The debate surrounding Catalan independence has swirled with varying degrees of fervor for hundreds of years. Back in the 1600’s Catalans fought for freedom from the Spanish crown in the Reaper’s War which they ultimately lost. Since then the region has remained in a strained relationship with the Spanish Central government. Whether that government was a monarchy, democracy or fascist dictatorship the Catalans have always felt a distinctly separate cultural and ethnic identity from the rest of Spain. Similar sentiments exist in other Spanish regions such as the Basque Country and Navarre, as well as other European regions such as Scotland, in the UK, and the Umbria region of Northern Italy.

In more recent years, the arguments from separatist groups have taken a decidedly more economic bend. They have been fueled by the European debt crisis and other major economic issues facing Spain, and signal a bit of a change from the arguments from yesteryear. Even during the Spanish Civil War, which was largely fought between German and Italy-backed Nationalists and Soviet-backed Communists, the Catalans were largely in league with the anarchists whose economic policies you can probably guess weren’t too fully formed based on the fact that, you know, they were anarchists.

So this new approach is a stark change of tact for independistas, but don’t let the new paint job fool you. Despite the difference in content the underlying message is the same. They are still leveraging the historic trend of Catalan mistrust of the Madrista government and deeply felt regional pride to push for an independent Catalonia. Only now their arguments center on unfair taxation and mounting regional debt, instead of language and literature.

But does this rhetoric hold up to objective economic scrutiny?

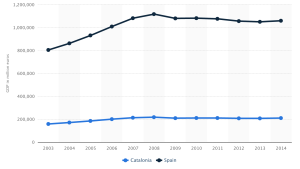

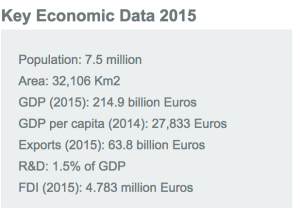

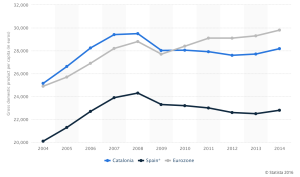

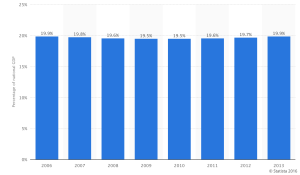

If we look at raw numbers we can see that Catalonia comprises a significant portion of the overall Spanish GDP. In 2014, Spain’s total GDP was about $1.1 Trillion, according to World Bank, with Catalonia consistently accounting for around 20% of that figure, or just over 200 Billion euros, despite only comprising 16% of the nation’s population at 7.5 million people. Catalan GDP per capita was just over 28,000 euros in 2014, just behind the Euro-zone figure of just under 30,000 euros. But it was over 20% higher than the average Spaniard, thus making it one of the wealthiest regions in the country.

Two major drivers of the region’s economy are both the export and transport of goods. Catalonia accounted for 25.5% of Spain’s total exports in 2015. Barcelona, the regional capital, is the third largest port in Spain, and Catalonia handles 70% of exports from the rest of Spain. Based on these strengths it would certainly hurt Spain to lose the one of its most economically powerful regions. It would hinder trade, and levy a sharp blow on the overall country’s overall economic output. Conversely, it could put Catalonia in danger of facing tariffs and boycotts on its goods which would harm its trade-dependent economy. Dangers loom for both sides in the event of a separation.

Catalonia Region Economic Data (Source: World Bank)

So what’s driving the Catalan’s push for economic separation? Two things: a major debt crisis and the perception of unfair taxation. But what do we find when we look at these issues more closely? Let’s look at the debt issue first.

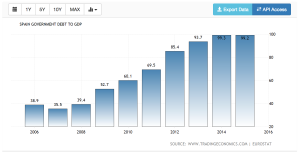

Despite the region’s economic strength it is still the holder of the largest regional debt in Spain. The meteoric rise of Spanish debt as a result of the European debt crisis was felt by the entire country, but it’s an issue that has become a particular flash point for Catalans.

Catalonian GDP per capita compared to Spain and the Eurozone (Source: Statista)

After a brutal recession in 2008, and a second recession hit in 2012 and debt in greater Spain soared from 65.9% of GDP in 2011 to 85.4% in 2012. This reality led the Spanish central government to levy harsh austerity measures in an attempt to get the debt situation under control. They froze public sector wages and cut government spending by 12%. Combined with a regional unemployment rate of 22% in 2012, Catalans came face to face with a daunting combination of economic issues.

In attempting to service the debt the Spanish government made it more difficult for regions, like Catalonia, to jump start their economy through classic Keynesian stimulus plans. This is also a consequence of the Euro currency system which does not allow individual country to create their own monetary policy in order to ease the blow of recessions. Perhaps that fact forces Madrid’s hand to austerity measures, but not many Catalans want to hear excuses for the Madridistas. The economic results, or lack thereof, of these actions certainly does not help matters. Despite severe austerity measures Spanish national debt debt rose to 99.3% of its total GDP in 2014, and then shrunk slightly to 1.1 trillion euros, in 2015.

Source: Trading Economics

The question of how the two sides will allocate this debt is essential to understanding the possible economic consequences of Catalonian Secession. If the two nations agree that the Catalans should take 19% of the debt with them, or the same amount of money they contribute to Spanish GDP, then the effects on Spanish national debt after losing the region would be marginal, because they would lose the same share of debt, as they lose in total GDP.

However, if the central government allows the Catalans to leave with 16% of the debt, which matches their population size, or even 11% which would equate to government expenditures in the region then, according to economist Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Spain’s national debt could rapidly approach unsustainable levels. Even worse, If the Spanish central government comes to no debt transfer agreement with the Catalans it could mean that they leave without taking on their share of the Spanish national debt. This would be legally dubious, but possible, and it would cause Spanish debt to explode. It’s estimated that debt levels would rise to nearly 125% of total Spanish GDP due the multiplying effect of losing the Catalan contribution to the national GDP while also taking on more debt. This eventuality could lead to a Spanish default. However, if the Catalans attempt to leave with no economic agreement they could surely expect to face harsh economic sanctions from Spain. Possibly even Spain blocking Catalonia’s entry into the EU because countries need unanimous approval for entry.

With both sides facing dangerous outcomes from secession, it can be difficult to understand why this independence movement has gained so much traction. But by investigating Spanish taxation practices we can see why so many Catalans, who are already predisposed to mistrust the central government, feel independence is their only option to receive fair treatment.

In response to central government austerity and rising debts, the Catalan regional government requested a payment of around 5.57 billion euros from Madrid, and not in the form of a loan. They wanted this as repayment for what they see as unfair taxation policies by the Central government.

According to a survey taken by the Catalan regional government in 2014, 80% of the Catalan population felt the central government taxed them at an unfairly high rate. In the populace’s view, too much money was taken without reinvesting enough of it back into Catalan infrastructure and social programs. These concerns led to the slogan, “España nos roba,” (Spain is robbing us), and fueled the pro-independence parties that were elected throughout the region in September 2015.

The question of whether Spain is truly “robbing” the Catalan people quickly becomes more complicated than it initially appears, and certainly more complex than the independentistas of Catalonia want their supporters to believe.

If we use the figures given by the Catalan government, they lose 8.5% of its GDP to the central government every year. Independentistas argue that if they left Spain then this money would simply stay in the region for the people to use at their own discretion and help curtail their rising debt. Those on the remain side respond that if you take into account the amount of public spending on services and infrastructure paid for by the national government then this number of “saved” GDP would shrink to around 4-5%.

Source: Statista

Around the world, it is not uncommon for a wealthy region, such as Catalonia, to pay a higher share of taxes that are then redistributed to less wealthy regions. A 2014 study by Wallet Hub illustrates how this very principle exists here in the US. For example, a state like New Jersey received only $0.88 for every dollar they put into federal income tax. Meanwhile Mississippi, a relatively poor state, gets $3.07 back for every dollar they put into the system.

So if this happens regularly elsewhere are the Catalans just being unreasonably greedy? Maybe, but maybe not.

In a 2012 study published by Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra University, researchers found that Catalonia accounted for 118.6%, of national taxes per capita which placed it third out of the 15 regions in Spain. After the redistribution of taxes its per capita distribution of tax money fell to 99.5% of the national average, placing it 11th. Conversely, Extremadura, a remote, mountainous region along the Spanish border with Portugal, which ranked 14th in national taxes per capita at 76.6%, rose to third place in per capita tax revenues after redistribution by receiving 111.8% of average government resources per capita.

Taking a step back, it’s clear that a combination of austerity tactics to cut down debt and improper tax redistribution created an environment ripe for separatism, though some analysts hold out hope that the situation can be rectified. “We continue to believe that the secessionist fervor is a response to fiscal austerity,” analysts at Credit Suisse say. “Much of it would calm down if the Madrid government re-negotiates intra-regional transfers with Catalonia and the region is allowed to have more tax autonomy.”

Catalans can point to the Basque Country and Navarre regions of Spain, as examples of fiscal policy that, if granted to Catalonia, may help settle talks of secession. Both of those regions have agreements with the central government allowing them to keep most of their tax revenues without sending them to the Spanish government. Perhaps if the central government institutes smart changes, or merely weathers the storm, then the winds of secession will die down.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.