It’s five o’clock on a Friday in Downtown Los Angeles circa 1995. Bankers and businessman check their watches, walk down to their cars, and drive off to their respective homes or apartments throughout Los Angeles. This was the picture of what downtown used to be, a ghost town with vacant offices and a bleak economic outlook for the neighborhood.

Thanks to the emergence of the Staples Center, downtown is no longer the ghost town it used to be. In the past 15 years the neighborhood of downtown Los Angeles has seen a dramatic rise in the number of businesses that have decided to open up shop . But what is driving this dramatic rise?

Many experts believe the growth was buoyed because of AEG’s Staples Center, which is true, but there are several other factors that were just as effective. For example, the creation of Metro Rail, which brought people from Pasadena into this neighborhood, furthering economic activity. Another factor was the completion of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003. There were many roadblocks from 1987 to 2003, but the necessary funds were collected, and it has brought a world-class architecture project to downtown. So we see an amalgamation of investment through private, public, and philanthropic means along with a coincidence of good timing.

The reason why the Staples Center garners much of the praise for this revitalization is because this multi-purpose stadium hosts over 250 events and around 4 million visitors a year, an outstanding number of people to see the revitalized downtown neighborhood. Now, with the construction of LA Live, there are many pull factors like restaurants and bars that see visitors of the Staples Center come early for the event and stay once the event is over. Before the completion of the arena, downtown was best known for the juxtaposition of skid row and financial businesses. In the early 1990’s, banks located in downtown began to consolidate and merge their offices, thus creating empty office buildings and spaces throughout the neighborhood.

Los Angeles is a city that, despite the economic woes of its state, can be seen as a beacon of hope with a global interest that has seen investment from several Chinese firms as well as Korean Airlines. This sentiment has become increasingly more evident with the construction of the Wilshire Grand building that is owned by Korean Airlines. The Wilshire Grand building will become the eighth largest building in the United States, once completed. Generally speaking, the more skyscrapers and construction cranes a city has, the healthier their economy is. That is not always true, but in this case it demonstrates that Los Angeles, and the booming downtown, want to compete on a global scale. Sure, the rebuilding of the downtown neighborhood has been a slow process since the late 1990’s, however, according to Nate Berg, “many in the city are hopeful that the Wilshire Grand is part of a new wave of investment downtown that will help the city compete internationally” (Nate Berg, The Guardian). It seems as though Nate’s sentiments are justified in terms of the investments being brought to the neighborhood, when there are plans for chains like Whole Foods, retailers like Urban Outfitters, and several local restaurants who have decided to expand to the downtown area.

In order to put the rise of downtown in context of, towards the end of 2013, “Six parking lots in downtown Los Angeles recently sold for $82 million” according to Dawn Wotapka of the Wall Street Journal. A staggering amount of money for some parking lots that have plans to be turned into an apartment complex. This is just one deal of many that have transpired over the past 15 years, and the figures seem to keep rising.

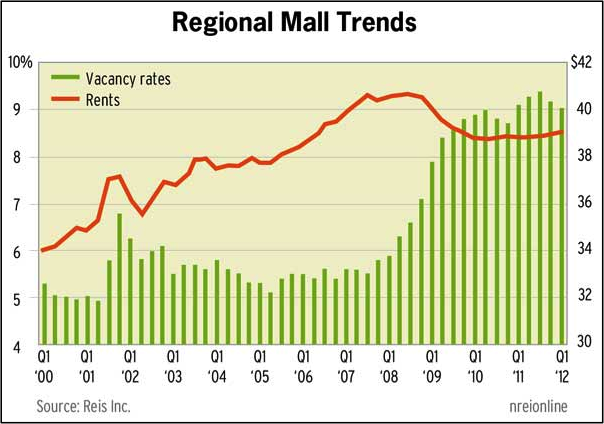

However, the other side of this story is the issue with occupancy rates, and whether or not there are too few apartments or too many people. Wotapka reports, “With more people flocking downtown, the vacancy rate for apartments has fallen. In the third quarter, downtown Los Angeles had a vacancy rate of 3%, down from 3.3%” Along with the dropping vacancy rates in downtown, which means in increase in demand, the consequence is that the average price of rent jumped almost 4% in the final quarter of 2013.

To shed more light and data on the rise of housing in downtown, Wotanka found, “There are about 14,000 apartment units in downtown Los Angeles. About 5,100 units are under construction, and more than 3,400 units were built between 2008 and 2013, according to Polaris Pacific, a real-estate sales, marketing and research firm. More than 3,000 additional rental units have been approved, with another 7,000 proposed. Meanwhile, there are only 17 condo units for sale and 68 under construction.”

Although there are some concerns that there has been such a vast amount of investment for housing downtown that we could see a drop in prices, the consensus among real-estate executives is that the demand will still stay fairly constant and strong. This prediction is justified by a recent report on the diminishing availability of apartment buildings and the relationship with rent prices. Since 2010, rent in the downtown neighborhood has increased by 18.2% and is still predicted to grow because of the strong demand.

There has been a rush of residents flocking downtown, but that does not mean that it was equipped with the necessary provisions of a typical neighborhood.Another major indicator of the downtown area boom, although it may seem trivial at first glance, is the addition of Whole Foods to the flourishing neighborhood. The development of a Whole Foods in downtown serves not only high-priced, fair trade organic groceries, but as a symbol of the seriousness of downtown as a vital area in Los Angeles. As David Pierson of the Los Angeles Times reports, is “a major development in the neighborhood’s gentrification efforts.” He is not the only one praising the development of the high end grocery store. City Councilman Jose Huizar recently stated, “Downtown Los Angeles is like a city within the city that needs a diverse range of services – including grocery stores,” Huizar said in a statement. “Bringing Whole Foods Market to downtown is long-awaited news that represents a major coup.”

But Whole Foods is not the only successful chain that has chosen to explore the downtown area. The recently remodeled United Artists Building, now called the hip Ace Hotel, provides another example of what downtown has become. With locations in London, New York, and Panama, to name a few, the expansion to the downtown area exemplifies the “hip” and “young” vibe that the area now exudes.

Downtown has made tremendous strides and has overcome many obstacles to get the state that it is in today, and many real estate executives believe that the best has yet to come for this burgeoning neighborhood. With rising rents and diminishing vacancy rates, an interesting few years are expected to come in the housing market, with several apartment complexes to be completed. However, in retrospect, you have to look back to the addition of the Staples Center, the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the completion of LA Metro rail lines into downtown, and the subsequent development of L.A. Live as the genesis of this downtown explosion.

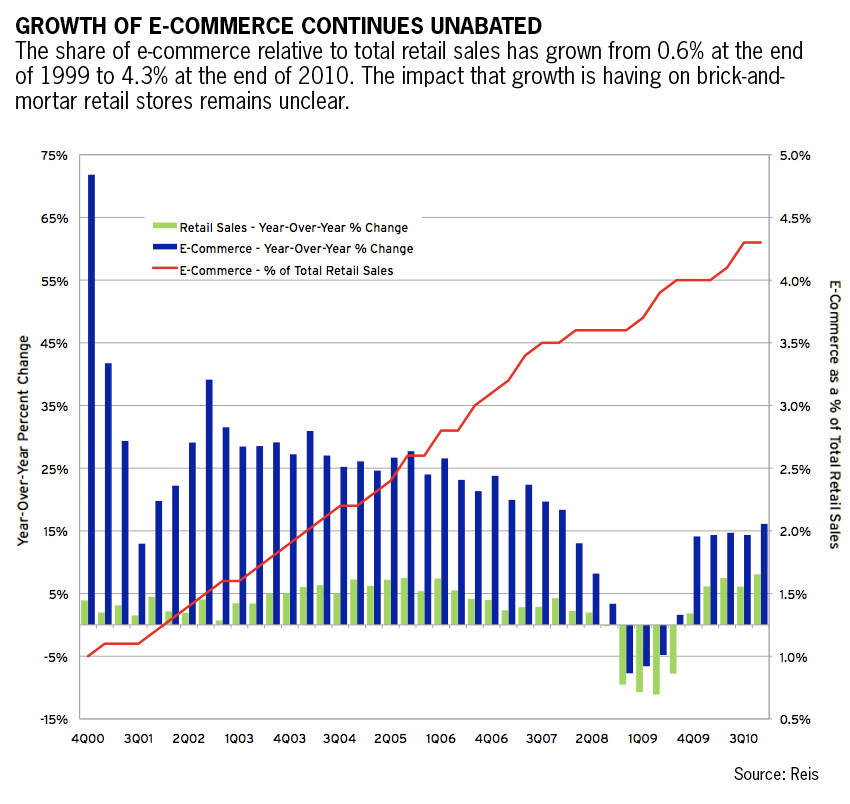

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.