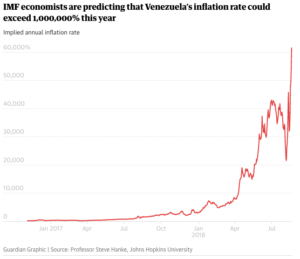

Millions are hungry, ill, and suffering from lack of food and basic necessities such as a police force to patrol the increasing crime in Caracas. In the capital, local residents are constantly rushing to supermarkets and gas stations, waiting in line for hours. Many are even resorting to eating rotten meat. The International Monetary Fund recently declared the lack of stability in the bolivar, predicting Venezuela’s projected inflation rate to be over 1 million percent by the end of 2018. Every day, the foundational pillars of Venezuela’s economy are rapidly changing: the prices of bread, the exchange rate between the US Dollar and the bolivar, and the trust of the Venezuelan people.

How did a prosperous country spiral out of control in less than two decades? It wasn’t always like this. Blessed with the largest oil reserves in the world, Venezuela has had a stable economy based on mostly oil revenue since the 1990s. In fact, they had such immense wealth, with the purchasing power parity (PPP) for GDP per capita was placed just over $16,000 in the 1990s. The economic disaster can be traced back to 1998 when Hugo Chavez was elected President of Venezuela. As he came from a similar background of poverty from the small village of Los Rastrojos in Venezuela, Chavez appealed to the lower-income individuals of Venezuela. After securing these votes, President Chavez was hit with a stroke of luck: a decade-long rise in global oil prices followed his election.

With Chavez in power, Venezuela’s dependence on oil grew— oil accounts for 96% of Venezuela’s exports and over 40% of the government revenue and the rise in global oil prices felt like a jackpot. The flourishing government finances drove Chavez to make a series of economic decisions that tend to be appealing to politicians—good in the short run but disastrous in the long run. Chavez’s socialist regime began to increase spending but as oil revenues declined, they also increased their borrowing. According to the Financial Times, the figure was around $25 billion during 2004 and just last year, the best estimate is around $178 billion. To continue to appeal to the poor, Chavez then spent this new wealth on food subsidies, health care for the poor, and improved education. Although these social programs certainly raised the quality of life for lower-income families, they were unsustainably funded, relying heavily on one major industry—oil. In fact, Chavez did not actively attempt to lay off the dependence Venezuela placed on oil exports. Instead, he zeroed in on welfare programs to the point that his unrestrained spending led to a deficit.

After Chavez died in 2013 and Nicolás Maduro succeeded Chavez as President of Venezuela, the oil prices plummeted in 2014. The U.S. Energy Information Administration states that in June of 2014, crude oil cost $112 per barrel (bbl) and by December, it went down to $59 per barrel. The Venezuelan economy took the hit hard as the GDP shrunk by 30 percent during a four-year span between 2013 and 2017. As Venezuela’s government revenue decreased dramatically, the government slowly realized the gravity of their problem of heavy dependence on one resource. In the past, Venezuela’s wealth and focus on oil exports led them to import more of their food and consumer goods. In 2013, food accounted for 18.41 percent of all of its imports.

President Chavez’s previous overspending on welfare created large fiscal deficits and the economy kept shrinking due to cheap global oil prices. President Maduro decided to simply print more money to sustain the welfare programs and import more food and consumer goods, but that is an extremely short term solution to their problem. Venezuela was trapped: the more bolivars (VEF) it printed to fund imports, the more the currency depreciated. The increase in imports for everyday goods, in combination to years of added regulations from the Venezuelan government (such as price control) and inefficient operations of nationalized businesses, caused domestic production of food and goods to shrink. With greater reliance on the government for the distribution of goods and services, only a few US dollars to spend on imports, and a decrease in welfare funding, there was a sudden scarcity of products within Venezuela. As the bolivar (VEF) became worthless, no one wanted to buy Venezuela’s debt or lend them money. President Maduro tried again to mitigate the bolivar’s decreasing value through various policy attempts that proved to be equally as disastrous; he raised the minimum wage by more than 3,000% and later hacked off 5 zeroes on the bolivar currency. But Venezuela fell short of achieving long term economic stability and these actions only elicited a deeper inflation crisis. Finally, the short term effects of Chavez’s policy to exchange welfare programs for popularity had worn off and the negative long term consequences began to emerge under Maduro.

Under Maduro, the normally subsidized medicine and food were not available to the poor because the government ran out of money and supplies. During this time, around 84 percent of the population identified as poor. To make matters worse, in the midst of this crisis, political corruption permeated the economy. Nicolás Maduro tweaked the political system to ensure that he could take advantage of the nation’s resources by using a complex currency system. While the bolivar became worthless and the demand for a more stable currency such as the US dollar arose, Maduro set the official government exchange rate at 10 bolivars per $1. However, only allies and elite friends of President Maduro could access this special rate, who then imported food and goods and sold them on the black market for a massive profit, to ultimately ensure that Maduro could maintain his power through near total control of goods and the cooperations of his allies. Most Venezuelans had no choice but to turn to the black market to access US dollars with exchange rates in the tens of thousands of bolivars.

Running out of options, Maduro turned to issuing local currency debt to raise money for Venezuela. However, the Trump administration responded by restricting Venezuela from selling their government debt in the US, making it more difficult to access foreign currencies and get out of their inflation. But most ambitious of all, Maduro is currently betting on a new type of currency to solve the economic crisis: the Venezuelan petro. It is an attempt at a virtual currency or cryptocurrency backed by commodities such as oil, gas, gold, and diamonds and intended to supplement the Venezuelan bolivar fuerte (VEF) while aiding in the mission of overcoming US sanctions. On the first pre-sale day, the petro raised $735 million and current prices are $62 for a barrel of oil. The Venezuelan government argues that this revenue could help pay part of the country’s obligations and is hopeful to one day use the petro as a daily currency.

Financial experts from the Washington Post find this ambitious plan incredibly risky. Though they are linked to oil reserves, the initiative can only be a superficial solution as long as the central bank continues to print money to cover government spending, which is what caused the inflation in the first place. More importantly, there is a lack of credibility. Implementing the petro is not the best policy because it circles back to the idea of trust—if no one believes in the cryptocurrency, no one is likely to use it. According to the Washington Post, “few Venezuelans appear to have faith in the fix (the petro), with many expressing broad fears that it may only make the situation worse.”

Often, economics are a self fulfilling prophecy and an economy’s state is rooted in social perceptions and belief. In fact, there is speculation of whether the petro is backed at all, as there is no evidence of active oil drilling or indication which reserves are used to back the currency. At the same time, because social perception influences economic actions, Venezuela is looking to legitimize the petro through active participation in using the petro as currency. An example is Venezuela’s expressed desire to pay for imports from Brazil with the petro. Another way Venezuela is implicitly forcing their citizens to partake in the petro initiative is in processing fees of one of the most important government issued items: the passport. The financial crisis has Venezuelans dwelling in social unrest. In fact, an estimated 2.3 million people have been fleeing the country since Nicolás Maduro’s ascendance to presidency in 2014 and is said to be the biggest migration of people in Latin America’s recent history. With large flocks of people emigrating, Ecuador and others are tightening immigration laws and requiring passports (reported to take up to two years to approve) to restrict access. Venezuela’s mandate that passport fees are to be paid in petro may be an economic policy move, but it is also a political decision from President Maduro. The past policy attempts to fix Venezuela’s economy from both Chavez and Maduro have been vast but short-sighted, yet one thing continues to ring true: in the root of Venezuela’s economic crisis lays political turmoil.

from Brazil with the petro. Another way Venezuela is implicitly forcing their citizens to partake in the petro initiative is in processing fees of one of the most important government issued items: the passport. The financial crisis has Venezuelans dwelling in social unrest. In fact, an estimated 2.3 million people have been fleeing the country since Nicolás Maduro’s ascendance to presidency in 2014 and is said to be the biggest migration of people in Latin America’s recent history. With large flocks of people emigrating, Ecuador and others are tightening immigration laws and requiring passports (reported to take up to two years to approve) to restrict access. Venezuela’s mandate that passport fees are to be paid in petro may be an economic policy move, but it is also a political decision from President Maduro. The past policy attempts to fix Venezuela’s economy from both Chavez and Maduro have been vast but short-sighted, yet one thing continues to ring true: in the root of Venezuela’s economic crisis lays political turmoil.

SOURCES:

https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2018/08/25/a-rude-reception-awaits-many-venezuelans-fleeing-their-country

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-economy/venezuelas-annual-inflation-hits-488865-percent-in-september-congress-idUSKCN1MI1Y6

http://go.galegroup.com.libproxy1.usc.edu/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA524864014&v=2.1&u=usocal_main&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/maduro-has-a-plan-to-fix-venezuelas-inflation—-which-may-make-things-worse/2018/08/19/7a6ee048-a3bf-11e8-ad6f-080770dcddc2_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.87c509cca661

https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/398286313?accountid=14749&rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

https://www.forbes.com/sites/garthfriesen/2018/08/07/the-path-to-hyperinflation-what-happened-to-venezuela/#4c9a7a3215e4

https://cointelegraph.com/news/venezuela-mandates-passport-fees-must-be-paid-in-controversial-cryptocurrency-petro

https://www.scmp.com/tech/blockchain/article/2167274/want-passport-venezuela-tells-citizens-pay-travel-document-state

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/02/venezuela-petro-cryptocurrency-180219065112440.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/20/venezuela-bolivars-hyperinflation-banknotes

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/VEN?year=2017

https://tradingeconomics.com/venezuela/consumer-price-index-cpi

https://www.cato.org/research/troubled-currencies?tab=venezuela

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2017/04/06/how-chavez-and-maduro-have-impoverished-venezuela

https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2017/10/03/2194217/how-did-venezuela-get-to-this-point/https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=19451https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/07/16/world/americas/venezuela-shortages.html

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.