Education: A Catalyst in Gender Pay Gap

In President Barack Obama’s 2015 State of the Union Address, he stated that women “make 77 cents for every dollar a man earns.” If a woman had a dollar, or even 77 cents, for every time she heard that statistic, it would cover lunch for a week. While this statistic, a ratio of two medians for full-time, full-year workers, can be problematic in that it doesn’t account for pay for the same work, it is true that a gender pay gap still exists in the United States; the female-to-male earnings ratio in 2016 was only 80.5%, although up from 70% in 1990 (U.S. Census Bureau).

Determining the causes of the gender pay gap is not a simple task. Communication surrounding the disparity is plagued by inaccuracies, as evident in Obama’s SOTU. Media coverage tends to say that the gap is caused by discrimination. Claudia Goldin, professor of economics at Harvard University, explains that while this was once the case, it is no longer a significant cause. She also reasons that another popular argument, categorical differences such as competitiveness and negotiation skills, doesn’t go the full degree in explaining the pay gap either. When featured on the Freakonomics podcast “The True Story of the Gender Pay Gap,” she deemed that the main reason for disparity is the high cost of temporal flexibility, valued more by women than men.

Temporal flexibility is “the variation in the number of hours worked and the timing of the work” (Oxford Reference). Women value this flexibility so highly because they disproportionately have caregiving obligations—watching the kids, looking after their parents, assisting sick family members, etc.—which require them to work differently. It is important to note that not all women desire this temporal flexibility. In fact, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth found that in 2006, women without children or spouses earned 96 cents for every dollar a man earned. The gap between men and women who place similar amounts of importance on temporal flexibility is somewhere in the 95% range, according to Princeton Professor Anne-Marie slaughter, who was also interviewed on Freakonomics. But since many other women disproportionately dedicate time to caregiving without compensation, they are willing to pay the high costs for flexibility of hours scheduled and worked.

This high price that women pay is reflected in their salaries. Glassdoor reports that the top five jobs in which women earn less than men, four of which are the following: chef, dentist, c-suite, and psychologist, all of which have at least a 27.2% base pay difference. The costs of temporal flexibility in these types of jobs are the highest because they are so specialized. A chef’s signature dish cannot be made by a different chef, and a patient’s wellness is dependent on his intimate relationship with his specific psychologist. These workers aren’t substitutable, so the handoffs are more costly. These handoff costs are reciprocated to costly workers, who work fewer or their own hours and thus cause more handoffs.

When women enter these types of careers, they are initially paid similar wages to their male counterparts. However, when they begin to have children, or start caring for someone else, they can no longer adhere to the requested hours set by their employers. Since they cannot devote all of the hours needed by their clients to them, they don’t receive raises, aren’t made partners, and can’t grow their careers. Women work fewer employer-requested hours and consequently notice negative effects on their salaries. The high cost of temporal flexibility is a partial cause of vertical segregation, defined by Stanford University’s Topic Report as “the overrepresentation of a clearly identifiable group of workers in occupations or sectors at the top of an ordering based on desirable attributes.” In this case, men are overrepresented as c-suite workers, dentists, etc. because they possess a desirable trait—a low value on temporal flexibility.

The difference in the value of temporal flexibility by gender also influences horizontal segregation, “the concentration of men and women in professions or sectors of economic activity” (Stanford). In choosing occupations, men tend to choose sectors where levels of responsibility are high. The UNC Population Center published North Carolina’s largest jobs by sex, and men’s were drivers, managers, supervisors, laborers, and salespersons. The majority of these do not allow for flexibility in work hours, an adverse effect of requiring lots of responsibility. Inversely, many women go into careers that are compatible with their family lives. In North Carolina these were elementary school teachers, nurses, secretaries, and health aides. The flexibility for teachers and nurses stems from their abnormal work schedules. Teachers work shifted hours, which align with children’s school schedules. They additionally have summers off and longer holiday breaks. Nurses do not have typical 9-5 hours either. They have options to work night shifts, allowing them to be home during the day. These types of occupations offer more part time employment opportunities and have smaller penalties for career pauses, so women gravitate toward them.

There is a bright side, though. In 2012, Pew found in its analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau data that the number of women enrolled in college outnumbered men by 11%, (See Appendix A). And female earnings increased 2.7% from 2014-2015, while men’s only increased 1.5%. Hence, the gender pay gap is shrinking. Hannah Rosin, in her Atlantic feature, “The End of Men,” argues that economic success is shifting away from being determined by attributes typical of men, e.g. physical strength and stamina. More women are entering the work force. Women entering new fields are dedicating less time to unpaid domestic work, making them more valuable workers who are paid more. This also creates a new need in the labor force for domestic workers. These jobs are being filled by women. The typical working wife earns on average 42.2% of the household annual income, which was 2-6% in 1970. Four out of ten mothers are now the primary moneymakers in their families. Wage gaps are shrinking for these ideologically normal women who have traditional families and are of high socio-economic statuses. But how can the United States shrink the gender pay gap for all of its women?

The countries with the smallest gender pay gaps are Iceland, Finland, Norway, and Sweden–all Nordic countries, whose populations combined roughly equal that of Texas. They’re all also welfare states with little population diversity. The differences between the United States and the Nordic countries are significant in explaining their differences in gender pay and illustrative of why they will continuously rank highly while the U.S. will not.

Over time, traditionally male professions are becoming increasing female-dominated. In a study on occupational feminization and pay, researchers found that when controlling for skill and education, professions with more women pay less than those with less women. This is seen in recreation, design, housekeeping, and biology. The reverse happened in computer science; when men started flocking to the field, salaries rose significantly. These changes in pay can be partially attributed to the devaluation of work done by women, a result not of temporal flexibility, but of creeping gender bias. Tangible solutions to the devaluation of women’s work lie in creating structural, systematic change, which would be a huge undertaking for the United States.

One area with huge practical potential to decrease the gender pay gap for everyone is the U.S. school systems. Primary education is an enormous hindrance on working parents, especially in the case of mothers who disproportionately handle childcare. It’s also a huge handicap for working single-mothers and other non-traditional working caregivers. Primary education reforms can reduce the amount of temporal flexibility that working women need.

Take, for example, Germany, which ranked 13th best in global gender pay in 2016 (the U.S. ranked 45th out of 144 countries). Kerri Shigo, former senior marketing manager at Microsoft, moved to Munich with her husband and four children in 2008. Shigo had previously worked part-time at Microsoft to take care of her children. Upon moving to Germany, she took a long-term break from working. In conversation, Shigo expressed that she regretted quitting work for the years that she lived abroad. A large factor that led to this regret was the pre- and primary-schooling in Germany. Her youngest child attended kindergarten, Germany’s version of pubic preschool, from age three to six. The kindergarten school week ran Monday through Friday, and days lasted from 8:00 am until 4:00 pm. Kindergarten school days are set-up so that mothers who need to drop-off and pick-up their children can still work a full eight-hour workday. Another benefit of the German school system is its calendar year, which runs on a somewhat year-round schedule; students are in class for two months, then they have a break that alternates between one and two weeks. Working mothers don’t have to worry about arranging flexibility of timing at work to care for their children during a lengthy summer vacation. Instead, their holidays align more closely with their children’s, so they can use their paid vacation for the other breaks.

Germany’s public-school system is supportive of reducing the amount of temporal flexibility that working moms need, effectively contributing to its smaller gender pay gap. It would be beneficial for the United States to reform its education system, borrowing from some of Germany’s ways. Lowering the age in which children start school would allow working-mothers to return to their jobs after childbirth earlier, if they choose to do so. Shifting the school day to more accurately reflect the work day could allow women to work on their companies’ hours instead of their own. Lastly, reforming scheduling of the school year to eliminate a lengthy summer break and instead have shorter breaks more reflective of the holidays would let mothers better align their paid time off with their children’s breaks.

There are several other approaches and combinations of approaches that would be effective in reducing the U.S. gender pay gap. One such is politics, which is currently at play in Canada, where a cabinet member is pregnant. It’ll be interesting to see how Canada decides to handle its first political pregnancy, and if they use policy change to address it. Other potential solutions are offering paternity leave, uprooting recruiting practices, or improving performance reviews and feedback. Education is merely one route to take in diminishing the U.S. gender pay gap. What is most important is that the causes of the disparity become more widely known, so that more action can be taken to help mitigate the already shrinking gender pay gap.

APPENDIX A

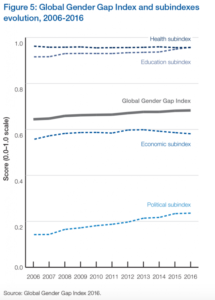

This graph, from the World Economic Forum, highlights the Global Gender Gap Index in contrast to its four subindexes, which determine its value. A Y-Axis value of zero equals inequality, and an X-Axis value of one equals equality. The Education Subindex is much higher than the Economic Subindex, as illustrated by the current environment in the United States—more women are in college than men, yet they are still earning less in their post-graduate careers. This difference indicates a need for a higher Economic Subindex to raise the Global Gender Gap Index.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.