Despite a growth of legal channels for watching shows online, the volume of pirated content, pirated movies, TV shows, music, books and video games is growing rapidly. Pirated content viewers are largely condemned for stealing, as its assumed that they engage in copyright infringement. From a moral standpoint, it’s easy to argue that producing or viewing pirated content is disrespectful to the authors or brands that create it. But financially, do brands really make less money because of pirated content consumption? Morality aside, maybe that’s another story.

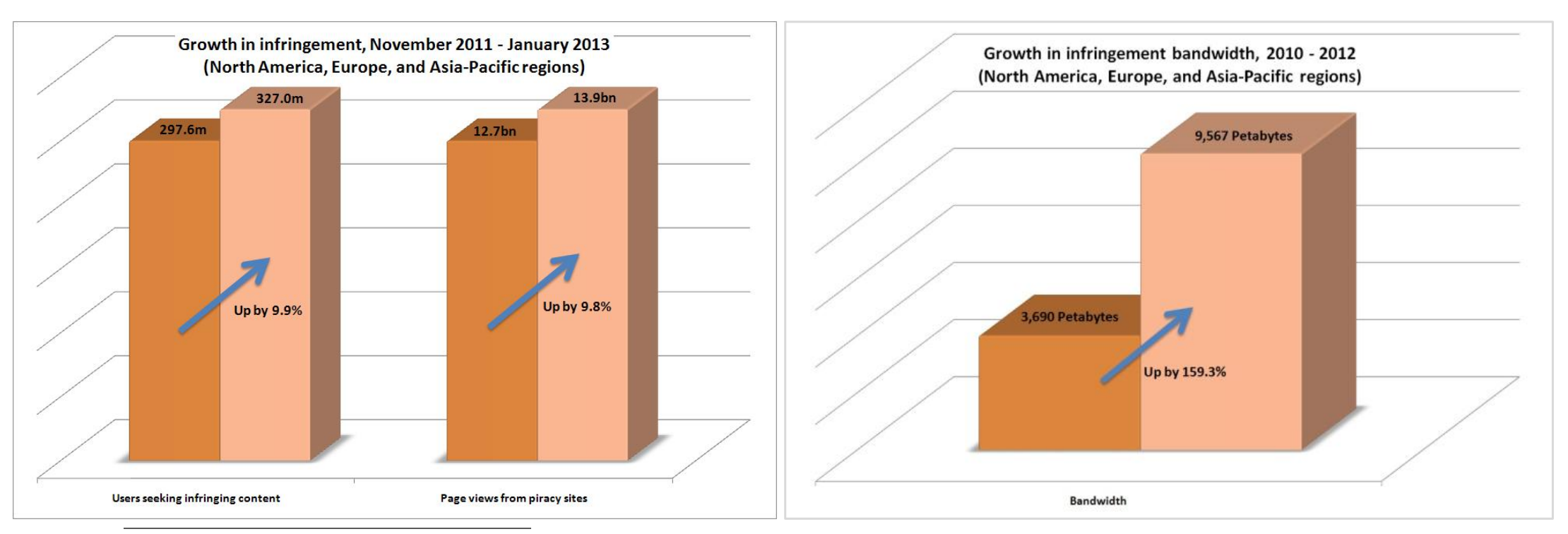

According to a study called “Sizing the Piracy Universe” from NetNames, both the number of internet users who regularly pirate content and the amount of bandwidth consumed from pirated content increased significantly between 2010 and 2013, and the internet-based infringement continues to grow at a rapid pace.

In history, companies and governments have never stopped trying to uproot piracy.

Many pirated content consumers use cyberlocker, a third-party file sharing service, to download and upload movies and music. In January 2012, the Hong Kong-based MegaUpload was closed and sites associated with Megaupload were shut down by the United State Department of Justice for copyright infringement. From 2011 to 2013, thanks to international law enforcement efforts, the number of cyberlocker use dropped 8%. Worldwide, even countries like China, which is notorious for culture copyright violations, also issued regulations trying to uproot pirated and unauthorized content and shut down several major peer-to-peer file distribution hubs, including VeryCD and BtChina.

However, in the US, bills like SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) and PIPA (Protect IP Act) died in Congress in 2012 after massive opposition (actually led by Google, with help from Wikipedia) in the name of protecting internet freedom.

There’s been several major pirate channels to open up to fill the demand.

For sites like YouTube, a hotbed for users to generate mash-ups (mix of copyright content by fair use) also have a blurred line in copyright infringement. And that’s another story in terms of whether the content is pirated or fair use. In addition, BitTorrent websites with its peer-to-peer distribution system still exist, survive and even thrive with never-decreased need for free content.

The Pirate Bay is a more infamous one. Established in 2001 by a Swedish anti-copyright organization and start web service in 2003, today’s Pirate Bay website provides access to all around the world.

The Pirate Bay was outlawed multiple times, once move the server to Netherland, and has been involved in as well as bring users many lawsuit cases in its history. For example, in 2009, Stockholm district court sentenced four founders of The Pirate Bay to one year in prison each and handed out a total of $3.6 million in fines. In 2006 the US government pressured the Swedish government and threatened to blacklist the Swedes within the World Trade Organization if Sweden did not deal with the website.

Legitimate services, including Netflix and Amazon.com, are affected by pirated content views. The financial loss results from customers turning to pirate websites for free content. Recently, a 27-year-old New York man was accused of uploading Ultimate Fighting Championship content to The Pirate Bay and Kickass Torrents which were worth more than $32.2 million. The man, Steven Messina, had uploaded 141 UFC presentations to those file-sharing sites under the name of “Secludedly,” and provided a PayPal donation link to keep his business.

The world seems to be showing little tolerance towards piracy. However, are brands like Netflix, Amazon, and even the UFC losing as much money from piracy as they claim?

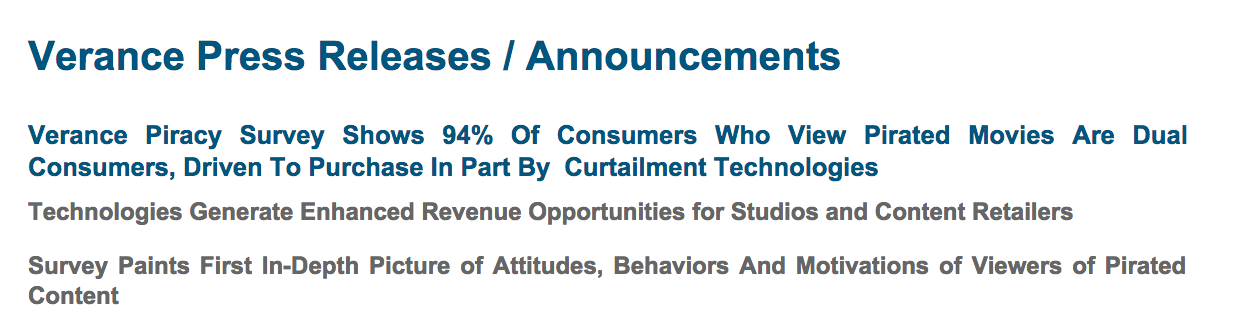

Despite assumptions about how “bad” piracy can be, some argue that piracy loss can actually convert to revenue opportunities. According to a recent study conducted by Verance Corporation, an estimated 94% of American consumers viewing pirated movies are also buying legitimate copies of content. Namely, most of consumers in the US viewing pirated movies are actually “dual consumers.”

The survey identifies six distinct categories of consumers of pirated movies: “Occasionals” or “dual consumers” who prefer to watch legitimate copies but will view pirated content if possible, and “Convenience Streamers” who are mostly avid movie viewers with a preference for viewing via streaming. When subscription services fail and pirate channels are available, they will turn to the more convenient option.

There’s more. There’s the “No Big Deals” who see no harm to watch pirated content, but still willing to spend money for theater experience; “Content Enthusiasts” who tend to allocate a portion of their budgets to legitimate movies; “Cost Sensitives” who buy legitimate copies based on moral considerations; and “Library Builders” who collects both legitimate and pirated copies in order to build a collect that can be viewed through multiple devices.

In all categories, there are no individuals who strictly depend on pirated content and never pay for it. The study found that people “steal” not because they cannot afford legitimate copies, but because pirated content is convenient.

Although it can be considered immoral to view pirated content, from the perspective of copyright holders, including major and independent studios, content providers and content retailers, sometimes piracy loss actually can be converted to revenue opportunities.

Even if pirated content is illegal and immoral, it does not mean it translates into brands losing money. In a circuitous way, they might even get revenue opportunities out of this behavior. Then, is this one of the reasons brands turning a blind eye to pirated content consumption? Maybe yes, but don’t say it out loud.

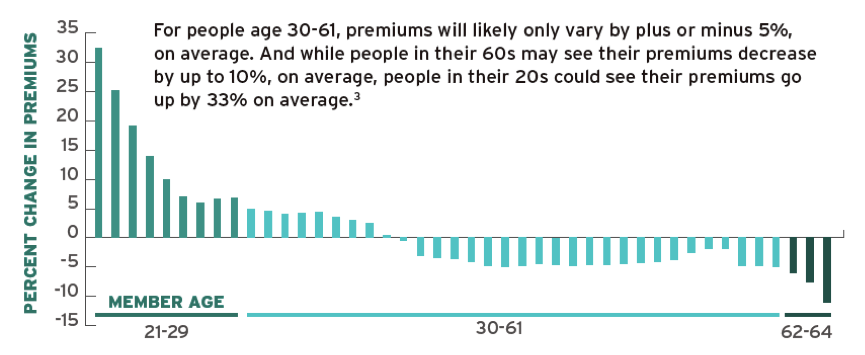

Some people may argue that there are subsidies available for young people with limited income. Yes, there are. But the truth is, for those who earn a little more than the poverty line, it’s hard for them to choose whether to earn more with no subsidy or to earn less with a small amount of subsidy. More importantly, for those healthy people who usually don’t have health problem, they would rather end up with paying penalties instead of purchasing health insurance, which is far more expansive than the penalty.

Some people may argue that there are subsidies available for young people with limited income. Yes, there are. But the truth is, for those who earn a little more than the poverty line, it’s hard for them to choose whether to earn more with no subsidy or to earn less with a small amount of subsidy. More importantly, for those healthy people who usually don’t have health problem, they would rather end up with paying penalties instead of purchasing health insurance, which is far more expansive than the penalty.