When wealthy, western nations in Europe joined the United States to enact environmental laws that incentivized the use of vegetable oil in fuels, it was hard to see if there was a crisis on the horizon. These regulations mandated that fuel producers mix in soy, palm, and other vegetable oil with diesel fuels in the name of environmentalism and conservation.

When wealthy, western nations in Europe joined the United States to enact environmental laws that incentivized the use of vegetable oil in fuels, it was hard to see if there was a crisis on the horizon. These regulations mandated that fuel producers mix in soy, palm, and other vegetable oil with diesel fuels in the name of environmentalism and conservation.

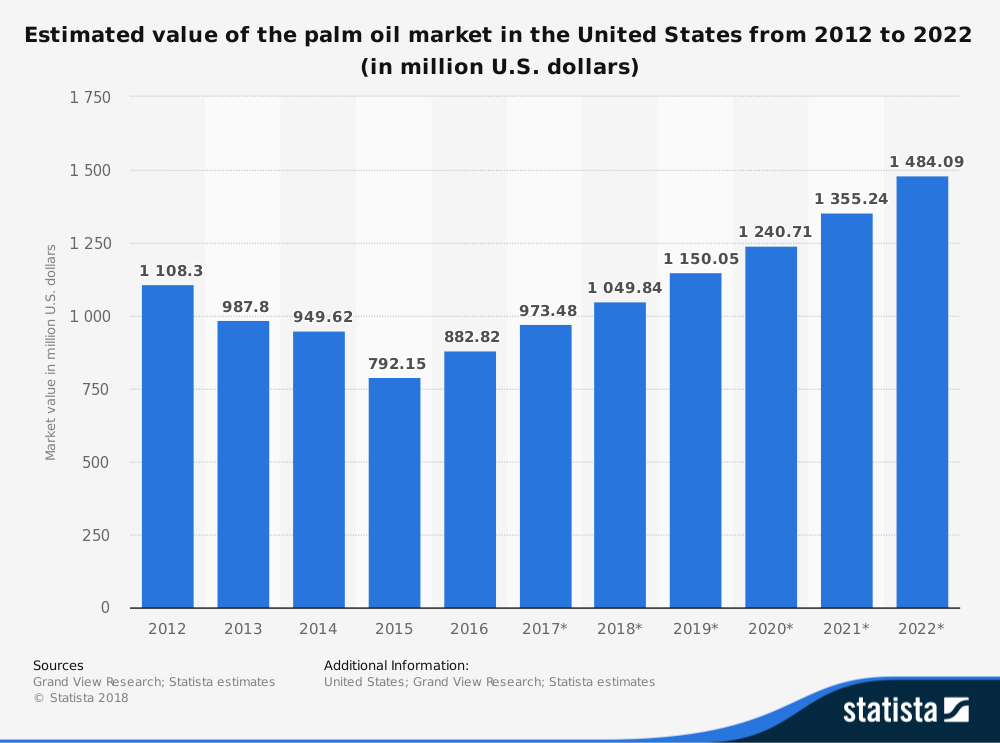

A demand for palm oils soon took off. In response, plantations in nations such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei rose to meet that need. While Palm oils can be harvested in other parts of the world, Indonesia and Malaysia produce 86 per cent of the world’s supply. Biodiesel production within the US grew as well- from 250 million gallons in 2006 to more than 1.5 billion gallons in 2016.

Palm oil is cheap to produce- as the plants produce a large amount of oil relative to their size. The oil also has other uses beyond biofuels and can be found in a variety of shampoo, candles, lipstick, bread and chocolate.

While developed nations were able to benefit from the use of alternative fuels, other countries have continued to deal with environmental impacts of the industry. Indonesia has lost over 38,000 square miles of forest in just 30 years, and has become the fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in the process. Why is that? The forests of Borneo, an island that is home to parts of Malaysia, Indonesia, and the nation of Brunei, spans large peatland swamps, and the destruction of those forests was roughly equivalent to the opening 70 new, large coal-fired power plants.

The demand for Palm Oil also changed the economic relationship between local farmers and their ownership of the land. The growth of massive plantations has also consolidated land from hundreds of local farmers. While the development land sharing process in Indonesia had been developed to allow local villagers to share in the profits of development, many were faced with intense lobbying, bribery and strong-arming, and missing payments.

Some land agreements missed the consent of local residents altogether. Gusti Gelambong, a resident of the Kalimantan region in Indonesia, explained to the New York Times that microfinance corporations gained control of the land by doctoring lists of signatures on contracts, even using the names of residents who had long passed away.

Because of the land-sharing development agreements, almost a third of Indonesians depend economically on palm oil as nearly half the industry consists of individual landowners. And that is where the conflict between what is economic benefits and environmental costs arises. While the EU parliament has called to phase out palm oil from transport fuel by 2030, countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, so heavily demand on the production of palm oil despite environmental concerns.

“If you pull out biofuel, the whole system will collapse,” said Dono Boestami, the director of Indonesia’s Palm Oil Development Fund.

However, if Indonesia’s production of Palm oil depends on the destruction of forestry that regulates the release of carbon from peatlands, whic collapse will matter more to the global economy: an environmental collapse or an nationally economic one?

Sources:

https://features.propublica.org/palm-oil/palm-oil-biofuels-ethanol-indonesia-peatland/

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/nov/02/displaced-villagers-myanmar-at-odds-with-uk-charity-over-land-conservation-tanintharyi

https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/palm-oil

Oil Palm, The Prodigal Plant, Is Coming Home To Africa. What Does That Mean For Forests?

https://features.propublica.org/palm-oil/palm-oil-biofuels-ethanol-indonesia-peatland/

https://af.reuters.com/article/commoditiesNews/idAFL8N1TG4J1