Recently, the Trump administration decided to pay subsidies to farmers to offset the impact of the trade war between the United States and other countries. A similar government intervention policy called “government cheese” had been used during the 1970s by President Jimmy Carter.

All these cheesy stories started in 1949. When the Agricultural Act of 1949 got passed, the U.S. government established the Commodity Credit Corporation to take charge of stabilizing farmers’ incomes. It was the first time for the government to purchase dairy products like milk and cheese from farmers.

In the later 1970s, The U.S. federal government distributed 300 million pounds of government cheese, an almost neon orange mixed cheese, to do food charities. This kind of cheese was five pounds per block, had a rectangular shape, and attached lots of USDA stamps. The primary purpose was to maintain the price of daily supplies. President Jimmy Carter, along with Congress, raised the price of milk 6 cents per gallon and kept increasing the price with inflation in 1977. Also, the government put $2 billion subsidies to save the dairy food industry. Although this strategy saved the dairy food industry from its shortage, the government itself became the primary customer. It bought all the milk that couldn’t be sold by farmers and processed the milk into cheese. Without the market, the government had to store all the cheese in thousands of warehouses and even some caves in 35 states.

“Probably the cheapest and most practical thing to would be to dump it in the ocean,” a USDA official said in 1981. Although the government cheese was useless for the USDA, most Americans at that time still suffered from the after-effects of the recession. Therefore, American citizens harshly criticized President Ronald Reagan and the federal government for the waste of these daily food products, which include cheese, butter, and milk powder.

Surprisingly, Agriculture Secretary John R. Block showed up at a White House event with some pieces of government cheese on his hand and said, “we can’t find a market for it, we can’t sell it, and we’re looking to trying to give some of it away.”

To distinguish the government cheese from regular cheese products, the Commodity Credit Corporation established some new supporting programs to deliver the cheese to lower-class families. One joke related to this was that if you give cheese to people who cannot afford regular cheese, it is not a behavior to hurt the current market. Obviously, it is not true. This government cheese story has shown the butterfly effect of one government intervention. Ultimately, the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program released more than 30 million pounds of cheese around the nation.

When the dairy prices came down in the 1990s, the government finally took itself out of this “cheese charity” business.

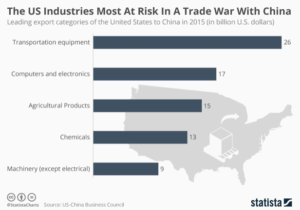

However, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture secretary Sonny Perdue announced the plan to provide $11 billion subsidies to assist the farmers who had struggled during the Trade War, the same organization Commodity Credit Corporation comes back and start to do its job again.

Sources:

https://www.history.com/news/government-cheese-dairy-farmers-reagan

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/07/645459818/government-cheese-well-intentioned-program-goes-off-the-rails