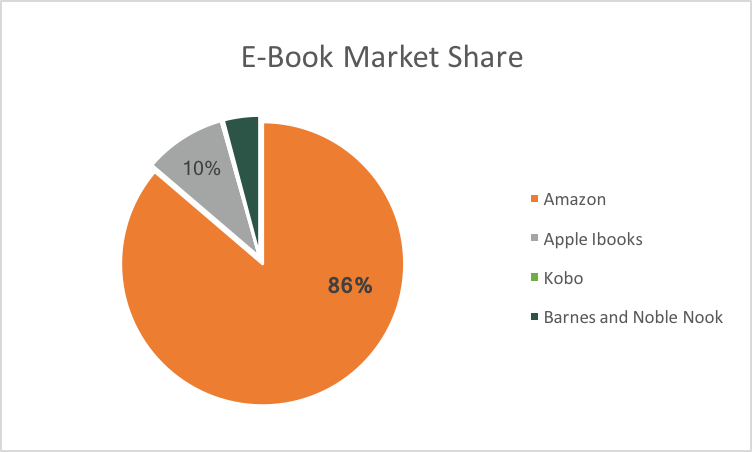

Google and Amazon don’t look like traditional monopolies, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have monopoly power. Google dominates 80% of the online search market and Amazon 87% market share of the e-book market.

It is harder to recognize these tech giants as monopolies because they do not have a tangible product. Whereas, it is easier to notice how our choice of airline or cable company is limited.

A Brief History of Antitrust in the United States

The United States Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 in an effort to prevent companies from having monopolies that stifle competition, harm consumers or raise prices. The Sherman Act, along with the subsequent Federal Trade Commission Act and the Clayton Act, is the core of American antitrust law.

These antitrust regulations were enforced aggressively by the Justice Department from the 1930s until the 1960s. Then came Robert Bork, the Yale Law professor and failed Supreme Court nominee. Bork argued that the only concern of regulators should be if prices for consumers were dropping. His ideas became the policy of the US Department of Justice when he became solicitor general under Richard Nixon and have remained the mindset of the government until today. Bork’s ideas on antitrust are at the center of modern American antitrust regulation enforcement.

In Move Fast and Break Things Jonathan Taplin argues that Amazon, Google, and Facebook would all be prosecuted under antitrust laws if it wasn’t for Bork.

Are Google and Amazon Monopolies?

In the post-civil war era, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil had a monopoly over the oil industry. Standard Oil controlled every stage of oil production and distribution. They did everything from own the refineries and pipes to building their own oil barrels and hiring scientists to discover new uses for oil products. Standard Oil’s monopoly ended when, in 1911, the relatively new Sherman Antitrust Act was used to break up Rockefeller’s monopoly into 30 individual companies.

Unlike the monopolies of the robber baron era, Google and Amazon lack a tangible product. They don’t have physical control over all production of steel or ownership of all phone lines. With Google or Amazon, there isn’t anyone or anything standing in the way of someone creating a new search engine or e-book market. However, their domination of their respective markets limits the ability for a new competitor to be successful.

The Supreme Court has defined monopoly power as “the power to control prices or exclude competition.” This definition also includes an assumption that the company has a majority market share. Using this legal definition as a guide, let’s see if Amazon and Google have monopoly power.

86% of all e-book sales in the United States occurred on Amazon in 2016, according to Authors Earnings’ February 2017 report. Amazon’s monopoly market power gives them the ability to control prices or even stop all books from a publisher from being sold on Amazon. Amazon’s ability to control prices makes them not only a monopoly but also a monopsony.

An example of Amazon’s monopsony power was evident in Amazon and Hachette Books’ 2014 pricing dispute. During their pricing dispute, Amazon stopped all presales of Hachette books and caused shipping delays. In this case, Amazon was exhibiting more monopsony qualities, when one buyer controls a market because through their control of the distribution of books they are the largest buyer of books. Since Amazon is the largest seller of books Hachette was forced to bend to Amazon’s will. Hachette was ultimately able to win a little and in the resulting deal with Amazon was able to gain more control over how their e-books are priced on Amazon. As a whole because Amazon occupies such a dominant share of the e-book market its sheer dominance allows it to set prices.

Google, like Amazon with their sector, has monopoly market share in search. According to Stats Counter, in September 2017 Google had an 85% market share of internet search in the United States.

Further proof of the market consolidation of the search market is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) score, which measures the concentration in a particular market. Antitrust agencies consider a market with a score of 2,500 to be highly concentrated. For example, after the American Airlines and US Airways merger, Reagan National Airport had an HHI score of 4,959. The search market has a score of 7,402.

Google’s monopolistic power goes beyond just its monopoly market power over search does. Google not only controls search, but they are also own the most popular created the modern version of horizontal integration.

Google, along with Facebook, dominates the online ad market. Google and Facebook essentially have a duopoly of all online advertisings with more the 60% of all internet ad revenue, according to an analysis by Reuters of their quarterly reports. Google controls everything from the service that hosts ads on websites to the service that buys ads to put on the website to the website user analytics to the web browser people use to access a website. John Marshall, the publisher and editor of Talking Points Memo (TPM), describes being a publisher that relies on Google’s suite of products as like being “a serf on Google’s Farm.” If Google changes how they distribute ads they can completely ruin someone’s livelihood. For example, earlier this year there was the YouTube “apocalypse.” Google changed its policies and algorithm for determining if a video on YouTube should not have ads. The result was some video creators losing 80% of their daily income.

Are These Monopolies Good?

For consumers, Amazon’s monopsony of the e-book market looks appears to be good because they get lower prices. Amazon has not done anything to harm customers. Their low prices are one reason why regulators have not come after Amazon.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman argues that one of the reasons why Amazon is able to control the market is its ability to kill buzz. Book sales rely on buzz from word of mouth. However, if Amazon does not carry a book you are less likely to buy a book and then the book will not be as widely read, have less buzz and not sell as many copies. Krugman asserts that “By putting the squeeze on publishers, Amazon is ultimately hurting authors and readers. But there’s also the question of undue influence.”

Monopoly power can also lead to a stagnation in innovation. If a company does not have another company with the potential to compete with them there is no motivation to innovate. If you have such a large market share there is no incentive or need to innovate to get new users or to maintain your existing user base or its revenues.

Even if Bing had a substantially better product it would still struggle to make a dent in Google’s user base. It wouldn’t necessarily lead to Google to innovate as well because Google’s market power and horizontal integration make the switching costs high. These high switching costs reduce your likelihood of using a new search engine. Furthermore, even though the barrier of entry for creating a new search engine or website is low, but Google’s horizontal integration makes it difficult for any new company to break through.

An example of competition and the potential for innovation is Facebook and Snapchat. In 2013, Facebook tried to buy Snapchat for $3 billion, but Snapchat turned them down. Snapchat and its growing user base remained a Facebook competitor. This competition should indeed push both platforms to innovate. However, instead, Facebook chose to essentially copy Snapchat’s features. Instagram introducing stories was an attempt to copy Snapchat stories. Facebook only tweeted Instagram stories a little to differentiate themselves from Snapchat, Facebook. Even though Instagram stories were not an innovation, they are still an example of completion producing new features for consumers. Facebook’s cloning of stories appears to be on track to both maintain and grow its user base. Currently, according to Jumpshot, Snapchat currently has the largest share of new users, but their share is shrinking and Instagram’s is growing.

How to Deal with These Monopolies

Those who align with Robert Bork would argue that there is no need to break up Amazon or Google because the prices for consumers are not being raised. In the case of Google, there was never even a price paid by the consumer.

But as we explored there are downsides to these monopolies, so what should we do about them? Are our antitrust laws from over a century ago built to regulate companies with products the bills’ author could have never imagined?

Jonathan Taplin has purposed a series of possible ways to break up or regulate digital monopolies like Amazon and Google. In a New York Times opinion piece, he laid out three possible regulatory options: option one is to block the major digital players from acquiring each other. Another possibility is to treat them like public utilities—which would require them to license out their patents. Or a third option would be to remove the “safe harbor” clause from the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which according to Taplin allows companies “to free ride on the content produced by others.”

Actually, breaking portions of these new monopolies would require the Justice Department to return to its pre-Bork hardline position on antitrust. So maybe the best way to deal with these tech monopolies is to institute some creative regulations to curtail some of the more negative effects of their monopoly power.

Sources:

http://www.history.com/topics/john-d-rockefeller

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/opinion/paul-krugman-amazons-monopsony-is-not-ok.html?_r=0

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/14/technology/amazon-hachette-ebook-dispute.html

http://fortune.com/2017/07/28/google-facebook-digital-advertising/

https://www.recode.net/2017/9/19/16308788/snapchat-instagram-sign-ups-new-users-us-global