It has been exactly a decade since the financial crisis swept all across the globe in the fall of 2008, but for many countries and economies, the issues brought upon remain very much alive, and the aftershocks can still be felt today. As countries and economies already were functioning in each of their own unique ways, they had put forward different monetary and fiscal policies in response to the financial crisis, and were met with varying results. Among the many distinct measures taken was Britain’s highly controversial Austerity Programme. First officially proposed by both Labour and Conservative Party during the 2010 General Election, and subsequently implemented by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, its impacts have persevered over the past decade, and are as relevant now as ever. Though the process of leaving the European Union (Brexit) has since replaced it as the top national issue in Britain, Prime Minister Theresa May recently brought the attention back to the Austerity Programme with her central message at the 2018 Conservative Party Conference “The end of it is in sight.” It remains to be seen whether the claim turns out to be valid, but there should be little doubt the Austerity Programme has reshaped the British economy as well as millions of people’s lives, for better, and, yet, for worse.

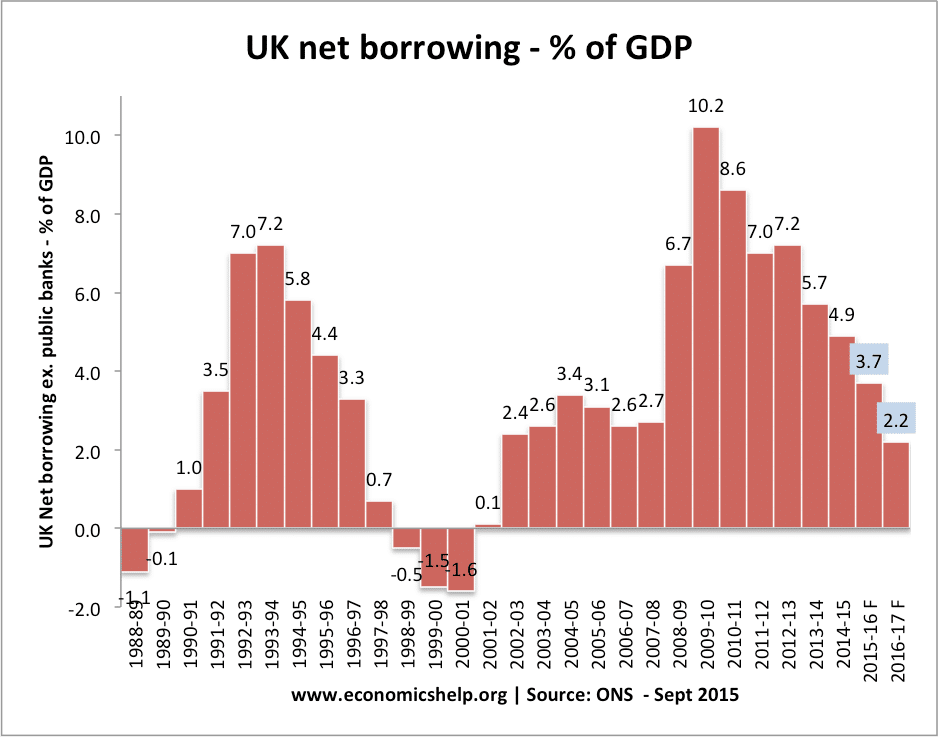

To determine how effective the Austerity Programme has been, one has to first fully understand the context it was conceived in. When the United Kingdom was due to go into election season in April 2010, the financial crisis had been in full effect for over 18 months already, and the damage it had dealt the UK was painfully obvious. Having previously produced a strong and stable economic growth for three terms of parliament spanning a decade as the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown had to go through his own election campaign as the Prime Minister who was in the middle of it all when the financial crisis hit. A mere 5 years prior, he, along with the economy he produced, was widely credited as the real reason why Labour was able to win the election, in spite of Prime Minister Tony Blair’s unpopular decision to invade Iraq in 2003. Now, in 2010, the most notable thing associated with his name was a peacetime record high deficit £157 billion, highest figure in Europe second only to Ireland, as well as a 300% increase in net borrowing in proportion to GDP between 2008 and 2010. Admittedly, there was no guarantee that, had the financial crisis not happen, Gordon Brown would have won the 2010 General Election fair and square. Nevertheless, it had indubitably dealt quite a heavy blow on his premiership in its infancy. The seemingly ridiculously high borrowing numbers became an opportunity for political attack, something a strategist and tactician such as the then Leader of Opposition, David Cameron, would not, for a second, hesitate to seize. During Prime Minister’s Questions on October 29, 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, accused Brown and Alistair Darling, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, of breaking the fiscal rules that they had set up. “Rule 1 was, ‘Only borrow to invest’; now he is having to borrow to pay for unemployment benefit. That rule is dead. Rule 2 was, ‘Don’t have debt over 40 per cent of national income.’ Even on his own fiddled figures, that rule is now dead.” (Hansard) Not complacent with simply dishing out criticism, he followed it up six months later in April 2009, proposing an “age of austerity” as the potential Prime Minister.

He did not have to wait long before he got the chance to turn the potential into reality. The largest party coming out of the 2010 General Election but without a majority in the parliament, the Conservative Party formed a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats in May 2010. A month into the new government, Chancellor George Osborne announced in the emergency budget dramatic government spending cuts, a Value-Added Tax increase from 17.5% to 20%, welfare cuts, in addition to a personal allowances increase of £1,000. Osborne claimed such measures would be “tough, but fair”, and “unavoidable”, while calling the previous government’s massive spending in response to the financial crisis “irresponsible”. With the new budget, the coalition government had cutting the aforementioned deficit and lowering debt to GDP ratio as its top priorities. With new policies going in the opposite direction of the previous Labour government, the coalition set out to fix the financial problems as much as they could, if not at the cost of people’s living standards. Increased Value-Added Tax without increased wages meant goods were less affordable than before, and welfare cuts, most notably child benefits and pregnancy grant, meant another hit on people who needed them. The downsizing on public sectors unsurprisingly led to an increased unemployment rate during a period in the following year. Granted, while it was true that the post held tremendous power over monetary and fiscal policies, the Chancellor or the Exchequer had always been a far cry from an easy and popular job. Former Chancellor Norman Lamont, infamously known as the man responsible for Black Wednesday, called himself “the most hated man in England” after being appointed. Osborne’s public image, likewise, was practically destroyed by his direct link to the Austerity Programme, as he was perceived as the guy who simply and solely took goods and services from the British people for his own personal good. As the years went on, the coalition government did nothing to shy away from the austerity route, even adding privatizing public assets into their arsenal, with the privatization of Royal Mail causing most controversy. Despite the fact the United Kingdom’s net borrowing in proportion to GDP had been effectively cut down at the end of the parliament to half of the 2010 figures, one cannot help but wonder if it was worth the sacrifices made elsewhere in people’s welfare, purchase power, and since this was a British topic, the traditions.

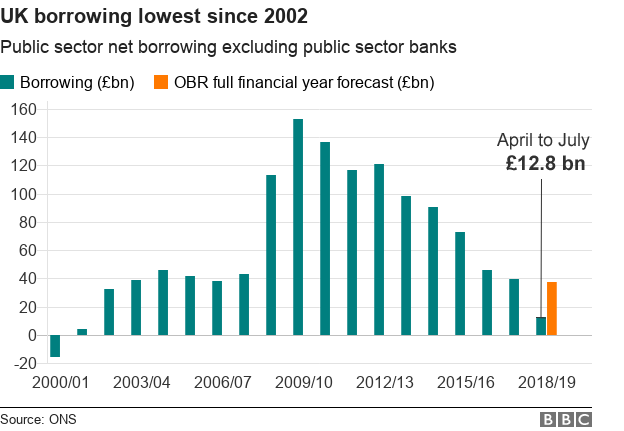

Fast forward to today, over two years after the man behind the Austerity Programme had been removed from power, the effects of the programme are still pervasive and prevalent. Whilst the former Prime Minister-in-waiting has been doing his best Niccolò Machiavelli impression as editor of the Evening Standard, his predecessor has generally followed his footsteps, and steadily furthered the progress of the Austerity Programme. In his spring 2017 budget, current Chancellor Philip Hammond cut down on more benefits for working age people, and confirmed that he intended continue with the Austerity Programme during the 2017 General Election campaign. With a business background before entering parliament and “Spreadsheet Phil” for a nickname, Hammond is much less of a politician than Osborne ever was, but it was evident that his main goal was still to tackle the deficit. A year later, in August 2018, it was announced the government had turned in a surplus of £2 billion with a net borrowing of £12.8 billion, both new records since when Gordon Brown was steering the ship as Chancellor. However, it is important to look at both numbers in context. The United Kingdom GDP growth has fallen from a steady 1.7% to 1.1% at the beginning of the year, so the record numbers might not necessarily mean everything is fine and dandy. An extended period of decrease in GDP growth means the UK is at rick of bottlenecking the economy, which would defeat the very purpose of the Austerity Programme.

Just a few weeks after Prime Minister Theresa May had vowed the austerity was in its last leg in the 2018 Conservative Party Conference, and less than two weeks until Philip Hammond is due to reveal a new budget, it is quite the tricky time to comment on the future of the Austerity Programme. The United Kingdom has indeed made strides in fighting back the financial crisis with a distinct and decisive strategy, but it also introduced problems that were not present before the programme took effect. If the claim had not been purely a decoy to distract people from the mess that is the Brexit fiasco, the British people can expect real changes in the upcoming budget, given the Prime Minister’s bold claim and the most updated figures. The budget may include increased public spending, considering the newly-found liquidity in the government budget, but it would not necessarily mean a complete derail from the Austerity Programme. After all, Hammond has been merely functioning in the George Osborne-shaped mold so far. The Austerity Programme has been the dominating driving force in the British society for the better part of the past decade, and even if it were to go away in the foreseeable future, it would not do so quickly, and it is entirely likely the country would still be haunted by certain policies left over, or simply the everlasting memories of it. Moreover, mind you, the “Austerity Chancellor” himself is still young enough, relevant enough, and dare I say it, more politically charged than ever. Now that he has recovered his public image as time passed, who is to say that he is not lurking for a better time to mount a comeback for the top job?

Sources:

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2009/apr/26/david-cameron-conservative-economic-policy1