anyone’s guess. What we do know is that the unions made ending the two tier system a key point in labor negotiations with the Big Three in 2015. Ultimately, they reached an agreement that instituted a new eight-year track for new hires to eventually reach the same wage rate as tier one employees. So the controversial wage tiers are no more.

Conclusion

Ford utilized the advantages of tiered wages when in-sourcing jobs back from Mexican plants, but now they have to rethink their strategies. “The business case for in-sourcing is more challenged with today’s agreement versus the prior agreement,” said Joe Hinrichs, Ford’s President of the Americas to Automotive news. “…there will be business choices over time that will have to be looked at, given the new cost structure that we have.” These wage structures made it economically beneficial for the big Three to keep jobs in the US, and now that they’re gone it will be interesting to see what actions they take next to try and keep earnings high. The bail-out and tiered wages certainly helped punch up the economic recovery, but how will these companies choose to compete with foreign competition going forward?

For the worker, the ever evolving market place, in the end, is the primary difficulty they have to face. Tiered wages may have cause unrest amongst the employees, but ultimately they allowed many people to attain jobs they otherwise would not have. Faced with the looming threats of increased automation and further outsourcing to Mexico it appears many of these workers have picked a losing fight.