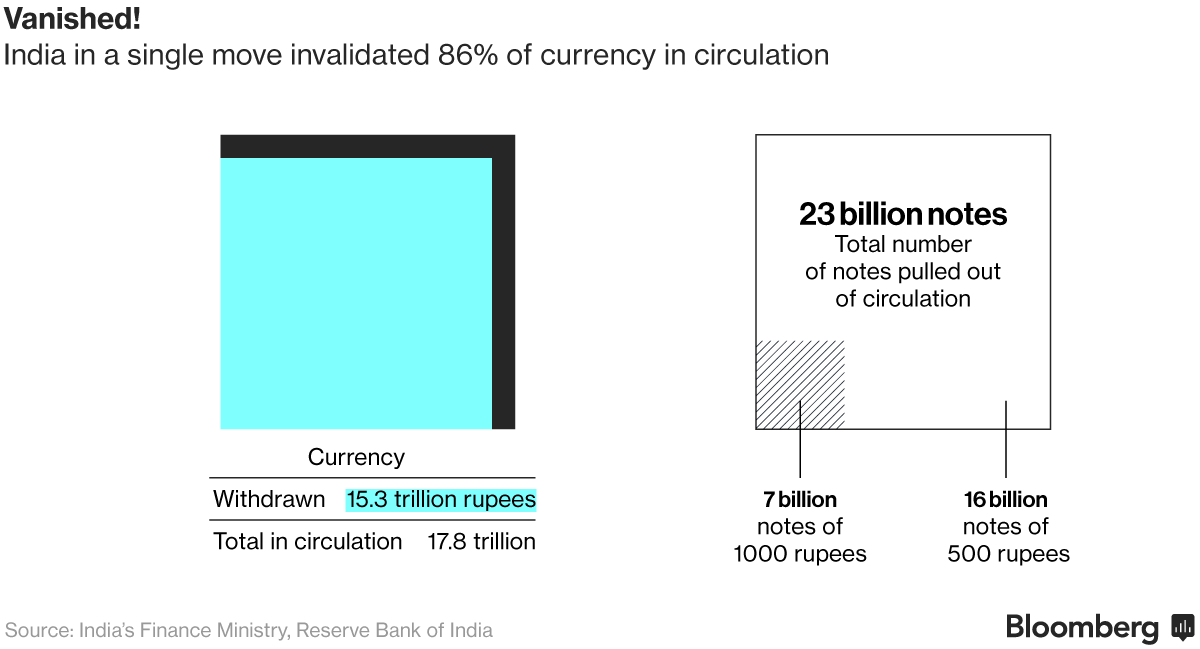

On Nov. 8, the Narendra Modi government surprised India with a declaration banning 500- and 1,000-rupee notes (Rs500 and Rs1, 000) to tackle black money and corruption. The demonetization policy may be well intentioned, but it has brought up unintended consequences over the domestic economy in India.

Rs500 and Rs1, 000 were India’s two biggest notes that and accounted for 86 percent of the money in circulation by value. According to the announcement, all citizens will have until Dec. 30, 2016 to exchange the old banknotes at bank branches. People seeking to replace more than Rs250,000 (about $3,650) must explain why they hold the cash. Those who fail to do so must pay a penalty.

Due to the large number of notes and the short replacement period, Indian banks and ATMs have long queues as people rush to exchange old notes for new ones. The government can’t print enough new notes to fulfill the demand. Till Dec. 10, the banks have received Rs12.4 trillion as deposits but only released Rs4 trillion back into the system as of 5 December.

People queue as they wait to exchange or deposit their old high denomination banknotes in Jammu, India. Photograph: Mukesh Gupta/Reuters

As a normal economy influence, the lack of cash led to a soft inflation on the market. Food inflation in November softened to 2.11 percent from 3.32 percent a month ago, according to data released by the Central Statistics Office. Retail inflation also decreased from 4.2 percent a month ago to 3.63 percent.

However, the demonetization of high-value currency notes has had a negative impact on the Indian economy. The lack of electronic bank accessibility and wireless payment in India has magnified the effect of insufficient cash on the business activities of investors and consumers. The overall industrial output decreased by 1.9 percent compared to before demonetization, according to the industrial production data.

There are worries about the money liquidity problem. “The Reserve Bank of India is likely to outline measures to manage the systemic liquidity, which would be of interest to the banks, and provide some timeframe by which cash liquidity would increase, that would be of significance to the public,” said Naresh Takkar, managing director at ICRA Ltd., the local unit of Moody’s Investors Service.

The original goal for the government’s demonetization policy is to tackle black money — cash that is not declared to avoid taxation or that is obtained via corrupt practices. But according to the New York Times, the vast majority of black money in India isn’t money at all. It’s held in gold and silver, real estate and overseas bank accounts. The requirement also stimulated a new black market where people can break old notes into smaller ones by illegal couriers.

Demonetization alone can’t tackle the issues of black money and corruption. More actions toward improving policies for administration transparency, tax regulation and the modern online bank tracing system are needed.

Work Cited:

India pulled 86% of its cash out of circulation. It’s not going well.

http://www.vox.com/world/2016/11/29/13763070/india-modi-cash-demonetization-protests

Cash-Crisis India Looks Likely to Cut Rates

In India, Black Money Makes for Bad Policy

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/27/opinion/in-india-black-money-makes-for-bad-policy.html

How India’s Cash Chaos Is Shaking Everyone From Families to Banks

New note ban rules and regulations as of 14 December