Hollywood, California: long synonymous with film and television production; the Mecca of the entertainment industry. If you weren’t here, you weren’t anywhere. That said, movies and TV aren’t all about entertainment. To the hand that feeds them, they’re investments, and huge ones at that. Putting together a budget for the production of a film is a complex and intimidating process. That’s where state-based tax incentives come in, easing the financial burden and encouraging productions to stick around the area to generate future economic benefits. However, such incentives have spread to other states and countries, disrupting California’s film business at its core and bringing into question it’s worth.

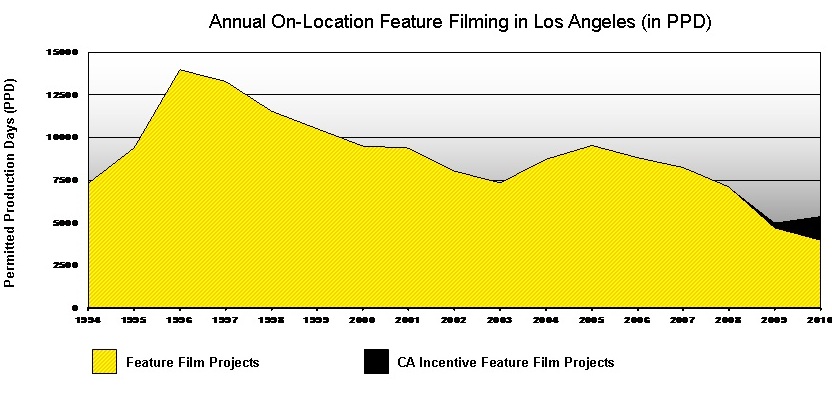

Dubbed runaway production, it has waged a war of attrition on Hollywood production over the last decade, and if not for the government incentivized projects (represented by black on the graph below, provided by runaway production outreach program FilmWorksLA), 2010 would have been a record low year for Los Angeles productions.

California’s legislation on film production credits was established as a defense system to incentivize production in-state. “The motion picture and television industry is responsible for 191, 146 direct jobs and $17.0 billion in wages” in California, according to the Film Commission of California. In an interview with the Los Angeles Daily News, Louis Friedman, producer of 2013’s Lone Survivor, believes production planning around tax credit is “’the single most important financial decision made” and it “affects both the creative look and financial bottom line from day one.’” This production season is bread and butter for the highly skilled – and highly populated – pool of artists, technicians, and other crew people in the state.

However, that legislation has served as a model for other states’ and regions’ incentive programs to surpass. In California, the program was “crafted with limits, from a $1 million minimum to $75 million maximum [in regards to overall budgets] on feature films, and further restrictions on drama series,” not to mention a lottery system that deals with the high demand. This leaves out a lot of areas of production, as major tentpole films’ budgets soar higher and higher and TV shows take bigger and bigger slices of the market. Sensing this sitting-duck situation, the film lobbies of other regions responded.

Canada was the first big player to encroach on Hollywood’s territory in any serious way, putting into law their first production tax incentive in 1997 (just one year after the “all-time high in 1996” of film productions in Los Angeles, noted by FilmWorks). For awhile, Variety reports, “it was only lower-budget series for cable that set up shop outside of Southern California…usually in Canada…[b]ut now the network-studio congloms play a kind of incentive sweepstakes” and pit California cuts against out-of-state cuts. As Variety points out, “these days studio chiefs insist that filmmakers…take advantage of out-of-state incentives…[whose] savings are crucial in a franchise-obsessed era when big-budget movies commonly cost north of $200 million to produce.”

States like New York, North Carolina, Louisiana, Michigan, and many others got into the game. Kevin Klowden, director and managing economist at the Milken Institute’s California Center, estimated a total loss of “4500 production jobs…between 2005 and 2012,” compared with the “7900 production jobs the state should have gained during that period.” New York now has a $420 million annual cap on tax credits, compared to California’s $75 million cap, and has begun to offer additional incentives for productions that complete post-production work in New York as well. Stan Spry, founding partner of up-and-coming management and production company The Cartel, knows this reality very well: “Tax incentives and rebates have been a massive part of our financing plan. We’ve been able to finance up to 40% of production budgets due to incentives…why stay in LA when you can save almost half the money somewhere else?”

Another industry professional, Michael Karnow, creator of SyFy’s Alphas, mentions for that show “we shot in Toronto to save money,” but out-of-state locations “could end up being an asset. It can turn out to be very exciting to turn a problem into an opportunity, and not only let the benefits be financial, but creative.” He mentions Breaking Bad as such an example, one of the most groundbreaking shows of the last decade…almost completely shot in New Mexico, and tailored specifically to the state. It’s interesting to note the original pilot of Bad was written to take place in Southern California…until AMC heard those incentives calling.

This competition, though, now faces the same question that California does: what exactly are the economic benefits of these incentive programs? Other states and countries realized Hollywood was a state of mind, and put into action measures to replicate that mindset for cash-desperate filmmakers. At its peak around 2010-2011, 42 states were offering over $1.4 billion combined in tax credits to productions, hoping to reap economic gains. However, it helps to recall that California’s incentives were built to keep productions inside of its already-developed infrastructure, not to lure runaway production away from Michigan or New Mexico. Historically, California remained the center for production because it housed the developed pool of workers, artisans, and talent, aged like fine wine. Other states don’t have that history, and therefore may not have the job force or economy in place that would benefit from film and television productions.

Take Michigan: leading up to 2011, $57 million had been given out annually to productions each year, with high profile movies like Oz, The Ides of March, and Transformers 3 basing their filming in the state. The problem here became that the Michigan Film Office did not have to disclose the true costs/benefits of the program. Responding to fervent state government criticism, who believed the program wasn’t bringing the economic growth its proponents promised, the program was scaled back in 2011, capping total credits at $25 million and changing the classification of the credits from tax breaks to grants. Michigan legislature, led by Gov. Rick Snyder, now “obligates the [Michigan] Film Office to report back on the specific movie projects that it finances; and to openly declare the criteria it uses to award subsidies,” according to the Tax Foundation. Snyder argues this new criteria makes transparent expenditures that were once “hidden in the tax code.” The Tax Foundation analyzed Michigan and other states’ specific programs, and ruled the incentive programs “distort[ed] the allocation of resources, provide[d] only temporary jobs and benefit[ed] special interests at the expense of the taxpayer.” Other states have scaled back recently as well, with only 35 states offering incentive programs currently.

However, there’s still been a huge increase of programs spanning the globe, and California and its competitors face a race to the bottom. New Los Angeles Mayor-elect (and therefore Prime Minister of Hollywoodland) Eric Garcetti is well aware of this possibility. “’We lost feature films. That’s sad. They may come back to some degree, but probably by and large won’t.’” Instead of competing neck and neck for the most generous incentives, Garcetti wants California to stay ahead of the curve, focusing on creating an environment for a wider spectrum of media production. His plan is to remove the $75 million cap, and make incentives a more viable option for premium cable shows, commercials, visual effects, and even videogames. Garcetti admits he’s seen unfavorable studies, projecting the state seven cents on every incentive dollar spent, but believes there is an unseen multiplier in effect due to California’s historical place as the home of production, and that productions spur economic activity up to five times that incentive dollar’s worth.

Garcetti has charmed his way into many meetings in Sacramento already, but he is facing strong opposing arguments from other neglected California groups. A coalition, made up of the MPAA, the Directors Guild, the Teamsters, and the IATSE artisan union, will work to “win over powerful [opposing groups]…such as the California Teachers Assn.” Groups like the teachers believe more Hollywood tax cuts are merely “giveaways to the glitterati,” similar to the arguments that shut down other states’ programs’ momentum. The Tax Foundation rebuffs Garcetti’s and groups like FilmWorks’ arguments about the film and TV’s key place in states’ economies, believing state legislators should make sure they’re not just lining the pockets of “one particularly vocal and connected industry.” While it is certainly true that the Clooneys and the Spielbergs don’t need much pocket padding, California is a unique economic home of the production worker, and Garcetti wants to make sure it stays their home. An ally, assemblyman Mike Gatto, quoted in Variety, says, “’incentives offer a return on investment that has more to do with individuals’” than studios. “’This is about the regular, workaday people who make a living from production.’”

Despite questions of its long-term economic worth, California undoubtably has a large group of uniquely skilled workers that are facing the possibility of major disruption and possible migration. Garcetti’s planned innovations are important to the future of the state now that Hollywood has proved to not be as stationary as it once appeared.

Interviews with:

Stan Spry, Co-Founder and Head of Production, The Cartel Management & Production, West Hollywood, California

Michael Karnow, writer & creator of SyFy’s Alphas, Venice, California

Other sources:

MPAA, State-by-State Statistics http://www.mpaa.org/policy/state-by-state

Tax Foundation, http://taxfoundation.org/blog/filmworks-blog-criticizes-tax-foundation-industrys-dependence-film-tax-credits

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.