Opportunists taking legal risks to wedge into marijuana business say uncertainty offers a nice middle ground for startups before high rollers come around

Having ditched Morgan Stanley to work in the weed business, Derek Peterson was pretty confident he’d made a good bet when his company ran close to an IPO in 2011.

A year earlier, the former Wall Street banker quit his job and founded GrowOp Technology after he learned a friend’s marijuana dispensary was clearing $18 million a year. California-based GrowOp, which started its business in March 2010, manufactures and sells indoor hydroponic and agricultural equipment to cannabis growers. Peterson reaped $800,000 in revenue in the first nine months. And the business looked so promising that he told Bloomberg his sales goal would be $2.5 million and $5 million to $8 million in the two years to come. He revealed in the same interview that his company was poised to go IPO by the end of 2011.

That IPO plan was never materialized. The startup eventually managed to go public through a reverse merger in 2012, but hasn’t been able to secure significant funding until early this year — all because of legal swings.

“Because the federal government has come to be more supportive, and because they are allowing banks to do business with us now, and because they are not cracking down anymore, the industry is allowed to move forward,” says Peterson.

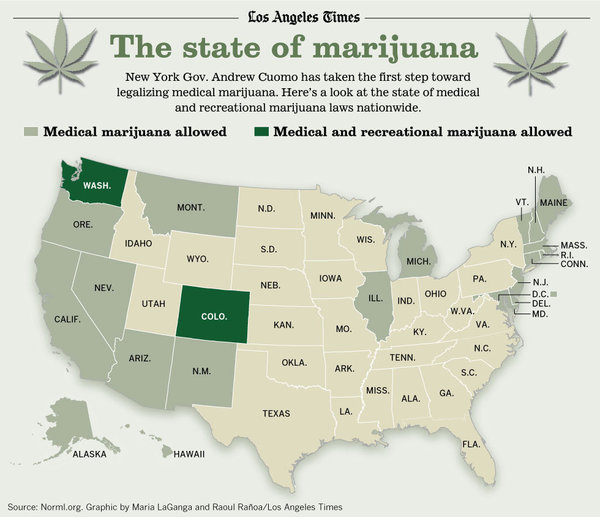

For fear of legal pitfalls, cannabis-related companies have treaded on thin ice for years. Their hands were tied because investors with deep pockets wouldn’t go against federal law to finance weed businesses. Recent passage of recreational use of pot in Washington and Colorado has rejuvenated the market, driving investors’ appetite up. And some pioneering entrepreneurs have learned to sail through the murky legal water.

* * *

Back in 2011, GrowOp’s IPO plan fell short mainly due to an unfriendly political environment. Fifteen states had legalized medical use of cannabis, yet California was cracking down on dispensaries. Worried that the SEC wouldn’t let the IPO come to fruition, Peterson backpedalled. The offering plan had reached its auditing stage.

“Judging from all the pressure that was melting from the federal level, it seemed to us that we might not be able to go public through an IPO, and we don’t want to risk that,” says Peterson.

GrowOp ended up merging with Terra Tech Corp, a listed shell company that does no real business. Peterson and his colleagues took over the management and resumed day-to-day operation. “It’s kind of a back-door channel which goes around the expensive and cumbersome process of going through IPO,” says Peterson. “We think we’ve made a smart decision.”

GrowOp’s story shows how political clout can put off investor sentiment, leaving a dent on startups’ financing ability. But the legal stakes are higher than that. The fact that states and the federal government take opposing stances on weeds has left many investors and entrepreneurs wary about tapping into this niche market. Goldman Sachs and its peers have kept people like Peterson at arm’s length because they could be punished for lending money to cannabis-related companies. Or, if the federal government chooses to come down harder, law enforcement may simply show up at Peterson’s doorsteps and seize all of GrowOp’s assets. For Goldman Sachs, that means loads of money going up in smoke overnight (given that they do care).

Again in 2011, the media touted a “green rush” in the cannabis industry, but the market underwent ups and downs in years followed.

With a net income of $1.2 million in 2010, California-based General Cannabis once sought to raise $10.5 million in an IPO a year later. The technology-based service company with a focus then on the legal pot business was founded as early as in 2003, and began trading some of its stocks on OTC markets in 2010. During its heyday, the company owned seven subsidiaries, including Weedmap.com, an equivalent of Yelp in the world of marijuana dispensaries. It managed 14 medical cannabis clinics in California, and was processing $2,200,000 worth of transactions in March 2011.

But the company sold off its weed business once and for all at the end of 2012 after consecutive slumps in its shares. It also changed company name into SearchCore, Inc. shortly before sales of its pot-related assets.

* * *

Medical marijuana use is already legal in 20 states and the District of Columbia. Recreational use of marijuana was passed in Colorado and Washington in 2012. But under federal law, cannabis has always been treated no different from heroin or cocaine: it is highly addictive and has no medical value, therefore should continue to be banned.

Even in places where medical use of marijuana has been legal at state level, operating costs and rigid regulations make it tough to stay in the business.

In Colorado, legislators have completely freed up weed. The number of medical marijuana businesses there peaked at 1,131 toward the end of 2010 as the drug was being funneled in bulk into the mainstream market from the black one. But the number has dropped to 675 two years later, which equals a more than 40 percent shrink in the industry, says Denver Post. Heavy regulations and police crackdowns have forced a big chunk of practitioners to leave: Stores near schools were forced to close after the state’s U.S. attorney warned that they could be prosecuted if didn’t move. Others collapsed because federal rules denied marijuana businesses of bank loans or common tax deductions.

What adds to the financing hurdle was a big upfront cost that goes into a medical cannabis dispensary even before it opens its door. Jeremy Kelsey, owner of a medical marijuana outlet in Seattle, told NPR that his facility needed bulletproof glass and a 24-hour monitoring system. He spent heavily on ventilation, dehumidifiers, air movers, and air conditioning units — all for producing high-quality cannabis.

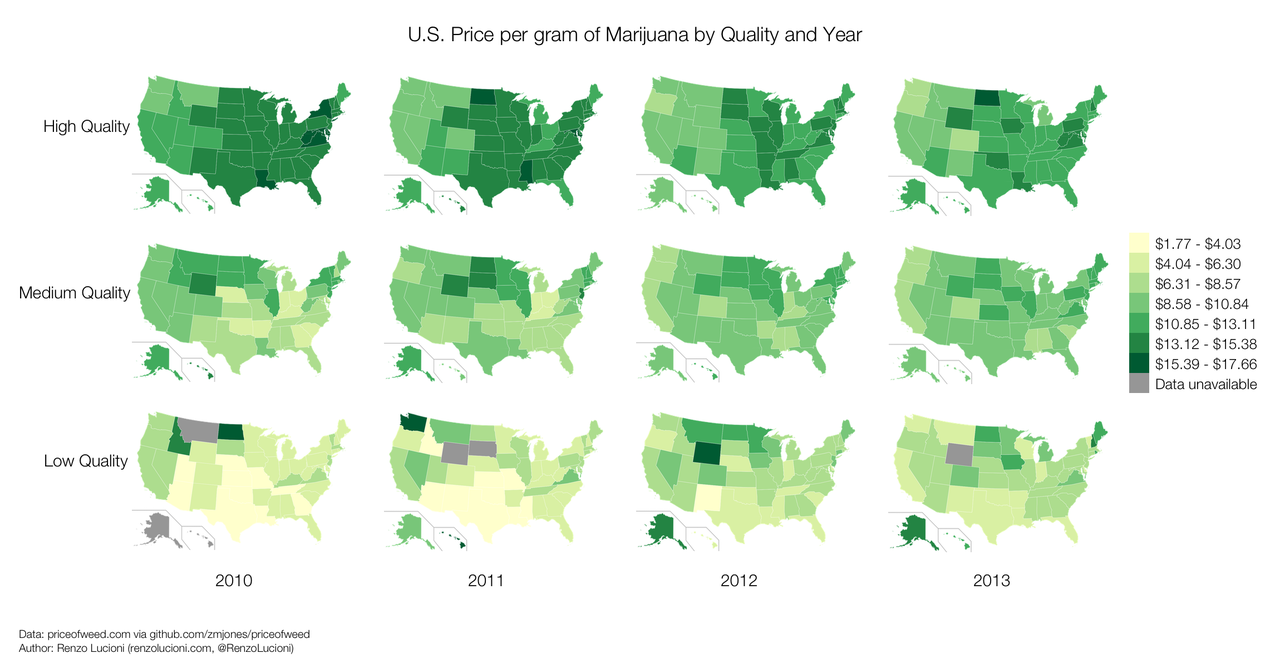

Fluctuation in retail price is another vexing problem. Transaction data collected anonymously by priceofweed.com show mixed results of changes in pot prices in the past three years. There have been drops in the prices of high-quality cannabis, whereas price of low-quality breeds has been marked up.

* * *

One piece of comforting news for weed growers is that the market is gaining new traction after voters made recreational use of cannabis legal in two pioneering states. Nationwide, new marijuana-related legislation is pending in 17 others. Investors are looking at a market that is expected to reach from $1.5 million to $6 million by 2018.

Washington and Colorado are at the very forefront of this rapid growth. In Colorado, pot storeowners cheered for a total of roughly $5 million in sales revenue during the first week selling recreational weed. The retail price of marijuana there has doubled in that week. Seattle-based Privateer Holdings, an equity firm led by two former Silicon Valley bankers, is buying up warehouses in Washington with the $7 million they’ve raised three years into their weed business. They are confident about bringing in roughly $50 million this year alone.

GrowOp, now a subsidiary of Terra Tech Corp, is acting fast to capitalize on Washington’s marijuana reform. It announced in May last year the opening of a new location in Seattle. It is also vying for permits to open marijuana dispensaries in Nevada in hopes of becoming a cannabis grower itself.

“In controlling the actual product that goes for sale at $3,000 to $7,000 per pound wholesale, there is huge amount of strength being the core cultivator,” says Peterson.

The company has just closed a $6.8 million round of financing with Dominion Capital. It also had another $8 million raised from issuing new shares. “The more healthy the political scene gets for us, the more investors come in, and the easier and cheaper it gets for us to raise money,” says Peterson.

He says current legal environment is in fact helpful for GrowOp to get on track to become the Starbucks of weed.

“If it were fully legalized and there’s no legal risks, the big boys would be getting into it. Fortunately this quasi-legal environment provides enough cover for us that the big people will stay out and give us the ability to build market share and our brand,” he says.

He’s right in a sense that the market is already booming with private investors brimming with confidence. ArcView, a California-based organization that connects investors with entrepreneurs in the cannabis industry, has helped its clients secure 4 million of financing in the past few months. The company nearly went out of business two years ago due to a lack of investor interest.

And the money is not only going into selling pot, it’s been poured into ancillary goods that are being built around it. Colorado’s law requires that pot be sold in child-resistant containers, so Ross Kirsh invented Stink Sack, a startup that sells odor-proof packages for weed. He sold his idea immediately to a group of ArcView investors, and was put on a plane to China with the $150,000 he’s raised right after the meeting.

Earlier this month, the federal government issued guidelines on how banks interested in the cannabis industry may navigate the murky legal waters.

“I think you’re gonna see the smaller and regional banks jump in first. As soon as the big potatoes see there is money to be made there, bigger banks will follow,” says Peterson.

To view an infographic on marijuana in America, click here; To learn how weed got in the U.S., click here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.