A healthcare provider, an insurance payer, and a patient all walk into a bar. You already know how well this is going to go.

National Health Expenditure; that is, the amount the United States spends on healthcare each year, was $3.3 trillion dollars in 2016. That’s $10,348 per capita or 17.9% of GDP. The OECD average in the same year was $4,003 per capita or 9% of GDP.

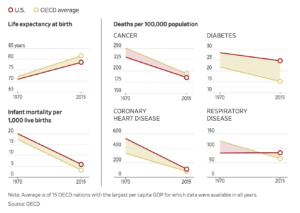

We have a dataset showing that we spend more, disproportionately more, on healthcare services than our fellow OECD members; that’s clear. But spending money is not inherently bad. But in exchange for these expenditures, nearly $6,000 more per capita, we must expect superior results. We must expect our citizens to have less chronic disease, higher life expectancy, and lower infant mortality rates, but we do not see that realized. The Wall Street Journal published the following infographic in July, illustrating the failure of the American healthcare system in comparison to our fellow economically-developed nations.

This story, the story of why it is happening and how it can change is excessively complex, and conversations on all chapters of this story deserve to be had and heard. I’m going to discuss one element of this story, one that I believe sheds the most light on what is actually going on in our system—the payer-provider relationship that makes the patient, the payer, and the provider all worse off.

There are three main players in this game, the three walking into a bar—provider, payer, patient. What does each player want?

The patient wants to get treated, treated well, and treated well at a good price.

The payer (also known as the insurance company) wants to provide care at the cheapest level of care possible that will meet the patient’s minimum requirements.

The provider wants to treat the patient at the highest cost while maintaining exclusive relationships with the payers. The insurance companies are ultimately the ones to pay the bills.

The payer-provide relationship is a complex one to say the least. Let’s look at it through the lens of Mr. Edward Winchell. Mr. Winchell is a 65-year-old, California resident who was admitted to Mercy San Juan’s hospital facility for a right hip fracture in 2014—he had fallen down. Throughout his time at the hospital, Mr. Winchell began suffering from symptoms of C. difficile, or inflammation of the colon that can cause severe colon damage or even death. According to the public record complaint filed on Mr. Winchell’s behalf, Mercy San Juan attempted to discharge and relocate him to a skilled nursing facility once his Medicare coverage was due to expire; however, the hospital “consciously or reckless[ly] chose to omit the fact that Mr. Winchell had C. difficile from his records,” knowing that such a condition would make him an undesirable candidate for another facility—he was deemed too expensive to care for. “Mr. Winchell was unsafely discharged” to a skilled nursing facility with no knowledge of his presenting symptoms. This is a phenomenon called “patient dumping” where providers will essentially pawn off patients that are too expensive, or for whom their insurers won’t pay, to lower, cheaper care facilities. The end of the story? Mr. Winchell’s colon was removed and will be forced to use a colostomy bag for the remainder of his life.

This story is both devastating and disheartening, but let’s look at it from a business perspective. The hospital, Mercy San Juan, had an expensive patient. The insurance provider was nearing the end of its contractual agreement to pay and was refusing to pay any more. The hospital could not deliver care at a cheaper rate, but a skilled nursing facility could. Therefore, the logical option for the hospital is to transfer the patient to that cheaper facility. This cheaper facility also ends up delivering a lower level of care, precisely the opposite of what Mr. Winchell actually needed to be discharged more quickly and more safely.

Health care is an industry, though often forgotten, an industry with a vibrant economy. Each firm is competing against the other in an attempt to claim profits, just as firms in the automobile or CPG industry do. The only difference is the extreme amount of influence that the suppliers—in this case, insurance companies—command over the firms.

So what are the consequence of this payer-provider relationship, of this patient dumping, of this subprime care?

To examine these consequences, hospital readmission rates become a useful tool. Theoretically, if a patient is treated with poor levels of care before being discharged, they will have to return to the hospital again in order to receive the care they originally needed. This scenario is illustrated by hospital readmission rates. Though data are severely disjointed, one study published in the AAP Journal examining this rate among children with chronic complex conditions (CCCs) reveals that, among children with 1 or more CCC, 19% had at least 1 readmission within 30 days of discharge. In patients taking 8 or more medications, that number was 29%.

In 2011, The New Yorker ran a story following doctor Jeremy Brenner playing around with data in a New Jersey town. Brenner “found that between January of 2002 and June of 2008 some nine hundred people in […] two buildings accounted for more than four thousand hospital visits and about two hundred million dollars in health-care bills. One patient had three hundred and twenty-four admissions in five years. The most expensive patient cost insurers $3.5 million.”

Another wide-spread analysis found that 14.4% of 12.5 million discharged patients were readmitted. These readmissions resulted in annual costs of $50.7 billion.

Of these hospital readmissions, 26.9% are considered potentially preventable.

These hospital readmissions are discouraging and costly, but they also represent an impossible relationship between provider and payer. Due to pressures from insurance companies, hospitals are financially pressured into discharging, often prematurely, patients such as Mr. Winchell in order to cut costs down for the payer. Insurance companies, you recall, want the patient discharged as quickly as possible in order to cut down costs. However, when these patients are forced to return to the hospital to receive adequate levels of care, like those 26.9% are, these hospitals are hit with large fines (3% of total Medicare payments in 2015). This puts the providers in the ultimate Catch-22. Do they discharge the patients and risk readmission penalties or keep the patient longer despite the provider’s refusal to pay, which will naturally eat into the hospital’s bottom line and destroy relationships with insurance companies?

Herein lies the prisoner’s dilemma: with incomplete information, neither payer nor provider knows how to best treat a patient at the lowest cost. As a result, the dominant strategy for the payer will always be the lowest cost option that produces the lowest level of care, an option that will indeed result in increased costs for the provider as the patient is readmitted yet again.

Both readmission rates and the penalties slapped on these readmissions argue that poor care inevitably ends up costing everyone more in the long-run—more pressure and time for the provider, more money for the payer, more grief for the patient. Even more, these numbers tell a story, a powerful story that shows the careless costs within the American healthcare system that make the payer, the provider, and the patient all worse off. Can we shave $50.7 billion off the total National Health Expenditure by simply improving this relationship?

This is not even to speak of the effects that incentivizing proper nutrition and exercise, addressing the pharmaceutical market, and reforming regulations on price of care could have on this cost. If we analyze this situation from purely a financial standpoint, completely ignoring every humanitarian, moral, and ethical argument, our healthcare system is inefficient at best and damning at worst.

Healthcare spending affects more than just the chronically sick; it affects you, the taxpayer, whose dollars directly fund our national budget.

As data from CBPR shows, Medicare and Medicaid represent roughly 26% of our national budget—that 26% is part of our “mandatory” spending, the part of our budget that politicians claim we can’t touch.

I would argue that we can touch mandatory spending. We can shrink it through lowering hospital readmission rates, through raising the level of care, through changing policy to encourage collaborative behavior between provider and payer, not pitting them against one another.

A healthcare provider, an insurance payer, and a patient all walk into a bar. Let’s not let them get into a bar fight.