Los Angeles—The Fashion District is an anomaly in today’s modern retail marketplace. This is not because men standing on wooden boxes use megaphones to announce deals like, “Ten dollars, ten dollars, everything ten dollars…” to the tune of Mexican banda music blaring from an old boom box as shoppers struggle to make their way through Santee Alley’s dense crowds without stepping on merchandise splayed on the street. Rather what’s most surprising is that in today’s money culture of credit cards, mobile payments, online banking and Bitcoin, Fashion District retailers and shoppers alike prefer to conduct their business in cash.

Many young Americans perceive the “cash only” culture as a throwback to a bygone era. Paying with cash makes it more difficult to track personal spending—who likes keeping receipts?—and provides none of the cash-back or rewards benefits that many credit card companies offer. However, from an owner’s perspective, cash payments afford businesses more flexibility in making everyday decisions. Companies can opt not to report revenue from cash transactions, effectively lowering their tax bill. They also avoid paying credit card interchange fees, which average about 2.5% but can be as high as 4% per transaction for some cards. “A $100 cash sale is $100 in my pocket,” says Neda Amanat, a manager at System: Women’s Clothing in the Fashion District.

Dealing in cash also gives retailers greater elasticity in pricing goods. Merchants in the Fashion District regularly negotiate on prices for customers purchasing wholesale or bulk orders. They are often inclined to knock off the 10% sales tax for any customer paying in cash, regardless of quantity. Ultimately this will allow them to move more merchandise. In essence, using cash helps small businesses skirt some financial reporting rules.

The decision to use cash may also have cultural ties. The Fashion District houses a large Hispanic community whose cultural markers are abundant; signs are in Spanish, street vendors sell Mexican candies, and stores promote deals for Quinceañera dresses. Considering Mexico’s sales tax rate is 16% and its financial system is perhaps less trustworthy than America’s, it’s no surprise that the Fashion District’s immigrant population prefers cash. In contrast, a 2013MasterCard survey found that the US is at the “tipping point” of becoming a cashless economy.

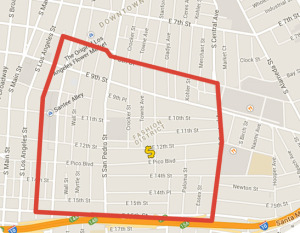

The problem with a cash-based economy is that criminal organizations also rely on this model to hide the proceeds from their nefarious activities. Last month more than 1,000 law enforcement officers raided dozens businesses in the Fashion District suspected of helping Mexican drug cartels exchange dollars for pesos through a trade-based money-laundering scheme. Officers arrested nine people and confiscated $90 million, the largest ever cash seizure by US law enforcement in a single day.

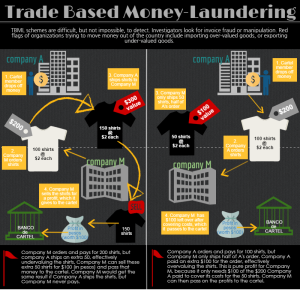

Drug cartels must constantly innovate ways to launder their illicit profits as law enforcement officials become savvier and nations enact increasingly cooperative financial regulations and reporting policies. During the September raid, deemed Operation Fashion Police, officials identified a complicated trade-based money-laundering (TBML) scheme the cartels employed to transfer drug profits back to Mexico. The Financial Action Task Force defines TBML as, “the process of disguising the proceeds of crime and moving value through the use of trade transactions in an attempt to legitimize their illicit origins.”

Drug cartels must constantly innovate ways to launder their illicit profits as law enforcement officials become savvier and nations enact increasingly cooperative financial regulations and reporting policies. During the September raid, deemed Operation Fashion Police, officials identified a complicated trade-based money-laundering (TBML) scheme the cartels employed to transfer drug profits back to Mexico. The Financial Action Task Force defines TBML as, “the process of disguising the proceeds of crime and moving value through the use of trade transactions in an attempt to legitimize their illicit origins.”

The key point is transporting value, which can include commodities in addition to currency. Drug cartels exhausted their options for directly moving cash. Depositing funds in an American or Mexican bank would raise suspicions, as would exchanging millions of dollars for pesos. Shipping or driving the cash home is incredibly risky. Instead the cartel will “deposit” relatively small increments of cash ($10,000-$150,000) with Company A, a complicit business in the Fashion District. Company A will do business with Company M, a Mexican company that is also a part of the drug cartel’s money-laundering network. Company M might order shirts worth the amount of money the cartel “deposited” with Company A, which then ships the shirts to Mexico. Company M sells the shirts in Mexico for pesos and incrementally deposits the proceeds in a bank account predetermined by the cartel. By converting their money into value, as shirts, the cartel can exchange dollars for pesos and transfer money from the US to Mexico without directly alerting banking officials. The process is not perfectly efficient at transferring money, but it is more effective than having the cash stuck in the US.

To prevent TBML, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) will require businesses in the Fashion District to report any cash transactions involving more than $3,000, as opposed to the $10,000 national reporting threshold. The Treasury Department issued this geographic targeting order (GTO) for six months, with the potential to renew it. This GTO is unprecedented in the scope and number of businesses affected.

“A geographic targeting order is a very blunt instrument,” Kent Smith, executive director of the Fashion District’s business improvement district, told the Wall Street Journal. “…It basically sends a message that every business in the area is involved in money laundering, and that is far from the case.” Law enforcement officials raided a few dozen businesses of the nearly 2,000 that the GTO encompasses. Retailers in the Fashion District worry that this increased regulatory scrutiny does not bode well for businesses.

Hector Vilchez helps run his family’s business Kukuly’s, most notable for its unique, hand-made jewelry. Kukuly’s also sells hand-made leather purses and belts for a fraction of the price shoppers would pay elsewhere. A braided brown leather belt with turquoise accents costs $40.00 at Kukuly’s, while the same item retails for $80 to $100, plus tax, at a similarly sized boutique on Melrose. Their $60-$80 leather purses would sell for upwards of $200 in Abbot Kinney. Vilchez says his customers prefer to pay in cash, and thinks the reduced reporting threshold will force his family to change certain aspects of their business to avoid the extra paperwork. Most of their customers spend well under the $3,000 threshold, but occasionally they fill large orders for purses or belts. They sell small clutches shaped like bows that are especially popular in large quantities, Vilchez says. “I don’t know if I’m going to sleep as well at night, you know,” he laughs, “because we run a good business, a clean business, but I don’t know maybe I will make a mistake.”

His fears are justified considering the amount of information and paperwork his business is now obligated to provide for transactions involving more than $3,000. To legally accept this much cash, Vilchez must see a valid government ID, record phone numbers, addresses, and names for everyone associated with the transaction, and obtain a written certification from a customer purchasing goods for someone else explaining the situation. This will require considerably more effort than accepting cash.

Joy Xie of Krustallos, her family’s jewelry and accessory store, shares similar concerns. Xie says her family will change many aspects of the business to comply with the new reporting restrictions. Krustallos sells the bulk of its merchandise to wholesale buyers. A prospective client will consider various items for about an hour, slect a few pieces and negotiate with Xie over quantity and price. After consulting her calculator Xie will offer a slight discount for a larger purchase, say 10 rings for $90 instead of 7 rings for $68, and suggest complementary items, like a matching necklace or a coordinating purse hook. The process continues until the customer pulls out a wad of bills, thumbs a few loose, and hands Xie the cash. She estimates her average customer spends $700-$1,000, but said it’s not uncommon for someone to spend $2,000 or $3,000 a few times a month. Those transactions, which previously were no different from every other, will now require Krustallos to collect that extra information from buyers. She worries customers will decide to spend less money if they have to spend more time filling out paperwork. Failing to properly document the transaction could subject Xie to up to $10,000 in fines, and that’s the minimum penalty. If the government finds a business willingly ignored the law the fines can double and individuals may also face prison sentences.

It’s too soon to say what effect the GTO will have on businesses like Kukuly’s and Krustallos, but a few ideas remain true today. Businesses in the Fashion District prefer to use cash, and so do their customers. It remains one of the few places in LA where shoppers can barter with retailers over prices, enjoy the “hunt” for a certain accessory or the perfect prom dress, and feel accomplished after acquiring every item on their lists for a fraction of the cost they might pay elsewhere. Shirae Christie lives in Costa Mesa and visits the Fashion District several times each year with her mom and her aunt. “I tell Shirae to carry exactly as much cash as she want to spend when [we] come [here], because if you bring more, you spend more,” says Christie’s mother. Regarding a potential shift of businesses from cash to credit cards Christie says, “I guess it would kind of take the fun out of the experience for me. Then [the Fashion District] would be like a dirtier version of Forever 21.”

Cash is the blood that courses through the veins of this wonderfully bizarre shopping locale in Downtown LA. The government-issued GTO will serve as a warning to cartels, but will not directly interfere with TBML or Mexican drug sales in the US. Perhaps a well tailored, government solution to such a serious issue was too much to ever hope for. For the next six months, with any luck no longer, retailers must try to remain hopeful that the GTO will not seriously constrict their cash flow and suffocate their businesses.