The grip that McDonald’s has on the fast food industry is currently being challenged—not by a competitor, but instead by a labor crunch. The company is adding new technology in its restaurants to adapt, and as long as these renovations are successful, competitors will likely follow suit.

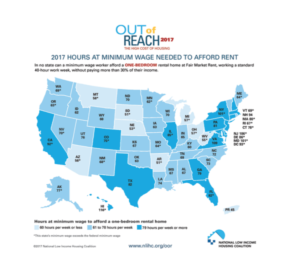

In recent years, McDonald’s has been unable to meet consumer demands, in large part because of the current labor landscape. First, there’s the rise of the gig economy, where workers can spend the day putting together someone else’s IKEA furniture through TaskRabbit instead of working a cash register. Second, minimum wage is increasing across the country, which means it’s harder for companies to afford enough employees to make their businesses run.

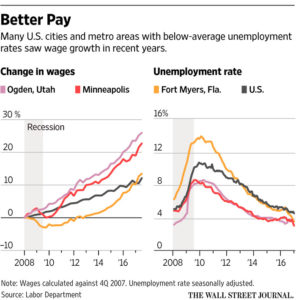

Plus, due to low unemployment, the labor market has changed dramatically. While a high employment rate is typically considered positive since it increases our country’s capacity to produce, it also means that businesses looking for workers will have a harder time finding them. This trend hurts fast food companies in particular, since jobs in the industry are often seen as less desirable compared to other options that offer higher pay and better benefits. The current economy favors workers, who can pick and choose where to work—and fast food restaurants often aren’t their first choice.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

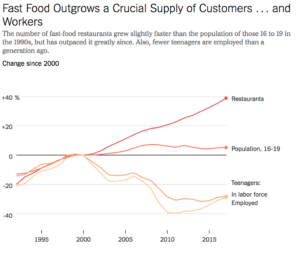

In addition, less teenagers are working, which hurts the fast food industry in particular. In 2000, 45 percent of young adults aged 16 to 19 had jobs, whereas today, only around 30 percent do because more students are focused on their education. Teenagers historically provided cheap labor that fast food relied on, but now that source of labor has decreased drastically.

Source: The New York Times | Bureau of Labor Statistics

There were 898,000 open jobs in the accommodation and food services industry in August 2018, which was 20 percent higher than August 2017, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. If unemployment says low, we can expect the number of vacant positions in fast food to continue growing.

This market also means it’s harder for fast food chains to retain workers. Workers are quitting at the highest rate in over a dozen years, and the turnover rate in the restaurant industry at large was 133 percent last year, according to TDn2k, a restaurant research firm.

To address the changing labor landscape, some companies have raised their wages. In 2014, fast food wages began to increase and have risen at a higher pace than overall wages in the U.S. ever since. In May 2018, the owner of one Chick-fil-A store made headlines when he decided to increase pay of his workers from $12-$13 to $17-$18.

Instead of increasing wages—which McDonald’s promised to do in 2015 at company-operated stores but has failed to deliver on—the fast food giant has found other ways to entice employees. In October, the company announced an innovative career advising program. According to Stephanie Chan, who oversees the company’s Brand Reputation in California, Arizona, and Nevada, McDonald’s has also grown its career services department so that assistance “isn’t just being offered to employees themselves—it’s open to their immediate family as well.” Earlier this year, the company also announced that it was allocating $150 million to its education program and lowering the eligibility requirements, allowing an additional 400,000 employees to be eligible for tuition assistance and high school diploma programs.

Archways to Opportunity, the company’s education opportunities program, provides a variety of benefits to McDonald’s employees. Source: Archways to Opportunity.

In the long run, the trouble that companies are having hiring and retaining workers hurts customers, since new workers or fewer employees means that the quality of service worsens. According to the American Consumer Satisfaction Index’s national measure of consumer happiness, on a sale of 1 to 100, consumer moods have slid from 77 in the first quarter of 2017 to 76.7, where it has sat for all of 2018. The Index reports that this is “the longest period of stagnation since 1993.”

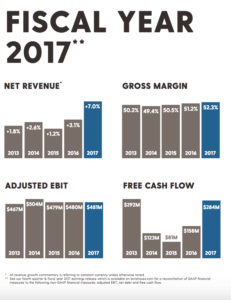

As a result of growing dissatisfaction, American fast food restaurants have less foot traffic and have become less profitable. In September 2018, there were 2.6 percent less people visiting fast food stores than a year ago, which means fewer opportunities to sell food. At McDonald’s, revenue was 7.32 percent less in 2017 than in 2016, which followed a 3.11 percent decrease from 2015.

This decline in customer satisfaction is partially an outcome of higher expectations. Recent growth in the restaurant industry means customers have more choices when deciding where to eat, which has led to fierce competition. In a recent survey, 26 percent of U.S. consumers said that because they have so many dining options, they have higher expectations than they did two years ago.

Customers also have higher expectations in terms of the food production process. As a result of demands for better ingredient quality and less animal cruelty, companies have already been forced to adapt. After Panera Bread and Chipotle Mexican Grill led the way, chains like Chick-fil-A, Burger King, Taco Bell, McDonald’s, and KFC instituted policies that would limit antibiotic use in poultry. Plus, McDonald’s announced a few years ago that it would use 100 percent cage-free eggs in the U.S. and Canada by 2025.

Source: The Center for Food Integrity

The company also announced earlier this year that it would start making fresh beef quarter-pounders rather than relying on frozen meat. Evette Gonzales, a McDonald’s store manager in Los Angeles, said that her location in Century City is “selling more quarter-pound beef since we changed over.” In fact, sales at her location are up 5 percent this year, which she largely credits to the introduction of fresh patties.

Consumers are also requesting lower prices, causing many stores to offer discounts and deals. At McDonald’s, this has taken shape in the revamped Dollar Menu, which launched in early 2018 and features $1, $2, and $3 options. Plus, back in 2015, McDonald’s started offering breakfast all day after years of pressure from customers.

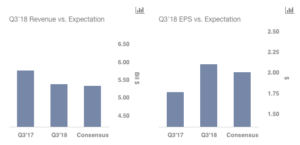

All of these tactics to meet consumer needs seem to be paying off. In the company’s most recent earnings report, which came out at the end of September, same-sales stores growth went up in the U.S. and internationally, although the 2.4 percent increase in same-store sales in the U.S. was actually fueled by higher prices, driven by increased commodity costs. Additionally, the earnings report shows a 7 percent decrease in revenue and a 13 percent decrease in net income compared to a year ago. Despite these seemingly-negative figures, the company largely beat expectations from analysts, who assumed that the company’s earnings per share would be at $1.99 but instead came in at $2.10, and that revenue would be around $5.32 billion instead of $5.37 billion. Therefore, while McDonald’s is still not performing as well as it has in the past, the fact that the company outperformed some projections shows that their tactics may be working.

Quarter 3 expectations and results from 2017 and 2018 for revenue and earnings per share. Source: Terifs

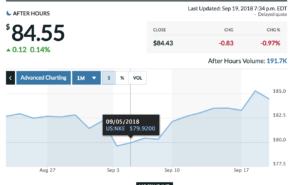

This largely positive quarter stands in strong contrast with how McDonald’s was viewed by investors earlier this year. In June, the company was on its way to becoming the worst performing in the DOW in 2018, in large part because shares dropped dramatically in March after the Dollar Menu brought in uninspired results. Since then, the company has rebounded.

Stock price of McDonald’s Corporation over the course of 2018. The company took a hit after lackluster sales from its Dollar Menu, but has managed to recover ahead of 2019. Source: Google Finance

Despite these tactics to appease customers, and the steps taken to attract and retain employees, larger trends have weighed heavily on McDonald’s. As a result, the company has separated itself from competitors by taking more drastic action.

It’s called “The Experience of the Future,” a remodeling plan that was supposed to be completed by 2020, but was just pushed back to 2022 because franchises believed the previous timetable was unrealistic. The remodels will include self-order kiosks, new systems for delivering orders, and extra drive-thru lanes. Additionally, over 12,000 stores will have digital menu boards, more parking spots for pick-up, and expanded counters and display cases. Beyond this initiative, McDonald’s has already invested in its mobile ordering and payment system, which is currently operating in 20,000 stores, and introduced delivery through a partnership with UberEats.

A customer using a self-order kiosk at McDonald’s. Source: Bloomberg

The price tag for the project is big —in August, the company announced that in addition to what it had already set aside, another $6 billion would be put toward the modernization process. While the technological advancements are certainly costly, McDonald’s sees them as an investment that will pay off. Although few stores have received their makeovers, given how much McDonald’s is devoting to renovations, investors are bullish about the stock heading into 2019.

However, opinions diverge on exactly what is the driving force behind the massive renovation project.

According to Shon Hiatt, a Professor of Business Administration at the University of Southern California and expert in the world of fast food, investmenting in technology “is a fantastic way to address the labor cost issue—they don’t need nearly as many people.” With greater technology integrated throughout the restaurants, Hiatt predicts that McDonald’s will reduce the number of employees. This makes sense given the current labor market—right now, it’s hard to find workers, plus thanks to the rise of minimum wage, companies are devoting more and more money to afford their staff. Through technology, McDonald’s can put that revenue to use elsewhere.

However, this change will likely have dramatic implications in the long-run. If companies cut employees as the move toward automation, Hiatt cautions that will increasingly “displace those who are the least qualified in terms of having a job,” taking away their minimum-wage position and throwing them into the job market with the subpar skills one learns flipping burgers. At the same time, Hiatt notes that a low-paying job like one at McDonald’s at least provides an opportunity to learn transferable skills like customer service and sales. Without that possibility, many individuals will have even less of a chance to dig themselves out of systemic poverty.

Those inside McDonald’s tell a different tale. Chan said the move toward innovation is focused on “meeting customers where they are at” and listening to their preferences, not a labor crunch. She said that the focus of the innovations is on “putting more choice in the hands of guests—evolving what they order, how they order, how they’re paying, and how they’re served.” While many believe that self-serve kiosks will take away jobs, Chan says the opposite is true—stores will have to “increase jobs because with the introduction of the kiosk, it introduces several new positions into the restaurants” including a team member to show customers how to work the technology. In Century City, Gonzales agrees that “the technology actually calls for more employees, because customers are afraid of how to use the screens.”

Despite these arguments, employing technology instead of people seems to be the way the industry is moving, given comments made last year by Yum brands CEO Greg Reed. Even if the argument made by Chan is true now, one is still left to wonder whether the positions created by the technology will last. Once customers learn how to use the ordering devices—which most people know how to do already—that job could easily vanish, along with others that are no longer necessary in the redesigned stores.

Whether the main driver behind the investments is rising labor costs—which, given the evidence, seems likely—or changing consumer demands, or some combination of both, McDonald’s is forging ahead with technology in hand to do what it has deemed necessary to save its business.

This McDonald’s in Sydney, Australia is an example of what renovated stores may look like across the U.S. Source: Fast Company

While it’s unclear how customers will respond to the renovations and if McDonald’s will turn higher profits as a result of them, one thing is for sure: if any fast food company is suited to address the challenges headed their way, it’s McDonald’s.

Although competitors are starting to invest in automation, and have begun offering greater employee benefits and discounts for consumers, no other company is investing as heavily in its future as McDonald’s is right now. In her past year working for McDonald’s, Chan has seen that “there’s innovation happening constantly throughout the company—whether that’s with technology, the food, what we are doing with our people. There’s a constant forward movement.” As a result, she believes that whatever comes next, the company is well-suited to face it head on.