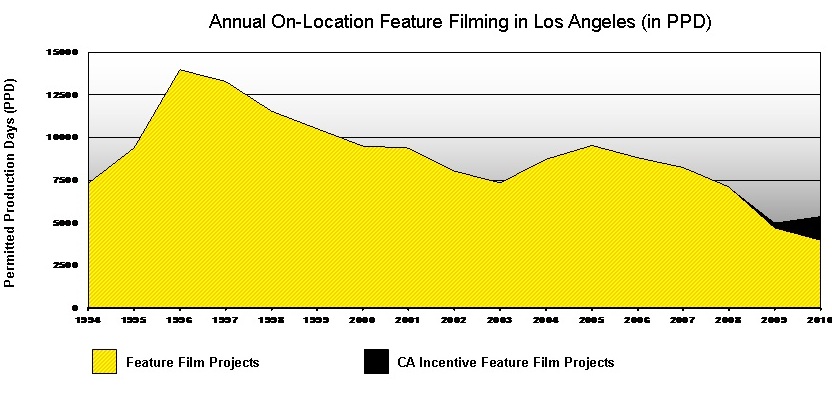

The cable television industry’s costs are increasing while its user base is simultaneously vanishing. “2013 marked the first year in which the paid TV industry actually shrank,” reports USA Today. More and more people are looking to a cable-less future, flagshipped by a trend dubbed “cord-cutting”, while the current generation of millennials will probably exist as something more along the line of “cord-nevers”. However, multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs), including cable television/pay-TV operators like Comcast, satellite operators like DirecTV, and telco companies like Verizon, all rely on the current model and won’t give it up without a fight…a fight finally unified under the banner of: ‘TV Everywhere’.

America easily made the transition from a broadcast- to a cable-nation. An endless array of channels featuring a smorgasbord of programming perfectly suited our appetite for consumption, while also fixing some of the technological issues found with (free) antenna-based broadcasts. In 1996, the Telecommunications Act created the cable industry as we know it by “relaxing regulation on media cross-ownership…to foster competition…[and allow] telephone companies to offer TV service and cable operators to deliver phone service.” This also opened the door to FCC-approved mergers between the big boys of the media industry, resulting in the monopolistic fact that all content creators are controlled by a few major companies: Comcast/GE, Walt Disney, Viacom, CBS, News Corp. [that recently spit out other giant 21st Century Fox], and Time Warner Inc. Several of these companies own local TV stations in key media markets. Comcast is also the largest cable provider in the country, even more so if their attempted acquisition of Time Warner Cable (a separate entity than Time Warner Inc.) is allowed.

As online distribution continues to rise, consumers wouldn’t be faulted in wondering why content creators still kowtow to the Man. The answer will in no way surprise you: money A.K.A big bucks in the form of affiliate fees. Every year, $32 billion flows from the cable companies to content creators in order to grease the machine. “Estimates suggest that the annual affiliate fee revenue at companies like Viacom and Disney is around $1.5 billion and $2.0 billion respectively.” So for content creators, the strategy becomes entirely focused around “profit maximization.” Find a couple hit shows, while keeping the rest of the lineup relatively inexpensive to curb programming costs. “The ‘hits’ make you a ‘must have’ for any cable or satellite carrier – granting you the right to ask for fees.” Content creators want channels balanced at just the right point between costs high enough to give a few shows the production-cost/marketing edge they need, while still keeping the overall schedule cheap enough to reap the benefits of affiliate fees. Why are there so many sports channels? Remember the mantra: “If you own exclusive content, you might as well build a channel around it.” In this way, even with online distribution an option for the content creators, the cable companies still have them hooked on precious affiliate fees.

The case of Hulu is a great example. With stakeholders including Fox, Disney, and NBC Universal, the service was initially a consumer-friendly (read: free) way of streaming their favorite shows whenever they so desired. Nicely personified by Bill Gurley of Above the Crowd, pay-TV distributors smiled nicely at the content creators, while through gritted teeth said, “[w]e pay you an affiliate fee to distribute your content to the homes we serve. We understand you have multiple distribution partners. What we don’t understand is why you would give content to some of them for free, and still expect us to pay our fees…” And like that, Hulu became a subscription-model service itself. Join us or die, says Pay-TV…

Now the rebellion seems to have moved to a grassroots level. The cable bigwigs created the pay-TV model by charging customers a subscription price in exchange for a cable package of channels. Once-reasonable prices have grown with the scope of television, driven by our increasingly cinematic desires. Like the DVD boom fueled the booming budgets of Hollywood, TV scale has increased to the point where millions and millions of dollars can be spent on a single episode of Lost or Game of Thrones. Spectacle is where the eyes drift. Cable companies have also reduced spending in the customer service department, leading to an immense decline in consumer satisfaction, with jokes about Comcast’s lack of reliability just as relatable as the age-old classics like “what’s the deal with airplane food?” While $86 on average in 2011, cable bills are expected to climb as high as $123 by 2015. Addicts, and by that I mean television viewers, have realized they might be taking a ride they wouldn’t actually have to pay such exorbitant costs for elsewhere. So, they cut the cord, and end their subscription to cable. The age of “cord-cutters” and “cord-nevers” began.

Eyes opened when Netflix emerged as an instant streaming titan, alongside video purchase and rental systems like those present on iTunes and Amazon Prime. Combine such services with products like the AppleTV, the Roku, or the new Amazon FireTV, and a hassle-free solution to cable company headaches became clear to a lot of people. Instead of a high cable bill, a one-time purchase of a streaming device opened the door to a still-immense quantity of content. With many cable customers already in possession of a Netflix account, Amazon Prime login, or iTunes videos, it seems the costs ended there, with no messy dealings with Comcast needed. This ‘a la carte’ or ‘over-the-top (OTT)’ model of content consumption already had a popular infrastructure in place, and now quality products popped up to streamline the process further.

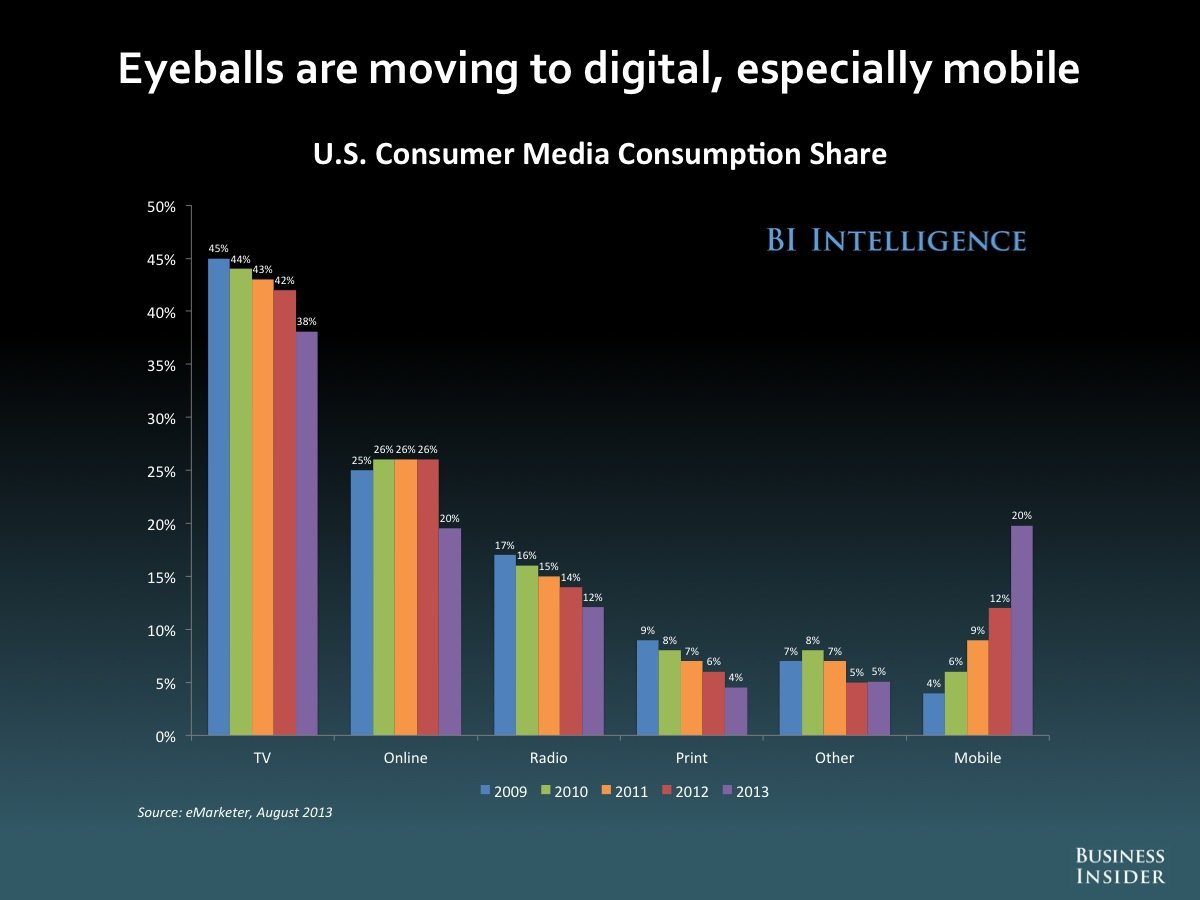

According to Jim Edwards of Business Insider, “1.3 million of [cable distributor] Charter Communications’ 5.5 million customers no longer want TV – only broadband [as of November 2013]…[p]eople are giving up on cable TV as a standalone product.” Fewer households are stocking televisions as a part of their personal American Dream, content to consume media on technology like mobile devices, tablets, and laptops. Instead of plopping down on the couch in front of the tube after a hard day’s work, people instead boot up their electronics, Mom upstairs, Dad in the basement, the kids in their rooms…it’s come to be known as “vampire media,” coming out after dark and sucking away life as the pay-TV industry knew it.

Even antennas are making a comeback, able to offer the Netflix-enabled population sixty channels or so of free broadcast content, in better-than-cable HD, and, if new company Aereo has its way, the ability to record and rewatch free broadcast content on the device of their choosing. In this case, broadcasters claim theft, while Aereo responds it’s only supplying the equipment (“arrays of small antennas – one for every subscriber – to stream over-the-air television signals to its customers”) and not the content.

Many like Aereo have taken up the ‘cord-cutting’ mantle and proclaimed it the future, a weapon to use against the supposedly greedy and inept cable giants. Video for the people, made by the people, distributed by…well, here’s where it gets tricky. Returning to Aereo, the company has found itself before the Supreme Court, its business resting in their hands, while cable calls for blood. The Court finds itself in a tight spot. While it views Aereo’s business as unconstitutional, their ruling’s wording must be very carefully constructed in our digital age – they don’t want to accidentally outlaw the Cloud alongside Aereo. With such a thin line between legal and illegal a distinct possibility, how is cable to combat the rising threat of Silicon-Valley-fueled distribution while keeping consumers firmly in their (certainly not free) corner? Enter Jeff Bewkes, CEO of Time Warner, circa 2008.

Bewkes, who once headed HBO and led it to success, watched as cable’s cultural grasp slowly loosened. He also noticed how HBO was experimenting with an online streaming service, in select Wisconsin cities, where as long as viewers could login as an HBO subscriber (‘authenticate’ their account) they could stream all the HBO they wanted. Bewkes, along with Comcast CEO Brian Roberts, saw such a model could be viable for cable subscriptions as a whole. Thus, TV Everywhere was born.

Bred slowly through systems like Time Warner’s TWCTV and Comcast’s Xfinity TV, TV Everywhere has now been picked up by the Cable & Telecommunications Association for Marketing (CTAM), rebranded in trendy lowercase ‘tv everywhere’, and put forward as cable’s Netflix-generation killer app. CTAM is readying its member companies (including A&E, Discovery, Disney, Time Warner, Comcast, Viacom; 16 cable companies and 25 content providers in full) to advertise all of their diverse subscription/streaming services under the singular new banner in order to promote unity and simplicity. “’The cable industry has been very good at not jumping too early on a technology, and watching it play out first,’ says Colin Gounden of Grail Research, which advises companies on new products. ‘They have a knack for getting the time right.’” CTAM’s goals for the new year have been set in stone by the board of directors, made up of programmers and cable operators from across the spectrum of the partnered companies. The First Commandment of tv everywhere is for half of all cable subscribers to be aware of tv everywhere by the end of 2014, up from about twenty percent now. The Second is to make the half already aware into devoted users.

Bewkes illustrated such a possibility with his battle plan to use viewers’ familiarity with cable’s huge brands and turn their love of streaming against the new independents by restricting digital rights to popular shows. The goal of tv everywhere is “to keep subscribers happy by letting them access cable content wherever they might be. In practice, this means lots and lots of apps,” like HBO Go, FX Now, and Xfinity TV. Comcast’s new X1 box operates very much like a Roku, full of app offerings like Pandora and even video games, but with a full cable subscription stacked on top. CTAM is also betting on the remaining cable figures: 56 million people are still subscribers, on top of their cord-cutting-enabling devices. To Multichannel News, CTAM CEO John Lansing said, “Compared to an $8-per-month over-the-top service, offering past seasons of shows plus some new original series, TVE is ‘all-original, it’s all last night, it’s live streaming [like the recent Olympics and Oscars] and it doesn’t cost you another nickel.” TV Everywhere was ‘broadcasting’ 150 million videos per month as of the end of 2013.

There are those within the industry that criticize CTAM’s label, saying it could distract or confuse consumers when they’re presented with the veritable cornucopia of tv everywhere services, and that it would be more valuable to expend effort improving the content instead. Cord-cutting proponents point to recent contract renewals between cable companies and content, where cable has been forced to loosen up on digital rights to make the increasingly pricey programming costs digestible. That said, controlling distribution is the pump that keeps the affiliate money flowing to the content creators in the first place. Right now, Netflix is profiting from the content owners’ need to reach the eyeballs of America. However, according to USA Today, Disney’s cable expenses soared over $8 billion last year, and “$7.99-per-month Netflix subscriptions are never going to float a ship that big.”

If tv everywhere, as a brand itself, is able to build enough of a reputation, USA Today suggests, “it may be just a matter of time before more of this content is kept in-house and Netflix finds itself stuck with whatever’s left.” Once tv everywhere, silly lowercase spelling or no, evolves into a more coherent form, and content creators settle down and move in, the disruption will end, most likely with a whimper. Remember, the cable companies know how to lie in wait, slowly absorbing technological advances, and then pouncing, armed with their special weapon: billions of dollars. Cord-cutters are right about one thing, at least. Get out your scissors, and cut that connection…but the cable companies have cut ties and migrated to the Clouds, too. The future of media is a big ol’ party, and everyone’s invited. Just remember there’s always got to be a cover charge, and the big guys like to collect. Personally.

Sources: Business Insider, Wall Street Journal, Forbes, New York Times, Above the Crowd by Bill Gurley, Businessweek, USA Today, CNN Money, Multichannel News, CTAM Official site