Ricardo Ceja scowled as he flipped through recent paystubs for his job trucking cargo to and from the Port of Los Angeles. His October salary is $1,680, but his employer cut more than a third for costs like truck repairs, and won’t reimburse him for several hundred dollars spent on fuel.

The total amounts to much less than what Ceja expected to earn when he took on the job several years ago, and he sympathizes with many fellow truckers who have fled the industry seeking better wages.

“They pay me every week, but they deduct whatever they want,” he said on a recent afternoon at his Lawndale apartment. “They throw you a bone with a string.”

The shortage of truckers has exacerbated congestion at the ports, putting pressure on the entire shipping trade. Over the past several months, cargo at the Port of L.A. has been delayed a week or more, angering retailers made to wait for their products in the pre-holiday crunch. In some extreme cases, the lag-time has stretched for 30 days. As a result, shipping companies aiming for speedier arrivals could choose to divert their loads, reducing trade in L.A.

“We run the risk of losing business to other ports,” said Port of L.A. spokesman Philip Sanfield.

Truckers aren’t solely to blame for the delays, but they are essential cogs in a global system that demands an efficient infrastructure — and they have few incentives to stay in the business. Because most truckers are paid per load, not per hour, their earnings are especially pinched in times of congestion.

“They are the ones who suffer, not the shipping companies and not the trucking companies,” said professor David Bensman of the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations. As a result, “there’s almost a permanent labor shortage.”

For shipping companies, that shortage could lead to “a crisis in our business,” said one executive who asked to not publish his name.

“If we don’t have the adequate infrastructure with truckers, we’re going to be in a situation where we have goods coming in and out without people to move them,” he said.

While congestion is plaguing ports around the country, the problem is especially pronounced at the twin ports of L.A. and Long Beach, which together usher in about 40 percent of the country’s imports. The Port of L.A. alone pumps $260 billion into the national economy each year.

Now, those billions are passing hands more slowly than they used to. Companies including Lululemon, Ann Taylor and Lane Bryant, all women’s apparel brands, reported last week that their garments were stuck at port, according to Reuters. And, earlier this month, the Oakland-based Golden State Warriors basketball team complained that it had waited weeks for bobblehead figures to arrive.

Visit the port, and the impact is visible. In recent months, a dozen ships at a time have been stalled in the harbor for a period of about two days, when they should be entering swiftly, said Sanfield. Capacity on the docks has reached 95 percent, when it should be 80. Dwell time – the period a container waits on the docks — can be several days, when it should be just one. According to one shipping company CEO, some containers have waited up to twelve days.

Trucks line up at the Port of Long Beach, in Long Beach, California October 15, 2014. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

All this means extra time for truckers to get their loads, and extra time that they must loiter at the terminal without earning money.

Multiple reasons account for the delays, according to shipping company and port representatives. Increased cargo loads have caused some of the biggest snags. Several years ago, L.A. received ships with a maximum of 10,000 containers measured in “twenty-foot equivalent units,” or TEUs, said Sanfield. A ship carrying 6,000 TEUS was considered the standard “workhorse.” Now, ships with up to 13,000 TEUs are steering into the harbor, accounting for the 11 percent increase in imports from the previous year.

All that cargo has to get unloaded – but there aren’t enough chassis to go around. Shipping companies that once supplied their own chassis have cut back, finding the maintenance too expensive. Meanwhile, unloading containers has gotten complicated with so many shipping lines forming alliances and carrying separate orders on the same trip. Instead of all the cargo going to one place, it often needs to be sent in multiple directions.

Dockworkers have dragged the pace further. Since July, nearly 20,000 longshoremen have manned their towering cranes and levers without a contract. When negotiations similarly stalled in 2002 and employers accused the workers of go-slow tactics, ports along the West Coast shut down for 10 days – a catastrophe that some business groups estimate cost the economy $1 billion per day.

These factors form a cycle that feeds on itself, said Patrick Burgoyne, CEO for shipping company NYK Group, at a recent talk at the University of Southern California’s business school.

“There’s no greater means to suck up capacity on a facility than to have imports sit for twice or three times as long the time they’d usually sit,” Burgoyne told the audience of several dozen industry suits and a handful of business students. “When you lose a day, you might as well add a week on the back end to clean up.”

Truckers are part of the equation, he added.

“For the 20 years I’ve been around… the drivers in the ports have had it tough,” said Burgoyne.

SAN PEDRO, CA – OCTOBER 20, 2014: Trucks line up at the Port of Los Angeles on OCTOBER 20, 2014. ( Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times )

Truck capacity has dropped 16 percent since 2008, according to the Drayage Truck Registry, underscoring the volume of people leaving the industry. While 16,000 trucks once serviced the ports, only 13,500 are now registered.

Low wages are at the root of the labor shortage. The majority of truckers are paid by the load, not the hour, because they are considered independent contractors rather than employees. Their paycheck depends on the number of trips they can make a day to places like the Inland Empire, Ontario and San Diego. In congested times, that’s very few.

Ceja, the trucker, says the cargo pick up process takes about five hours, and sometimes up to nine. Ideally, drivers should need just one or two hours to drive into the pick-up terminal, check with security, hoist containers onto their vehicles and zoom away.

Ceja only gets paid to wait if the delay is longer than two hours – and that’s not including time for the port lunch break (an hour and a half) and other work breaks (each half an hour).

“This is modern age slavery, and they’ve been getting away with it,” said Ceja, who came to Los Angeles from Guadalajara, Mexico, as a teenager. After working as a bus driver, he became a trucker hauling cargo across the country so he could visit his son and daughter living in Wisconsin. But that job became too taxing, and now Ceja’s work revolves around the port.

Several days a week, he enters a maze of sections marked by a puzzling mix of numbers and letters. Systems are haphazard and frequently change. The first time Ceja first attempted to get a load, he spent three days in confusion before giving up.

Ceja’s employer, LACA Express, pays drivers $45 to deliver a full container and $20 for an empty one. Sometimes LACA offers bonuses, like $20 for a refrigerated container, which is heavier than an average container. The company gives an extra $5 for nighttime work. LACA also pays 22 percent of Ceja’s fuel costs.

But at the same time, LACA charges Ceja a monthly rate for using the truck. The fee is considered a payment to help Ceja buy the truck in installments, and eventually go into business for himself. Paying $250 a month, he expects that process to take five or six years. Meanwhile, he’s paying deductions as if he already owns the truck — for insurance, registration, inspection, parking, repairs and fuel. It eats hundreds of dollars out of his paycheck.

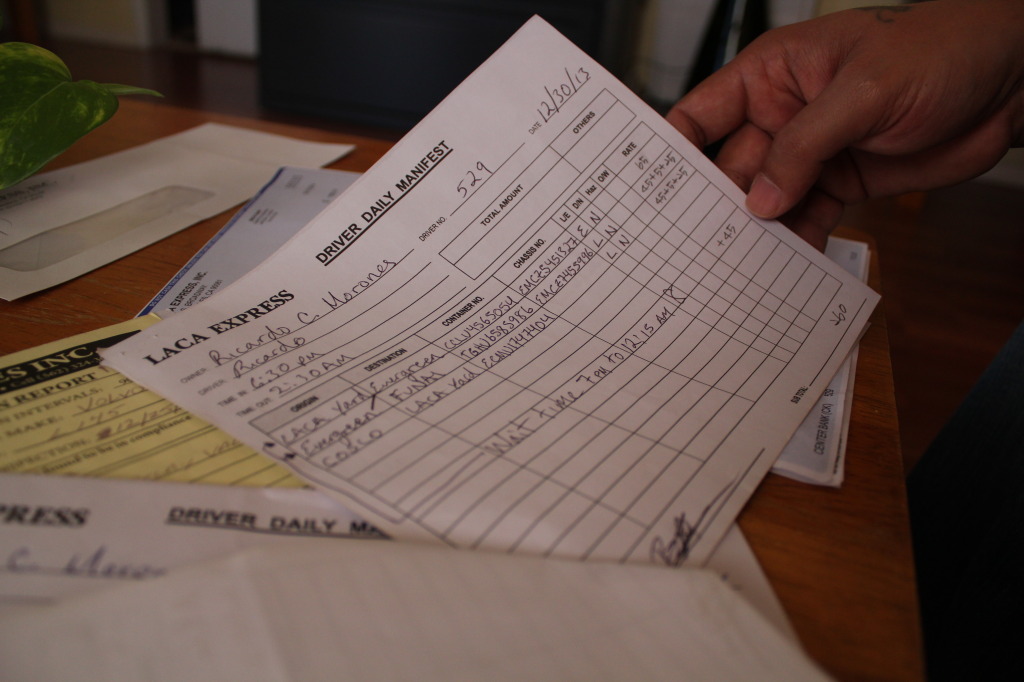

A closer look at Ricardo Ceja’s paystubs shows just how much he’s losing — not making. | Daina Beth Solomon

Annually, Ceja says that his pay comes to roughly $30,000 after deductions, a figure that matches statistics from the California State University Long Beach. A researcher found in 2007 that the median annual salary for a port trucker comes out to about $37,000. That equals a pay rate of $12.37 an hour for 60 hours a week. As independent workers, these truckers do not earn paid vacation, social security, workers compensation insurance or health insurance.

Truckers in other L.A. industries, in contrast, earn about double that amount, according to a study by trade economist John Husing.

His consulting firm Economics & Politics, Inc. calculated that, to entice those better-paid drivers into port jobs, their salary would need to increase to roughly $21.27 per hour at 40 hours a week, and include benefits. The full package would be $44,246 in salary and benefits, placing drivers into a middle class income.

LACA frames Ceja’s position as an opportunity for drivers to buy their own trucks on the way to launching their own businesses. The CEO and president did not return calls requesting comment.

Yet many truck drivers can’t hang on to the job long enough to buy their trucks, Ceja claims. They have an accident or get sick with an illness they can’t afford to treat without insurance, and give up. Drivers are especially susceptible to cancer-causing pollutants from the diesel-reliant machines at the ports, as well as their own diesel-run trucks. A recent study by the South Coast Air Quality Management District detected the highest cancer risk in Southern California clustered in and around the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, with the potential to affect about 1,050 people in 1 million. Diesel exhaust contributes to more than two-thirds of the air pollution.

Giant cranes at the Port of Los Angeles help transfer containers from ship to truck. | Daina Beth Solomon

“They work you, work you, work you — as one way to get rid of you,” said Ceja. “Because you don’t have any benefits, they know sooner or later you’re all going to be sick.”

In October, Ceja joined a couple of hundred other drivers to go on strike, arguing that their status as independent owner-operators is a misclassification. They want to be deemed employees so that they have the right to unionize and get health benefits. Eight trucking companies came to the negotiating tables in late November, and discussions are ongoing.

The solution won’t be as simple as raising wages. Trucking companies keep their wages low because they are forced to keep prices low. When the Motor Carrier Act deregulated the industry in 1980, barriers to entry weakened, and entrepreneurs began their own trucking businesses. As the competition boomed, truck companies lost their pricing power. They now have to keep wages low in order to turn a profit.

To Bensman, the Rutgers professor, it appears that the trucking companies are subsidizing international consumerism just to stay in business.

“The truck drivers are subsidizing the global economy because they’re accepting bad congestions and bad health,” he said.

Drivers go on strike at the ports in November. | Justice for LA/LB Port Drivers Facebook

Bensman, who visited L.A. recently to talk with strikers, thinks trucking companies must find a way to enhance their pricing power. One option could be to ditch the “owner-operator” system and turn contractors into employees, thus reducing competition.

For now, he doubts that the current negotiations will yield far-reaching outcomes. Only eight companies have joined the talks, while more than a thousand do business at the port.

Ceja says he refuses to accept the conditions that lead to his meager paycheck. When he has to wait to pick up loads in the maze of terminals surrounding the docks, he tries to convince other truckers to join his fight for better pay and benefits.

“Look man, this is what’s going on,” he tells them. “We’re not free to do business. You really like the way this is happening?” Sometimes the drivers tell him to leave the industry if he thinks it’s so bad, but Ceja has resolved to stay until he can earn the money he says he deserves.

“That’s the American dream, right?” he asks rhetorically. “Having your own business, being able to afford a home, and have a good life and a nice retirement.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.