New Year’s Day is always special, but for Finland in 2002, the day was very, very special. In the afternoon, I walked across Esplanade Park in Helsinki heading to a restaurant and stopped by on an ATM to withdraw money.

The cash machine did not give me Finnish marks, as it would have done the day before, but pumped out euro notes.

My home country had a new currency. I was holding my first euros in my hands.

Euro had come into existence virtually on January 1, 1999, and now, two years later, notes and coins started to circulate. Eleven EU countries took part in common currency’s first phase, and Finland was one of them – alone in Northern Europe.

I was an undergraduate student and did not have much on my bank account but I was thrilled about the euro. I no longer needed to exchange money when travelling to Central Europe. I bemoaned euro hadn’t been there already year before when I spent an exchange semester in a journalism school in Brussels.

I thought my Swedish and Danish friends were so unlucky not to be part of the joy. Their countrymen had rejected euro membership in referendums and they still had their boring crones.

I considered very carefully how much Finnish marks I would save for the future as a reminder of the “old times”. People said that some day marks could be considered rare items of collection. Would I want to give marks to my children some day?

The dual circulation period lasted two months, and at the end of February 2002, I put some mark notes and coins to an envelope. Shops no longer accepted them. I solemnly thought they were for the future generations.

I couldn’t have guessed that just 15 years later there would be serious talks about getting marks back as our currency, as soon as possible.

No one is celebrating euro anymore. It is now the common currency in 19 out of 28 EU countries and used by nearly 340 million people every day – and it has become a synonym of a crisis.

In 2015, Finland’s economy is in recession nearly for the fourth consecutive year, and many blame euro.

The former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Paavo Väyrynen, is one of the loudest critics. Last summer the stubborn old statesman started collecting signatures for a petition to get Finland’s departure of euro membership before the Finnish parliament.

I have no idea where my envelope of old Finnish marks has gotten. Should I start looking for it?

Could I possibly use them one day?

Paavo Väyrynen, at present a member of the European parliament, says that with the petition he is doing what is necessary. With its own currency, Finland could reign its own monetary policy and devalue.

Finns remember what devaluation means, as it solved the country’s most severe peacetime crisis in 1993. Economy overheated largely due to a change in the banking laws in 1986.

Eventually Finland let mark float and adjustment mechanisms worked. More competitive exchange rates enabled the country sell its products at a cheaper price.

Väyrynen was elected into Finnish parliament for the first time in 1970, and he’s served in eight cabinet of ministers of Finland. He’s now got over 50,000 signatures on the petition which means Finnish parliament might to have a look at the issue. Väyrynen wants the parliament to debate whether the country should exit eurozone and to enact a law that would make “Fixit” – Finland’s euro exit – possible.

In his opinion, the elite of the country cannot admit they made a mistake.

”Elite does not want this topic even to be discussed,” Väyrynen wrote me.

I asked him why did he decide to collect signatures – and what are his party colleagues thinking of it. Väyrynen’s party Keskusta – The Center – is Finland’s prime minister party at the very moment, and Prime Minister Juha Sipilä is not criticizing euro at all – on the contrary.

Väyrynen answered me saying he is sure his petition will proceed into the parliament and as he no longer has official status in Finland he feels the petition is justified as a method of exercise of power.

Väyrynen has objected euro and Finland entering the eurozone from the beginning. His party was eurosceptic but as soon as it won the election last spring, the ones in power have committed themselves to the common currency. The official stand is that euro brings “stability”.

Väyrynen says that half of his party does not believe in that but the others remain silent.

On December 10, 2015, the governor of the Bank of Finland, Erkki Liikanen, held a press conference about the economic situation of Finland. I watched it online (here: http://cloud.magneetto.com/suomenpankki/2015_1210_liikanen/angular). It was a very monotonous talk for which Liikanen had given a very dry and long title. The translation into English would be something like: “About economics, monetary policy and financial stability in Finland. Ten year’s economic development 2007-2017 from five different perspectives.”

I was anyway curious to find out what Liikanen’s five perspectives were, as other experts seemed to have just one viewpoint. The economy of Finland is miserable, no matter where you look at it.

In the third quarter of this year, Finland’s economy contracted by 0.6 percent. Odds are that this year will end up being the country’s fourth consecutive year of recession.

There are – for now – some nice numbers and qualifications related to Finnish economy: rating AAA- of sovereign debt. Quite moderate 62 percent government debt-to-GDP ratio. Ranking among the top ten most competitive economies in the world by the World Economic Forum.

But these don’t seem to help (and the last one, in my opinion, has to be a miscalculation).

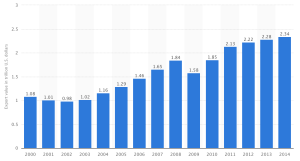

Finland’s debt-to-GDP ratio is now nine percent bigger than in 2007. The Bank of Finland estimates it to grow from present 62 percent to 68 percent by 2017.

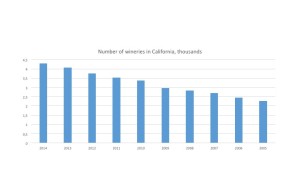

Between 2008 and 2014 Finnish exports shrunk by 12 percent.

This is why country’s Prime Minister Sipilä’s goal is to bring about internal devaluation as quickly as possible. The former businessman has been in power since the spring 2015 and has shaken the Finnish political culture. He is ruling like a CEO, not like a negotiator. He is determined to get the labor costs down in spite of the trade unions’ strong objection.

He believes in austerity, as does the governor of the Bank of Finland Erkki Liikanen.

In the press conference Liikanen offered five familiar explanations to Finland’s state, no fresh viewpoints.

Finland’s overall production is in a downturn because both productivity and the amount of workers are decreasing.

The age structure of Finland is a disaster. According to the Bank of Finland’s estimate, in 2017, there will be 200,000 more pensioners, 50,000 more unemployed, 5,000 more under 15-year-olds and 50,000 less workers than in 2007.

In the third quarter of 2015, the value of exports was 19 percent smaller than in the second quarter of 2008, which was the best economic quarter of 2000s in Finland. ”No other developed country has seen this big decline in exports during these years,” Liikanen said and reminded us that Finland’s eastern neighbor Russia, the main export market, is in a ”deteriorating economic state”.

Bank of Finland estimates that between 2007 and 2017 the debt to GDP ratio will raise from 53 percent to 68 percent. The same time the deficit in the whole eurozone is about to decrease by two percent in the average.

Because pensioners and unemployed now bring more costs, the government of Finland has less to spend on other areas. In 2007, money spent on pensions was 29 percent of country’s budget. In 2017, it will be 32 percent.

”Actions are necessary,” Liikanen said in the end, not surprisingly.

Necessary actions, according to Liikanen, include improving cost competitiveness and restructuring the pension system and social security system. People should a have more active work years in their lives, he continued.

”Electronic and forest industry are highly cost competitive areas of business.”

Electronic industry have suffered from Nokia’s collapse. It used to be the biggest employer of Finland and played a major role in exports. Forest industry is still the basis of Finland’s exports. But:

”Salaries have risen more than in the eurozone on average, and at the same time, Finnish companies’ ability to pay salaries have gotten worse. Companies must be able to offer their products overseas with competitive prices,” Liikanen said in his laconic style.

He added that Finland needs less regulation and more competition. He undoubtedly meant that trade unions have too much much power. Finland is ranked 103rd out of 144 countries for labor flexibility in 2015 by the World Economic Forum.

”When there are new entrepreneurs, there is more competition and thus more innovations,” Liikanen said.

As the Governor of the Bank of Finland Liikanen is also a member of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank and a Governor of the International Monetary Fund for Finland.

He has strong ties to European Union’s institutions. In 1990, he became the first Finnish ambassador to the European Union and in 1994 he became the first Finnish Member of the European Commission. He was Commissioner for Budget, Personnel and Administration.

I wouldn’t expect him to critisize euro. But I would have expected him to talk more about ECB:s monetary policy.

All he said was: ”Monetary policy is already supporting the recovery of national economics but as the interest rates are low, we must take care that negative side effects do not occur. So macroeconomical stability policy is needed.”

Liikanen pointed out that statistics show that Finland has used more mechanisms of finance policy than any other country in eurozone to help its’ economy to recover.

He rejected stimulation by saying:” Because Finland’s problems lie in exports, stimulation is not an answer. The biggest losses are in the industry, whereas the service sector has grown. This is why raising the internal demand by stimulus is not a solution. However, public investments that are likely to accelerate private investments are to be implemented.”

Finland’s largest sector of the economy is services at 65.7 percent. Manufacturing and refining together make up 31.4 percent. Primary production is 2.9 percent.

Journalist Simon Nixon sounded just like the Finnish government on November 25, 2015, when he wrote on Wall Street Journal that “Finland’s Problem Isn’t the Euro”.

”It is easy to exaggerate the role devaluation played in the British and Swedish recoveries”, Nixon wrote.

Sweden has cut its public spending from over 60 percent of GDP in the mid-1990s to just over 50 percent now. Finland’s public spending is at present 59 percent of GDP.

Finland’s working-age population economically active is five percentage points below that in Sweden — “a serious problem for a country whose workforce is already shrinking as a result of having the worst demographic profile in the EU,” Nixon compared.

He reminded his readers that ”two of the fastest-growing economies in the EU now are Ireland and Spain, both of which are in the eurozone.”

And that Finland has benefited from unprecedentedly low funding costs since the start of the euro crisis. ”That reflects Finland’s high levels of fiscal credibility, based on its low debt and deficits and its commitment to complying with the eurozone’s fiscal rules.”

Helena Yli-Renko, Assistant Professor of Clinical Entrepreneurship at University of California, also emphasizes the positive effects euro has had. Common currency has helped Finnish companies to grow global, she said to me. ”Common currency has been a way of simplifying processes.”

Opinions about euro are many and mixed so I asked even more of them.

Unto Hämäläinen is eminent political commentator in Finland and senior editor of the leading newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. He pointed out that, first of all, Paavo Väyrynen has revenge going on with his petition.

Väyrynen is bitter of not getting minister’s post after this year’s elections, after which he decided to stay in The European Parliament and get back at the party’s leader, Prime Minister Sipilä. Väyrynen is an attention seeker, Hämäläinen said.

Hämäläinen in convinced that Fixit won’t happen and is not even discussed about because the two parties that were originally against euro are now the two ruling parties of Finland. In Finnish parliament, there is no party that would support Fixit.

Another journalist, prominent economic writer Paavo J. Teittinen says that he believes Finland would be better off without euro. He himself supports Fixit, but he does not believe mark will ever come back. In Teittinen’s opinion, it’s ridiculous that Finnish politicians blame other countries for not following the euro regulations because the biggest problem in euro is the regulations themselves. Currency it’s not planned well at all.

Euro was just a mission of peace in Europe.

It allowed Finland to position itself in the core of Europe and away from the unpredictable Russia.

Ove the years the ones who have been against euro are the ”foolish conservatives” or the ”provincialists”. The populist right-wing party Perussuomalaiset had the departure of euro in their agenda – until they became a governing party.

Many others are just unrationally attached to euro.

Teittinen hopes that the possibility of the exit would anyway be studied thoroughly and discussed seriously.

We do not want to be in a situation where we face more troubles and ask ourselves silently if they are due to a malfunctioning currency.

I agree.

I will not climb to the attic to look for my envelope full of Finnish marks. Not yet.

Sources also: The Wall Street Journal

Bank of Finland

Helsingin Sanomat

The World Economic Forum.