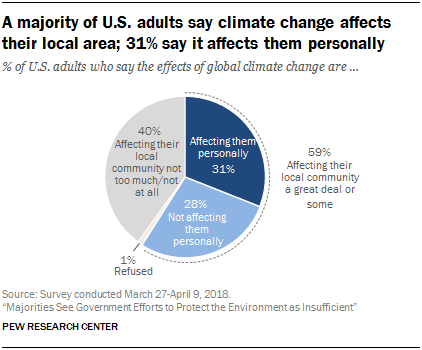

One of the biggest concerns for the current American public is taking action against climate change. In recent years, more people have reported feeling the effects of climate change firsthand than ever before. Around six-in-ten Americans claim that climate change is affecting their local community in either a great deal or at some capacity. This is due in part to increasing global temperatures and rising sea levels effecting both inland and coastal communities.

Those most at risk are often low-income communities. Cheaper housing can be found in high-risk areas such as flood or fire zones as well as in decaying, older housing that can be equally or if not dangerous in a natural disaster. The latter is due to the fact that older housing is often not outfitted with updated building codes that implement fire-proof or flood-mitigating infrastructure. Even the streets themselves may be incapable of handling efficient transport of emergency services. The more likely a firetruck is to get stuck in a congested street, the more likely the building in an old urban district is to face irreparable damage or even get burned down.

It’s no contest that failing to address climate change early has contributed to an increasingly burdensome cost on mitigation efforts. Firefighters are subject to increasingly longer overtime hours, FEMA applications in flood zones have skyrocketed, and local governments, including California and Texas state governments, are looking to buy out housing in high-risk areas to prevent further housing in those regions. The costs are also looking to increase in the next few years.

Many Americans are electing preventative measures to combat climate change. This includes choosing eco-friendly brands who are changing manufacturing practices to reduce carbon emissions to conserving resources including energy and other utilities. This conservation of utilities is also a cost-saving benefit to many households. However, there is a glaring issue in terms of the infrastructure of utilities provided for by both public and private companies that negatively affect low-income households‘ ability to participate in eco-friendly activity and economic conservation: infrastructure.

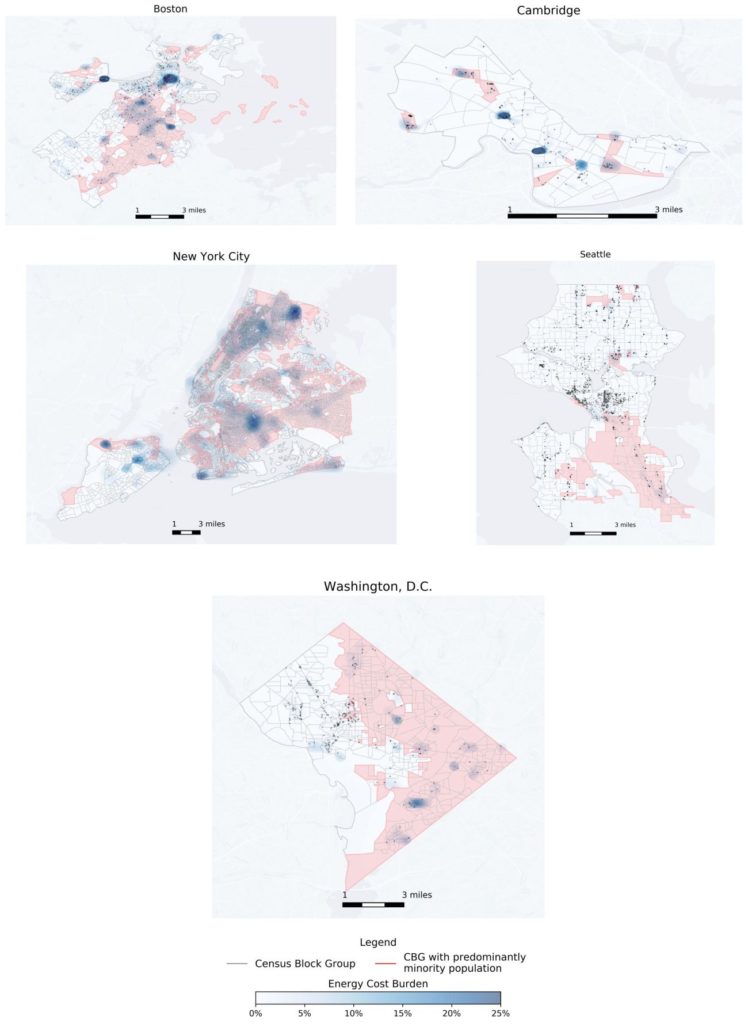

In a study that analyzed socioeconomic status and energy consumption, New York University urban planning researchers Constantine E. Kontokosta and Bartosz Bonczak and the University of Pennsylvania urban planning professor Vincent J. Reina found that the highest consumption was found in both the lowest and highest income neighborhoods in the study.

While the consumption levels for the higher-income bracket is attributed to an average increased use through more appliances, electronics and other behavioral choices, the same could not be said for the low-income bracket’s use.

As stated before, much of low-income housing is often found in regions with aging buildings that fail to upgrade its infrastructural components to fit current standards found in new housing. As a result, new technology that provides more efficient systems in conveying utilities is never implemented. No matter how hard these households attempt to conserve resources on a behavioral level, they ultimately end up using and paying more because of their outdated systems.

The same can be said for subsidized housing units, where often the cheapest option for utility conveyance is placed in rather the most efficient. This leads to small short-term costs at the expense of the developer, but large long-term costs at the expense of the resident, who must outfit the monthly utility bills.

This places an extra burden on low-income households, who already pay an increasingly larger portion of their income on utility bills overall—up to 20 percent of their wages as opposed to wealthy families who pay between 1.5 and 3 percent of their income. Thus, this infrastructural issue is both at a significant cost of low-income communities as well as the environment.

Currently, there is little incentive for private housing units to provide upgrades to their aging structures without placing the expense on their tenants. On the other hand, public housing is beginning to see promise in the form of legislation—particularly the Green New Deal.

The ambitious bill proposes seven different grant programs to completely replace the energy systems of public housing nationwide within 10 years. The replacements would either consist of renewable or sustainably carbon-neutral systems, addressing the issue of aging infrastructure as well as carbon-emission reduction.

While the initiative shows promise, the bill is still in contention in Congress and has yet to be enacted. If we wish to see both alleviation of the burden and stress of low-income living in the nation as well as protecting the most vulnerable population from climate change, more investment on sustainable infrastructure and utilities needs to be made.