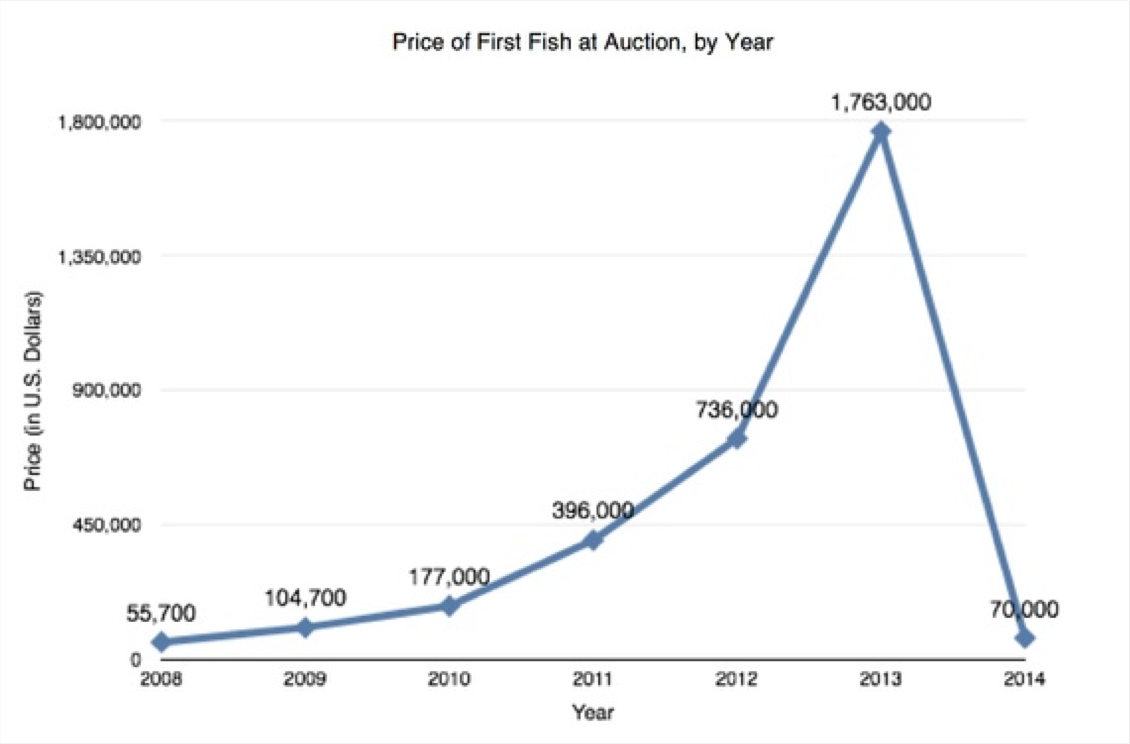

Kiyoshi Kimura, president of Kiyomura Co, paid $1.76 million for the bluefin tuna he had won at the Tsukiji Market auction in January last year. As his staff towed the prized tuna back to his restaurant, the cart carrying the giant fish was surrounded by groups of professional photographers. He posed for a photo before he cut the tuna, his employees clapping hands in the background.

The picture that ran next to headlines about the eye-popping price tag for a single bluefin tuna is a snapshot of a lucrative industry spinning out of control due to a decade of overfishing under lax regulation.

Fed by ravenous demand from sushi lovers, Japanese and European fleets have exploited the commercial value of bluefin tuna and nearly depleted its stock in the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean.

“The stock of bluefin tuna, by far the most valued tuna species, has been so heavily overfished in recent times that its collapse has become a very serious and threatening possibility,” said Fabio Hazin, chairman of The International Commission of the Conservation of the Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), at a meeting in 2008.

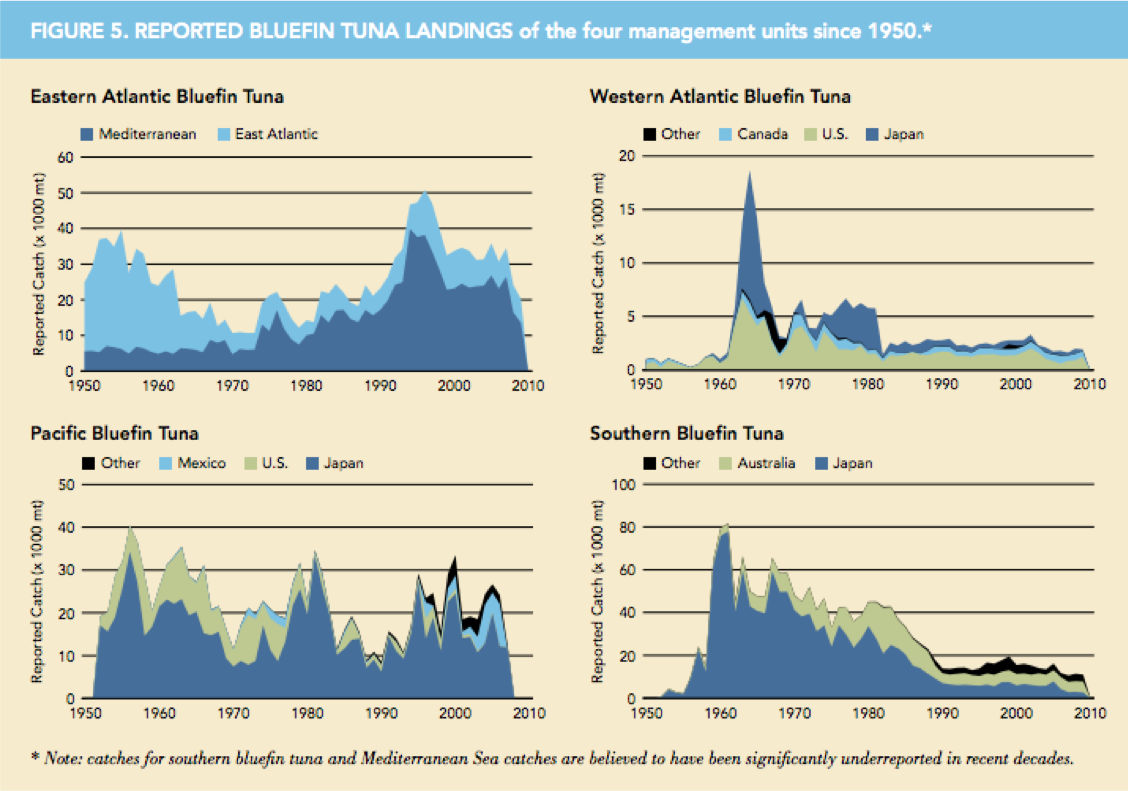

Days after Kimura bought his tuna, the Pew Charitable Trusts announced the number of Pacific bluefin tuna has declined by 96.4 percent from pre-1950 levels. The eastern Atlantic bluefin spawning stock has plummeted by nearly 75 percent over the past four decades, according to reports from ICCAT, a Madrid-based regulatory body with 47 members and the European Union.

Half of that loss, says ICCAT, occurred between 1997 and 2007, a period commonly known as “the golden years” among European fishermen. When the market for bluefin tuna took off in the 1980s, the advent of ranches — large coastal pens for fattening the fish before trading them with the Japanese — transformed the economic outlook of the industry. During the two decades followed, European ranchers and Japanese conglomerates worked together to take advantage of a lack of regulatory oversight. They caught as many as they wanted, and rested assured that state government would take whatever catch number they report for granted. The French government helped expand their fleets with subsidy, only to fuel a black market where trading unreported catch has become an international routine.

From Nobody to Somebody

Bluefin tuna has very few natural predators, but the species paid a price for becoming one of the most sought-after fish among well-heeled sushi devotees in Japan and worldwide.

In the 1960s, bluefin sold for a tiny fraction of its market price today. It was mostly ground up for cat food in the U.S., and dish made out of its meat held little appeal to the Japanese who preferred white-fleshed fish and shellfish. There were plenty of stock of bluefin around the northwestern corner of America, but commercial fishers considered it a trash commodity and passed it on to be the targets of weekend sportsmen.

The turning point came when sushi bars went global in the next ten years: Americans turned out to have an appetite for “toro,” the fatty underbelly of tuna commonly used for sushi. In Japan, people had grown accustomed to meat with strong flavors and dark flesh. It was also about this time that Japanese cargo planes, after delivering electronics to the U.S. market, started buying up cheap bluefin tuna near New England to sell them at a good price back home.

By the 1970s, bluefin tuna had caught on in Japan, prompting the nation’s importers to take in large quantities from fisheries worldwide. Fishing for bluefin in the western Atlantic increased by more than 2,000 percent between 1970 and 1990, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The average price paid to Atlantic fishermen for bluefin exported to Japan exploded by 10,000 percent.

Today, Japan consumes about 80 percent of the bluefin tuna caught globally. The country is home to the Tsukiji fish market, the world’s largest seafood wholesale center. There, the annual fish auction held on the first Saturday in January demonstrates how much hype there is around bluefin tuna. For patrons of the auction, winning the head of a single bluefin tuna at an outrageous price is a fight for status and free advertising. Kimura, who became widely known after he paid $1.7 million last year, also won the bid this year and in 2012.

The auction price, as shown above, has soared since 2008, before taking a nosedive early this year. “The wildly fluctuating price demonstrates only that the auction is subjective and distorted, dictated almost entirely by the bidders’ wealth and whims,” writes Emma Bryce, a reporter with The Guardian.

Ranching to the Utmost

During the golden age for catching bluefin tuna Japan’s demand turned several family businesses in France into fishing empires. But it was the advent of “ranching,” the industrial method of fattening bluefin in underwater pens before selling them on the market, that facilitated the ruthless catch, particularly in the Mediterranean Sea.

Originated in Australia, tuna ranches were introduced by Spanish and Croatian fishermen to the Mediterranean area around 1998, the same period when ICCAT instituted the first quota on bluefin tuna. The old-fashioned way was to catch the bluefin near the shore and kill them immediately before returning them to the port. The advanced method is much more complicated: Purse seiners transfer the catch to cages; Tugboats slowly carry the cages — for as long as a month — to circular underwater pens located in coastal waters; Fish in the ranches are then fattened for months on sardine, mackerel, and herring till their fat content, flavor and color match the demand of Japanese consumers. Tunas at harvest are shot in the head and kept cool in cold seawater slush; In the end, most of the fish are shipped deep-frozen to Japan on refrigerated vessels, while the rest are packaged and flown to Japanese markets, where they’d be auctioned off fresh. See a video on how ranching works below:

Those circular ranches revolutionized the industry. Fishermen were able to steer their vessels father from the port without worrying the fish caught would rot on their way back to the port. The deeper the water, the larger the bluefin, and the bigger the profit.

“What you gain is consistency in the quality and the supply, because you are not subject to seasonal factors,” says Rex Ito, president of Prime Time Seafood, a Los Angeles-based importer that provides 85 percent of the bluefin tuna needed in L.A. restaurants. “It’s an efficient way of producing a quality product.”

Earlier, the supply of fresh bluefin could only last for a few months per year, with just a tiny percentage of the catch being fat enough. The introduction of ranches means fishermen in his greatest capacity, and hold on to his stock till Japanese traders are ready to deal. For connoisseurs, a stable supply enables bluefin tuna to be on the menu year-around.

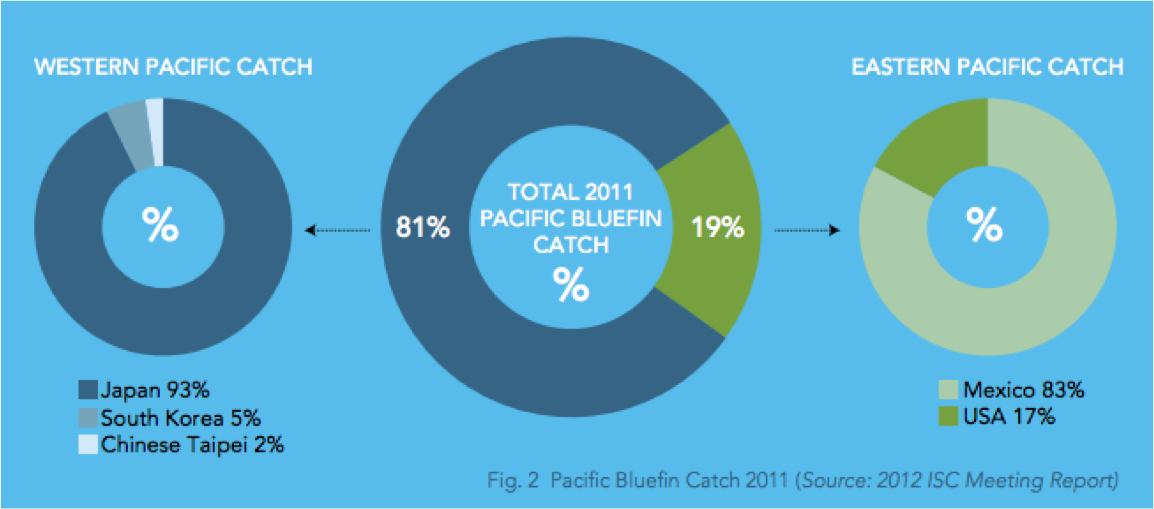

Tuna ranches, says Ito, is what gave rise to increased fishing capacity and over-catching. His biggest suppliers are located in Spain and Mexico, where bluefin tuna are ranched and sold to sushi bars in the U.S.

Compared to Spain’s long tradition in the bluefin business, Mexico is new in the game. The country, which now catches the majority of bluefin in the eastern Pacific Ocean, adopted the ranching technology around 2000.

“You wouldn’t necessarily save money by keeping the tuna in a cage and feed it. The process is actually fairly expensive. It’s quite an operation,” says Ito. “But farming or ranching is the future of a lot of seafood.”

In Europe, ranching has helped French fisheries strike a fortune between 1997 and 2007, depleting the stock of bluefin in eastern Atlantic Ocean by half, according to an investigative report from The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a global network of 185 investigative reporters.

In Sète, a small trip nestled along the Mediterranean Sea, bluefin fishing has been a regional vocation for generations of captains. But it was the rise of bluefin and the technique of ranching that made them one of the wealthiest fishermen communities in France. They now operate the world’s most productive tuna fishing fleet, of which 36 multimillion-euro vessels target bluefin tuna in the eastern Atalantic Ocean.

Government subsidies played a significant role in the renovation and expansion of Europe’s powerful fishing fleets. The European Union and its member states, encouraged by a strong market demand for bluefin tuna, has poured €26.5 million into vessels in Sète between 1993 and 2007. The average French purse seiner in 1998 was twice as long and four times as powerful as they were two decades ago. By 2008, there were 131 purse seiners in EU fleet, and another 500 ships owned by ICCAT members outside the EU. All of them served the cause of exploiting the bluefin community. For owners who took out bank loans to purchase their pricey vessels, the only way to repay the debt was to over catch.

Japanese companies, even though at the very end of the supply chain, chipped in with money. They are known as “the architects and financiers of the ranching industry,” because they partnered with Spanish and Croatian fisheries in building and running the facilities. Paco Fuentes, a business mogul from Spain, jointly ownes Drvenik Tuna, a Croatian ranch, with Japanese conglomerate Mitsubishi and local partner Conex Trade. The man also serves as the general manager of Fuentes & Sons, which has eight ranching subsidiaries in six countries. When interviewed on the dire state of bluefin tuna, Fuentes said he didn’t consider it “an endangered species.”

“There are a lot of small bluefin tunas in the Gulf of Lion waters [near France],” he told ICIJ reporters.

Fish Till You Drop, Authorities Say

Tuna ranches inspired fishermen to maximize the economic benefit of bluefin tuna, and brought sushi lovers a sufficient supply of toro meat. But when the feeding frenzy went unchecked, it became gateway to a decade-long, illegal fishing craze in the Mediterranean.

Seventy-five percent of the region’s bluefin tuna stock had disappeared between 1998 and 2007, says ICCAT. During the same decade, off-the-book trade in bluefin market is estimated to be $400 million per year, says ICIJ reports. One out of every three bluefin was illegally caught, and a majority of them were young fish that have not yet reproduced. In 2008, the amount of eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna traded on the global market was still 31 percent larger than ICCAT’s quota that year. In 2010, the gap peaked at 141 percent. Ranching made it difficult to track the number of bluefin caught mainly because much of its operation is done underwater. Raising undersized fish may hardly be noticed when ranchers cleverly place them in a good adult mix; Fleets could transfer the fish immediately to another vessel without declaring the catch; A diver can simply stops videotaping and allows the fish to pass unrecorded when transferring them from net to cage, thus falsifying the catch number.

Ranching made it difficult to track the number of bluefin caught mainly because much of its operation is done underwater. Raising undersized fish may hardly be noticed when ranchers cleverly place them in a good adult mix; Fleets could transfer the fish immediately to another vessel without declaring the catch; A diver can simply stops videotaping and allows the fish to pass unrecorded when transferring them from net to cage, thus falsifying the catch number.

Unreported and illegal catches were fueled by a lack of accountability. One French fisherman named Nicolas Giordano told ICIJ that he and his peers declared freely their catch number until 2006 to the laissez-faire French government. “The administration didn’t do its job, and at the time no one took it seriously,” he says.

Until 2007, the French officials never bothered to verify the numbers reported, neither did the Spanish and Italian governments. They adjusted the figure further downward to meet the quota and then sent it to the European Commission, which in turn reported to ICCAT.

“The only country to give their real figures would get fined, so in that kind of game, everyone lies,” ICCAT scientist Jean-Marc Fromentin told ICIJ reporters.

In 2008, ICCAT introduced Bluefin Tuna Catch Documents, a paper-based catch documentation system aimed at tracking down every step of the bluefin trade along the supply chain. But only a handful of countries, mostly big players, have updated their documents since 2014. In response, ICCAT has put forward an electronic catch documentation system to counter the rampant black market.

Forging Ahead

Fuentes & Sons, now a leading seafood supplier in Spain, announced in December its plans to become the first to raise Atlantic bluefin tuna on land. The company would invest €5 million in building a hatchery for the endangered fish, with the expectation of producing about 500 metric tons by 2015.

Japan’s Fisheries Agency, on the other hand, has decided to rein in the nation’s catch of immature Pacific bluefin tuna. Starting in 2015, it would reduce by half the quota of bluefin tuna that are three years old or younger compared to the average catch number during 2002 and 2004.

The biggest market for bluefin has seen its officials turn down several batches of dubious bluefin imports in the past few years, but a moratorium on fishing bluefin seems unlikely given its popularity and economic value.

“They wanted the fatty fish and they recruited the people who could carry out this work for them. Now that the system is out of control and markets are saturated, they are scrambling to distance themselves from it,” said Sergi Tudela, head of Fisheries at WWF Mediterranean.

Reference:

http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/01/sushinomics-how-bluefin-tuna-became-a-million-dollar-fish/282826/

http://www.icij.org/projects/looting-the-seas

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/world-on-a-plate/2014/jan/06/pacific-bluefin-tuna-auction-overfishing-sushi

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-09/tuna-species-sold-at-record-price-faces-overfishing-study-says.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/27/magazine/27Tuna-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2007/06/sushi200706

http://www.fis.com/fis/worldnews/worldnews.asp?monthyear=&day=11&id=67799&l=e&special=&ndb=1%20target=

http://bangordailynews.com/2014/03/23/business/japan-to-cut-bluefin-tuna-catch-by-half/

http://www.pewenvironment.org/uploadedFiles/PEG/Publications/Fact_Sheet/tuna-story-of-atlantic-bluefin-2013.pdf

http://www.pewenvironment.org/uploadedFiles/PEG/Publications/Fact_Sheet/tuna-story-of-pacific-bluefin.pdf

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.