On May 16, the world’s largest democracy is expected to announce its election results. The ongoing Indian election, which began on April 7, will see more than a 100 million newly eligible voters go to the polls to make an Indian electoral population of 814.5 million. The country’s elections have long been seen as an exercise in political opportunism, voting by personality over party platform and marred by false promises of handouts and subsidies. But this election year, the subcontinent’s 16th since independence, is shaping out to be dramatically different. Faced with slowing GDP growth, dysfunctionally inefficient bureaucracy, and the fading of India’s ‘economic miracle,’ the candidates’ economic posturing is more relevant than ever. To Indians and foreign investors alike, the results of the election and the ensuing government coalition’s make up is sure to usher in a new chapter in India’s economic story.

Rahul Gandhi is the youthful icon of the ruling Indian National Congress party

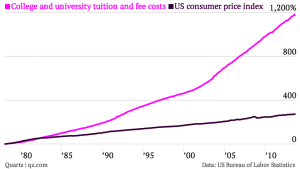

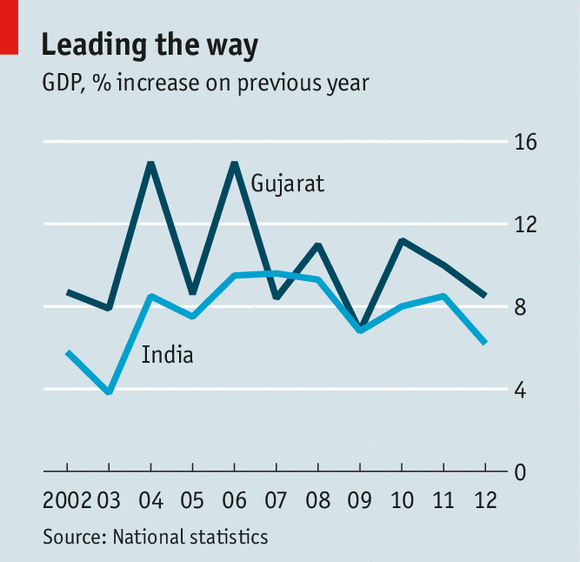

Despite its massive size, the Indian candidature is not as complex as one might expect. Since India’s 1947 independence from British rule, the centre-left Indian National Congress (INC) has dominated the political landscape. Fronting the ruling Congress Party this election is Rahul Gandhi, the promising and youthful graft of one of India’s most distinguished families – which itself includes three former Prime Ministers. On the other side is one of the year’s most talked-about political figures: Nahendra Modi. The self-made leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is known for his 12-year success story in the North-Western state of Gujarat. Since Modi took office as Chief Minister in 2002, the state’s GDP growth rate has been almost double that of its national counterpart (See Figure I). It’s no wonder then that despite Modi’s controversial past (he has been broadly associated with the death of 1000 people, many of whom were minority muslims, in a 2002 riot), much of the Indian electorate is tapping him as their next leader.

Chief Minister Modi of Gujarat and the BJP party are said to be leading the vote

Figure I

Since its 2004 election, the ruling Congress party has developed a rotten reputation for its economic management. Throughout the 2000s the party had reason to be proud, enjoying the effects of the INC’s major economic reforms enacted during the 1990s that paved the way for India’s growth spurt. Riding high on economic success, many in India and abroad were prepared to look the other way. But as the country’s economic miracle has all-but ground to a halt, the party’s shortcomings have been pulled into focus. Critics of the ruling INC have abundantly pointed to the party’s political infighting, corruption, and inability to overcome congressional gridlock as a major cause of India’s inaccessible business climate and, by extension, its economic lag. Indeed, India ranks 199th on the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom and an equally high 132nd on the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business’ list. Similarly staggering, businesses both foreign and domestic must obtain as many as 70 certifications to operate in India.

Unsurprisingly, Modi and the BJP’s realignment from a vehicle of Hindu nationalist agenda to a pro-business, growth-oriented, hardline driver of economic freedom has resounded amongst businesses and investors alike. Indeed, in contrast to Manmohan Singh’s manner of rule, which has been mostly weak and sluggish, Modi’s is decisive, fast-paced, and transparent. Indeed, as Edward Luce points out writing for the Financial Times, “files rarely gather dust in Gujarat. Investments get swiftly approved. Projects are executed on time. And bribes are rare. Gujarat continues to outpace most of India in terms of its investment flows and per capita income growth.”

Modi and his fellow policymakers hope to employ the Chief Minister’s economic model for success, which has been hailed and praised in Gujarat, to revitalise the Indian economy and attract more foreign direct investment. Internally, Modi hopes to restructure the government by reducing its current entanglement in business and cracking down on corruption. But seeing as a even the soundest BJP win these elections will result in a coalition government that must reach agreement in both the lower and upper houses of parliament, Modi is sure to face stiff opposition. On an external and national basis, Modi’s manifesto is one of urban development and infrastructural improvement. Echoing a showpiece project taking place in Gujarat, Modi hopes to transform rural villages into ‘smart cities’ that reduce the strain on current cities and drive up employment and economic growth. Modi’s mix of public spending to incentivise private investment is something that has so far been unachievable under India’s current government.

Nevertheless, for Indian’s both at home and abroad Modi’s economic freedom platform holds a lot of promise. Though the details of its execution remain scarce, there appears to be significant confidence in the marketplace. Compared to the gloomy economic mood just a few months ago caused by high inflation, stagnant GDP growth at less than 5% and major capital outflows, the Indian economic climate has calmed. An increasing number of India’s intellectuals, economists, and elites have thrown their support behind Modi and the BJP. Bloomberg’s Businessweek recently linked market optimism to an economic phenomenon named the “Modi bounce.” Finally, some of India’s more positive economic outlook may stem from the actions of the Federal Reserve Bank of India’s newly appointed central banker, Raghuram Rajan. Rajan has received much acclaim for the RBI’s successful regaining of investor confidence and recovery from last year’s financial instability caused by capital flight.

Raghuram Rajan, the current Governor of the Reserve Bank of India

What Modi and BJP will accomplish remains very much to be seen. While the tune of the party’s agenda is clear, its finer notes remain unclear. But despite the ambiguity, Modi and BJP’s platform brings forth a decisive and confident action that has been unheard of India as of recent, leaving the markets and most Indian investors optimistic. From a non-economic standpoint however, both Modi and the BJP have questionable origins that certainly give voters pause. But whatever the final verdict, you can be sure that Modi’s India will represent something drastically different.