In October of 2016, telecommunications giant AT&T agreed to buy Time Warner for $85.4 billion. This merger would bring together a content distributor with a juggernaut of content production.

The deal was set to close by the end of 2017 until the Department of Justice stepped in. On November 20th, the Justice Department sued to block AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner.

This case has the potential to be a landmark case and a sign of changing antitrust tides in the Justice Department. This result of this case could have implications beyond this one deal.

The Great Content Desire

AT&T is a multifaceted telecommunications company and Time Warner owns channels and produces originals TV shows and movies. Their businesses intersect but do not compete. AT&T wants to acquire Time Warner so it can pair its existing content distribution streams with Time Warner’s content production.

AT&T divides up its company into four operating segments: business solutions, entertainment group, consumer mobility and international. Consumer mobility is the segment traditionally associated with AT&T and provides wireless service in the United States. The entertainment group, which includes recently acquired DirecTV, some content production, advertising and broadband internet, is at the heart of the conflict around the merger.

AT&T wants to acquire Time Warner so it can own its premium content produced by HBO and Warner Brothers and the content produced by the channels of Turner Broadcasting, which includes: CNN, TBS, TNT, TruTV, among others. The merger would also give AT&T the sport broadcasting licenses Turner Sports including the rights to NCAA march madness. It is this mass of content production that AT&T is craving.

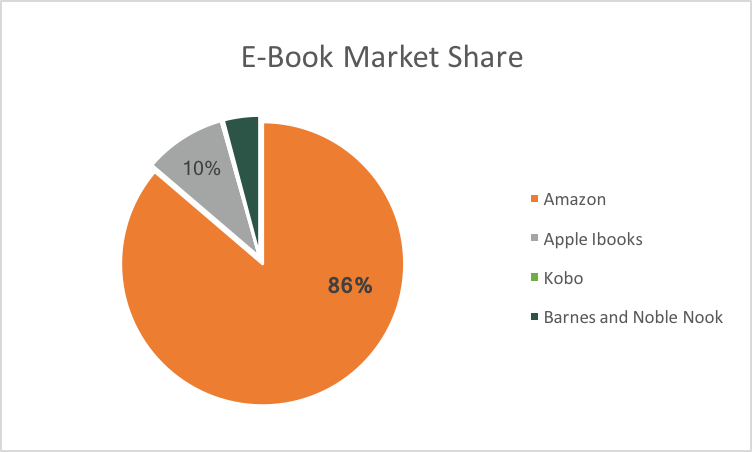

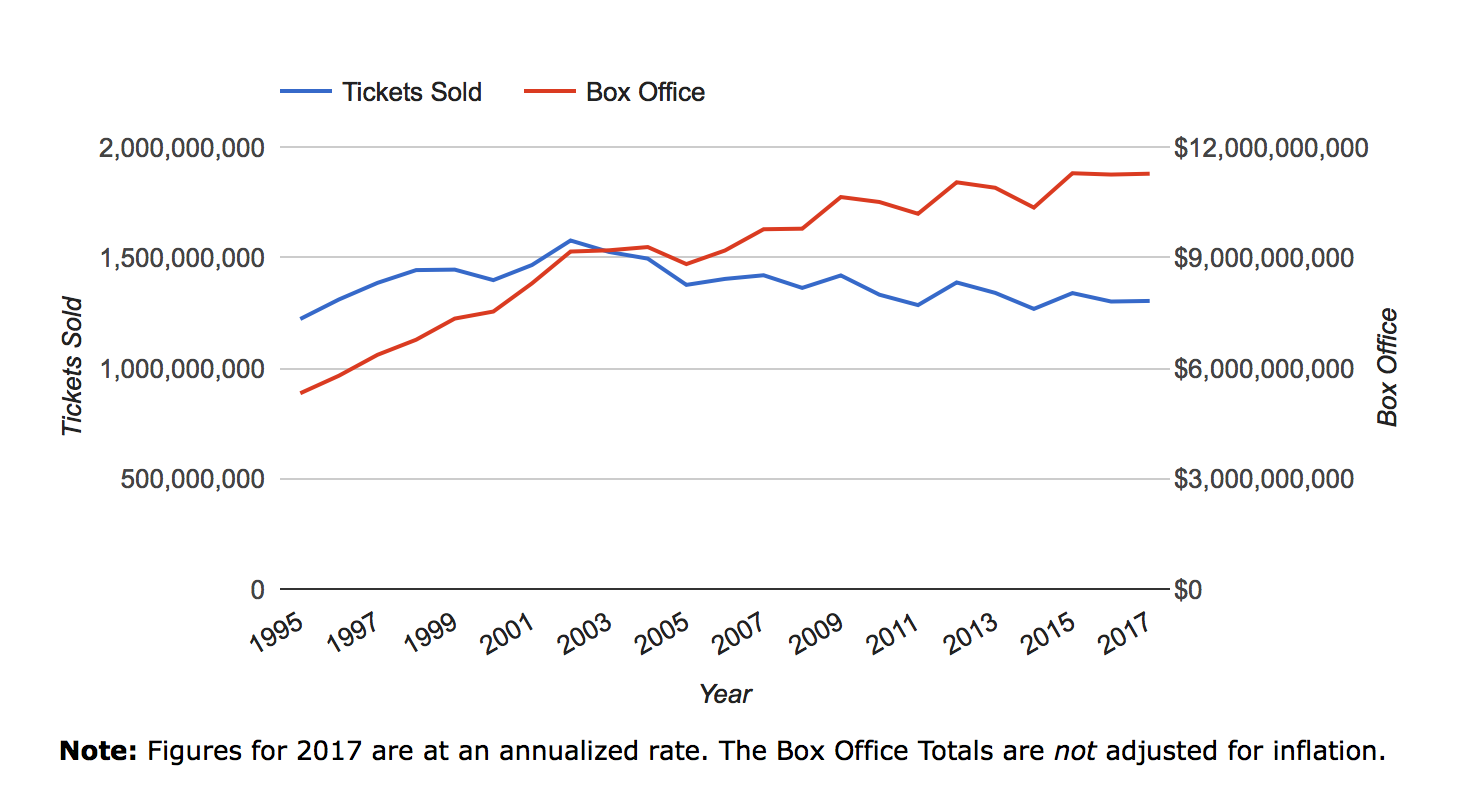

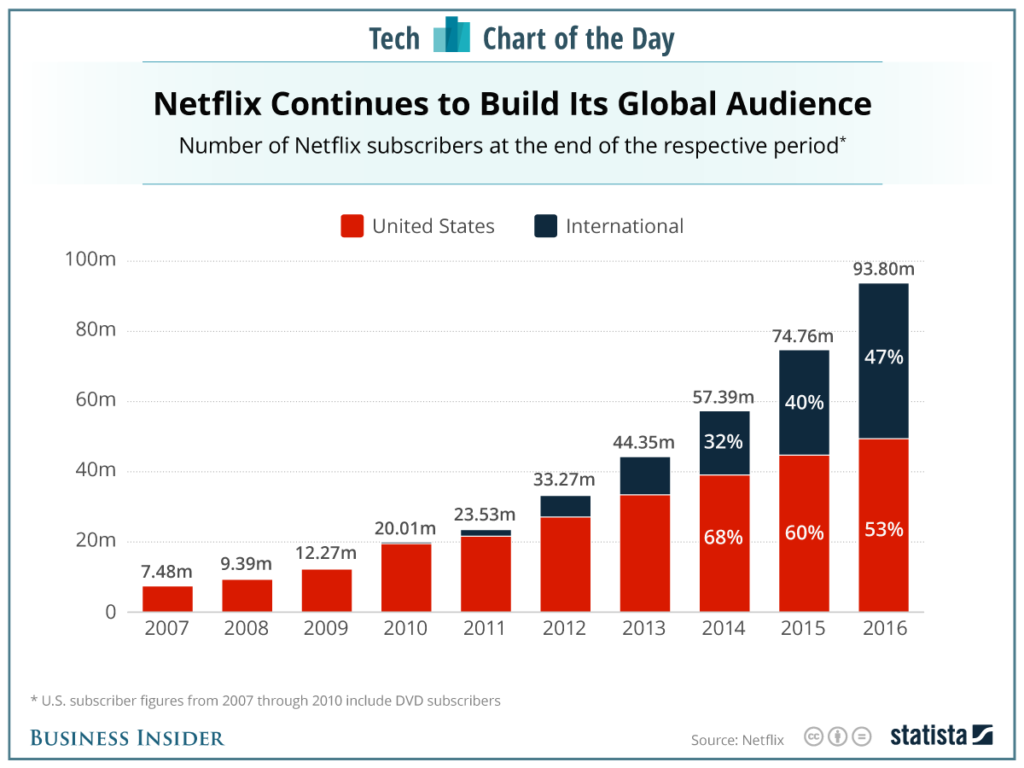

Across the tech and telecommunications industries, there is a general hunger for content and content production, especially as there seems to be no slowing down of online streaming content. Everyone is trying to keep up with and compete with Netflix. For example, Apple recently invested $1 billion to produce original TV shows and movies. AT&T’s motivation behind the merger is its hunger for content.

Merging with Timer Warner would diversify AT&T’s entertainment portfolio and allow them to become a competitor of streaming giant Netflix. If the deal goes through AT&T would have a control over both premium content production and content distribution channels, like DirecTV and their wireless cell phone service.

Vertical Merger

There two main types of mergers: vertical and horizontal. Horizontal mergers, when direct competitors merge, raise more concerns of a reduction in competition. When two competitors merge they are directly reducing competition in a field.

The AT&T and Time Warner are not direct competitors; therefore, their merger is a vertical merger. In this vertical merger, it would be a unification of a distributor, content distribution platforms of AT&T, with a supplier of a product, the content produced by Time Warner. Technically, by merging there is not a removal of competition in the market. Before and after the merger there will be the same number of wireless service companies and TV cable and satellite companies.

While this merger is vertical, AT&T has also pursued horizontal mergers in the past. In 2011, they ended an effort to acquire T-Mobile. That merger would have directly decreased, already limited, competition in the wireless service market.

On a conference call with reporters in 2016, AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson reportedly said “This is not the T-Mobile deal; there is no competitor being removed from the marketplace…Time Warner is a supplier to AT&T. It’s a classic vertical merger.”

The goal of United States anti-trust law is to ensure competition and prevent the creation of monopolies. Since horizontal mergers directly reduce completion and could lead to monopolies the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have historically been more vigilant in blocking and preventing horizontal mergers.

The government has only challenged 23 vertical mergers since 1979. Of those 23, three were abandoned by the companies and the other 20 were approved. The government has never won a vertical merger court case.

Effects of the Merger

AT&T’s argues that the goal of acquiring Time Warner is to “give customers unmatched choice, quality, value and experiences that will define the future of media and communications.” They say that the deal will lead to benefits for both investors and consumers.

Some of the possible consumer benefits that AT&T is promoting includes new video innovation and the potential alternative to cable. AT&T in a press release said that “the combined company will strive to become the first U.S. mobile provider to compete nationwide with cable companies… It will disrupt the traditional entertainment model and push the boundaries on mobile content availability for the benefit of customers.”

There is the rationale laid out by AT&T for why this deal should proceed, but there are also legal scholars who believe this deal should go through because if it is successfully blocked by the government there would further reaching consequences.

In the Harvard Business Review, Larry Downes argues that if this deal is challenged then “other pending or likely mergers,” like Disney and 21st Century Fox, “will be thrown into chaos—and the stock markets along with them.”

In addition to the possible positive effects of the merger that are possible negative consequences. Just because the merger technically would not directly reduce completion, it doesn’t mean there isn’t any risk of this merger resulting in anti-competitive practices.

Time Warner owns three of the top basic cable channels, the top cable news network, and the top premium cable channel. AT&T, thanks to its acquisition of DirecTV, is one of the largest distributors of those channels and their content. When AT&T owns both the distribution network and the content, they have the ability to withhold or increase the price of the content from Time Warner.

For example, they can raise the price of HBO and CNN. This could, in turn, drive customers away from other cable companies and to AT&T owned distribution networks or just lead to a customer having to pay more for AT&T owned content. They would be able to use the leverage of Time Warner’s “must have programming” to restrict competition and give their platforms an advantage. The acquisition of Time Warner would give AT&T the opportunity to stifle its competition through its ownership of highly desired content.

However, Harvard Law School Professor Susan Crawford points out in a Wired article that AT&T’s response to this claim would be that they have “every reason to ensure that Turner content is seen as many places as possible.” She also notes that this argument is flawed as “the revenue AT&T loses by effectively locking competing providers out of its must-have content will be more than made up for by those new subscriptions—available nationwide through DirecTV.”

Possible Solutions

The case most similar to the AT&T Time Warner deal is Comcast’s acquisition of NBC Universal, but the Comcast merger never went as far as with DOJ as the AT&T case has. The Justice Department did not sue Comcast to stop the merger. The DOJ allowed Comcast to buy NBC Universal as long as they agreed to over 150 conditions meant to prevent Comcast from favoring NBC content.

Behavioral conditions, like the ones in the Comcast case, have been a common way the government has dealt with vertical mergers. These measures are harder to ensure are followed and not a foolproof way of preventing anti-competitive practices.

The current head of the antitrust division at the department of justice, Makan Delrahim, has spoken about his dislike of the behavioral remedies in merger cases. In a recent speech, he said that “our goal in remedying unlawful transactions should be to let the competitive process play out. Unfortunately, behavioral remedies often fail to do that. Instead of protecting the competition that might be lost in an unlawful merger, a behavioral remedy supplants competition with regulation.”

Delrahim’s aversion to behavioral conditions hints to an avoidance of this as the solution to the AT&T case.

The alternative to behavioral conditions is structural remedies. These structural solutions, also known as divestitures, force a company to sell off a part of their business. Maurice Sucke, a professor of antitrust at the University of Tennessee College of Law said that structural remedies “are much easier than behavioral remedies to craft and enforce.”

Prior to the department of justice suing AT&T over the merger, it was reported that A

T&T met with lawyers from the DOJ to discuss possible divestitures. It has been reported that AT&T was urged to sell off either Turner Broadcasting, which includes CNN, or DirecTV for the deal to go through. AT&T showed no interest in these divestments. In a news conference after the DOJ decision to sue, AT&T, Stephenson said that his company was not willing to give up any assets to get the deal approved.

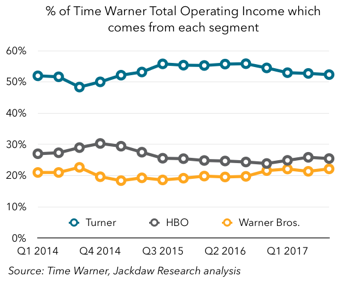

In Variety, Jan Dawson argues at AT&T needs all parts of Time Warner in order to justify the merger. Turner, which CNN is under, is the most financially profitable segment of the Time Warner business. It has contributed half of its operating income in most recent years. So while, Turner is not the premium content contributor, like HBO or Warner Brothers, that AT&T was originally seeking it does provide its income is important. Dawson’s analysis helps to explain the rationale behind AT&T’s lack of interest in selling off any part of its existing company or Time Warner.

The Political Question

This proposed selling off of CNN has raised some political questions due to the President’s feud with the news network. It is not known if the President had any influence over the DOJ’s decisions in this case.

However, if he did exert influence on the DOJ, “Mr. Trump will become the first president since Richard Nixon to use the levers of executive power to threaten the economic interests of a news organization whose coverage he does not like,” wrote Jim Rutenberg in the New York Times.

Even if there was no specific intervention by the President, Daniel Lyons, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said that AT&T counsel could argue that “these divestiture requirements are not motivated by the fact that the Justice Department thinks that divestiture is necessary to prevent consumer harm but instead that this is motivated by a more political purpose”

What’s Next

Following the lack of agreement over divestments, the DOJ proceeded to file a case against AT&T. Cecilia Kanf and Micahel J. de la Merced wrote in the New York Times that the DOJ suing AT&T is “setting up a showdown over the first blockbuster acquisition to be considered by the Trump administration and drawing limits on corporate power in the fast-evolving media landscape.

In a statement on the decision to sue, Delrahim said that “this merger would greatly harm American consume it would mean higher monthly television bills and fewer of the new, emerging innovative options that consumers are beginning to enjoy.”

Moving forward the DOJ has indicated they would still be willing to negotiate a settlement with AT&T, however, if they cannot reach an agreement the case will go to court. There is very little precedent for a vertical merger antitrust case going all the way to court.

The result of this case could also signal a change in antitrust regulation enforcement in the United States. It could affect the result of other pending or proposed mergers. For example, it could have implications for Disney’s exploration of acquiring 21st Century Fox.

It could even have ramifications on verticals mergers in entirely different sectors. CVS recently announced its acquisition of insurance company Aetna, a healthcare vertical merger. The result of the AT&T Time Warner case could set precedent for the DOJ or FTC’s actions regarding the CVS merger.

In the end, the lack of precedent in cases like this leaves a lot of uncertainty of what happens next. The justice department could continue to be lenient on vertical mergers or change course entirely and affect all vertical mergers to come.

Sources

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-20/at-t-is-said-to-face-u-s-antitrust-lawsuit-over-time-warner

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/21/dojs-lawsuit-to-sink-att-time-warner-deal-is-short-sighted.html

https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2016/10/att-time-warner-merger-paper-000224

https://www.wired.com/2016/11/the-att-time-warner-merger-must-be-stopped/

https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/10/25/499185907/the-at-t-time-warner-merger-what-are-the-pros-and-cons-for-consumers

https://nypost.com/2017/11/30/why-consumers-should-fear-the-att-time-warner-merger/