It’s an idea that makes sense for many reasons, mostly notably because it doesn’t toy with our environment quite like gas does. But, as with most change that occurs in this world, the full-on switch to electric vehicles (EVs) continues to take some time.

Many believe that electric vehicles will overtake gas-powered ones in a matter of years. When will this be the case? In order to answer this question, you need to have a basic understanding of what owning and selling an EV requires right now. And this knowledge will give you a solid perspective of the pros and cons of the EV’s existence.

According to PBS.org, Robert Anderson, a Scottish inventor, was the first person recorded to make headway into creating an electric-powered vehicle from 1832-1839. In 1891, a chemist from Iowa named William Morrison built the first electrical automobile in the United States. So the notion of electric vehicles was born far before the emergence of modern technology we’ve come to know.

Still, a column from Business Insider noted that about 34 million vehicles were sold over the past two years in the United States, and mostly all of them were fueled by gas. One of the biggest reasons why people see no need to shift from gas-powered to electric cars is due to the time length of charging a battery.

It takes a short matter of minutes to refuel a gas-powered engine, while most electric vehicles need to be powered overnight or take roughly an hour at a commercial station, via The New York Times. This reality contributes to an anxiety that if the car’s battery runs out, and you don’t have a charging station nearby, you can no longer travel.

The way to get rid of that fear is to think of EVs like ChargePoint chief executive Pasquale Romano.

“Electric vehicles are more like horses than gasoline cars,” Romano said, also via that NY Times piece. “You refuel them when you’re doing something else.”

The charging options for your electric vehicle are broken down into two levels. Level 1 charging means that it plugs into a typical house outlet. Using the Nissan Leaf as our primary example, it would take 22 hours for a full charge. But driving 40 miles per day, which is typical of the average American, would allow for around nine hours to completely recharge your battery for the next day, per PlugInAmerican.org.

The fact that electric cars are very functional within shorter distances enables them to be used by modern car-sharing technologies like Uber and Zipcar.

“Electric cars on their own may not add up to much,” David Eyton, head of technology at London-based oil giant BP Plc, said in an interview. “But when you add in car sharing, ride pooling, the numbers can get significantly greater.”

Since for many people time is money, you may want to explore other charging methods if a trip were longer, perhaps around 200 miles. The DC Fast Charger costs up about $100,000 and adds 40 miles per every 10 minutes — a dramatically reduced time from Level 1 charging. CleanTechnica.com notes the the cost of a Level 2 charging station ranges from $500-$1,000 — a manageable price— but is less powerful than the DC Fast Charger.

As one could gage, based on the lack of quick chargeable modes, current electric vehicles don’t have the capacity to make long road trips possible. Driving from Los Angeles to the lower edge of Colorado is about an 800-mile journey, and an electric vehicle would make that voyage difficult. This excursion is hard due to, not only the time it takes for charging the battery, but also the amount of charging stations available.

Charging stations aren’t readily available to everyone in the United States, as building this infrastructure is one of the challenges electric vehicle producers face. The U.S. Department of Energy recorded that there are 16,838 electric stations with 44,753 charging outlets in the country. Looking at the map they provide as to where these stations are located, it’s clear and understandable that the east coast and west coasts of the United States are more densely populated than areas like Montana, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Nevada and Mexico. When these regions are rife with charging centers, you’d expect the demand for EVs would also be higher.

When one looks at how the demand of a good or product can increase, price/cost and quality become key factors in predicting demand. Quality seems to be directly correlated to overall cost. Typically, someone will pay less for a good or service they deem of lesser quality. The same applies for the reverse logic: someone will pay more for a good or service they deem of higher quality.

This idea brings into play the possibility that electric cars will, at some point in time, be considered more logical to buy than gas-driven cars, since EVs will be of similar or better quality than their counterparts and also cost less. A report from the Rocky Mountain Institute specified that there are 15 EV models under $30,000 with multiple models that have batteries lasting up to 200 miles. Cars with internal combustion engines can seem a bit more logical with these current numbers, especially if you’re traveling long distances.

But it’s worthy to say electric cars are on their way to becoming cheaper. A new report from Cowen & Co. details that electric cars will be cheaper than their gas partners by the early- to mid-2020s, due to falling battery prices and costs that traditional car makers will deal with to ensure their vehicles abide by fuel-efficiency standards. President Barack Obama enacted these standards in 2012 to strengthen the pull toward the cleaner energy of electric cars, and at the time, dissenters existed.

“The president tells voters that his regulations will save them thousands of dollars at the pump,” Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said in 2012, “but always forgets to mention that the savings will be wiped out by having to pay thousands of dollars more upfront for unproven technology that they may not even want.”

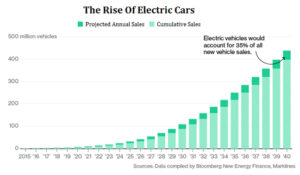

When the cheapness and functionality is clearly accelerating past gas-fueled cars, it will then be up to producers of EVs to make sure supply is on the right level to meet increased demand.

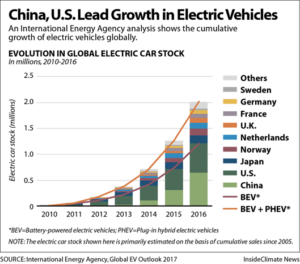

Right now, even though electric vehicles make up for 1 percent of total car sales, the sales of EVs have been growing. Forbes stated that EV sales increased by 36 percent in 2016 from 2015, and have went up at a yearly growth rate of 32 percent over the recent five years.

This rate is primed to grow more and more, as the world becomes more comfortable with phasing out vehicles with internal combustion engines. CNN listed the countries that were planning to completely rid their economies of gas-powered vehicles. France and Britain announced that they would ban sales of gasoline and diesel cars by 2040. India is aiming to get rid of them by 2030. And Norway wants new passenger cars and vans sold in 2025 to all be electric.

China is one of the leading pioneers in the development of vehicles using clean energy. By 2025, states The New York Times, Beijing hopes for one out of every five cars sold to utilize alternative fuel.

The issue facing EV manufacturers in the U.S. now, according to auto sales and information site Edmunds, is that once government subsidies for buyers run out, the market for EVs could crash. This line of thinking is partially based off how Georgia accounted for 17 percent of U.S. EV sales before it dropped to 2 percent after its $5,000 tax credit was eliminated. But states like California, spending $449 million over seven years on doling out these payments, are thinking of spending even more money, $3 billion according to the Los Angeles Times. This move could raise state deductions for EVs from around $2,500 to about $10,000, making a Chevrolet Bolt EV around the same price as a gas-fueled Honda Civic.

The incentives don’t end there, though, as energy company Ovo has devised a way to offset some of the electric cost applied when charging your vehicle at home.

“It provides an economic benefit for electric vehicle owners,” Ovo CEO Stephen Fitzpatrick said. “So they get more use of out of the vehicle that they’ve got parked in the driveway.

When rates for electricity are low during hours of overall less electricity use, the charger by Ovo will fill up the car’s battery. When the rates are higher, the battery would start charging someone’s home or sell the energy back to the grid. One could sell energy back to the grid for up to 25 cents at peak time, while electricity costs about 5 cents a kilowatt-hour during “off-peak” hours.

“In other words, the value of the electricity that’s stored in the battery goes up by a factor of five,” Fitzpatrick said.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.