No one enjoys dealing with rejection, but “no” can be especially difficult to cope with when it concerns someone’s health. Brittany Smith*, who was diagnosed with Type I diabetes in 2012, knows this to be true. “I didn’t cry when I found out I had diabetes, “ Smith said. “But I found myself sobbing to the pharmacist at the back of a CVS the first time I couldn’t get the medication I needed.” Diabetics rely on the proper medication and medical devices to constantly monitor and maintain healthy blood glucose levels. Smith must constantly replenish lancets, test strips, and needles. In spite of her diligent efforts, a miscommunication between her family doctor and the pharmacy forced her to choose between spending a small fortune on a different brand of medication, or going without it. “Being diagnosed with a chronic illness is shocking, but you can learn to live with it. My medication is one of the few tings that I cannot live without.”

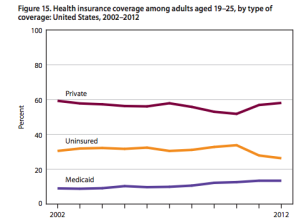

Recent reforms in healthcare law have the potential to simplify medication management and reduce costs for patients with chronic illnesses, like Smith, as well as

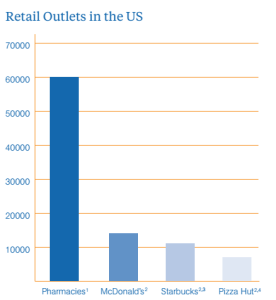

The number of pharmacies is on the rise, but people may not realize it. People do not notice them as readily.

everyday consumers. Provisions in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), affectionately known as ObamaCare, create financial incentives for providers and insurers to improve patient outcomes and reduce overall costs, as opposed to rewarding physicians based on the cost of services and medications. Healthcare payers are responding to these incentives by working with retail pharmacies to expand their services and adapt the role of pharmacists. Companies like Walgreens, Rite Aid and CVS are aggressively investing and trying to expand their retail pharmacy businesses. Their goal is to make healthcare services cheaper and more convenient for consumers, while also providing medication counseling. At they same time, they are helping to meet medical service demands that the current infrastructure cannot support well, while still turning a handsome profit. Healthcare payers are please because they will now benefit financially from improving patient outcomes. The nation should feel the same way, given that this model has strong potential to lower the unsustainably high cost of healthcare. Expanding retail pharmacies is not just a win-win situation, it’s a quadruple win. It is remarkable that this scenario could arise simply from properly aligned industry incentives. Is it too good to be true?

Time will tell, but the present is filled with promise. The changing healthcare landscape and the retail pharmacy model are poised to improve the consumer experience and better meet demands. The revolution will not come easily; healthcare retailers will face substantial competition from aggressive competitors and will remain beholden to price factors beyond their control. For consumers, however, the change has lasting transformative potential.

Why Now?

Retailers have compelling economic reasons for investing in or expanding their investment in the retail pharmacy space. They anticipate increased demand for healthcare because of the ever-aging population and because 30 million new customers are expected to enter the healthcare market thanks to Obamacare. Data indicates that  consumers will buy more services if they make them cheaper and more convenient. A Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) study found that many people decline to pay for some preventative care solely because of cost. By reducing the costs, retail pharmacies can recapture that lost business while improving public health.

consumers will buy more services if they make them cheaper and more convenient. A Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) study found that many people decline to pay for some preventative care solely because of cost. By reducing the costs, retail pharmacies can recapture that lost business while improving public health.

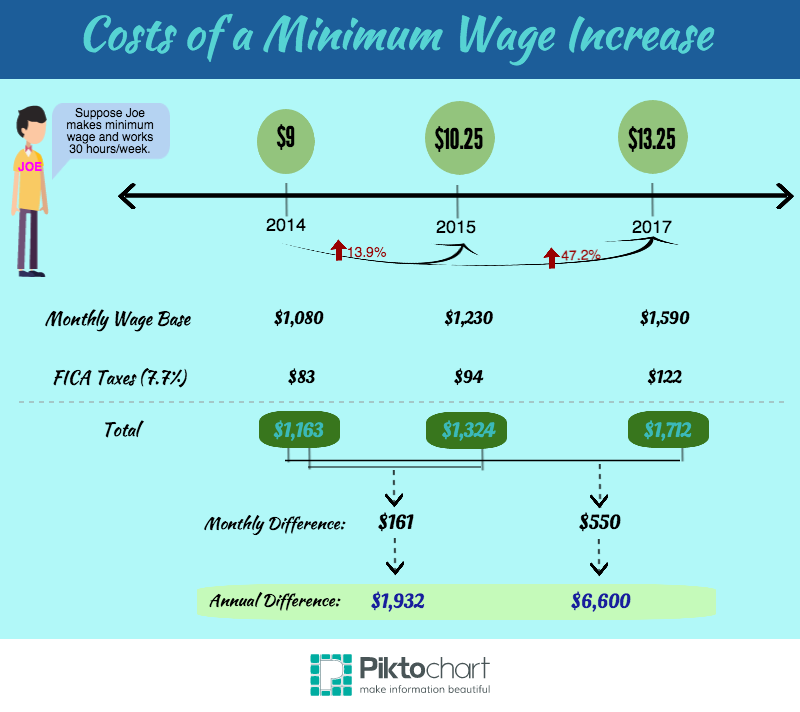

The time is ripe for the rise of retail pharmacies. Americans have begun taking more responsibility and initiative in their healthcare, albeit not necessarily by choice. Out of pocket costs increased 250% in the last five years. The ACA has led employers to switch to more high-deductible plans. Last year 13% of employers offered such plans, up from 3% in 2006. This change may be unpopular, but passing off costs created an unsustainable burden on the system. Increased deductibles are forcing people to take a more active role in managing their healthcare.

A Promising Prognosis

Retail pharmacies can make services and medications offered under the century-old traditional model cheaper and more accessible. Physicians, depending on the patient’s plan, are reimbursed by insurance companies or the government for volume of business, so the amount they bill directly correlates to their bottom line. In contrast, pharmacies make higher profit margins on generic medications than on more expensive brand names, so they are incentivized to encourage generic alternatives. For example, CVS has gradually increased the amount of prescriptions it fills with generics, rising from 71.5% in 2010 to 83% in 2013. Minor medical services, like administering vaccines, conducting physicals, and treating non life-threatening illnesses, are much cheaper at a pharmacy than at a doctor’s office or hospital. Rapidly improving medical technology makes it easier for pharmacists to diagnose illnesses, expanding their range of services and saving customers expensive trips to the doctor. Visiting a retail pharmacy costs $79-$89 on average, less than half the cost of the typical doctor visit. Picture this: the next time you fall ill, you can drive or walk five minutes to your nearest pharmacy, likely closer than your doctor’s office, get diagnosed, and pick up your medication on the spot. The trip cost you less time and money, and you’re home again before you can say “Uncle.”

In addition, retail pharmacies plan to offer services the current healthcare system cannot provide, such as medication management and adherence. While those terms may not sound significant, they are vital for people with chronic illnesses. Consider Smith, who notes, “When I think of management, I laugh about the ‘I have diabetes, but diabetes doesn’t have me’ phrases. No, it doesn’t run my life or prevent me from doing most things I want to do, but if I want to live a long, healthy life I have to make choices every day because of my illness”. She has to test her blood sugar levels 12 times a day, and administer an insulin shot when necessary. Along with maintaining and carrying a supply of medical equipment, Brittany has to have snacks and glucose tablets with her just in case. She is a model patient, and if every diabetic followed her regimen, the nation could potentially save billions on healthcare costs. Analysts estimate America spends $290 billion on healthcare services that could have been avoided if patients adhered to the medication they were prescribed. There is a clear need to help people manage their medicine, but meeting that need is not practical for doctors. They are dramatically overqualified, so it would not cost effective for them to fulfill this role, nor would it be convenient for patients. In contrast, national retail pharmacies can invest in the technology, like smartphone apps, websites, and backend software to help schedule prescriptions, notify patients when they are ready, and remind them to take their medication. Doctors would be hard-pressed to offer comparable services.

Side Effects

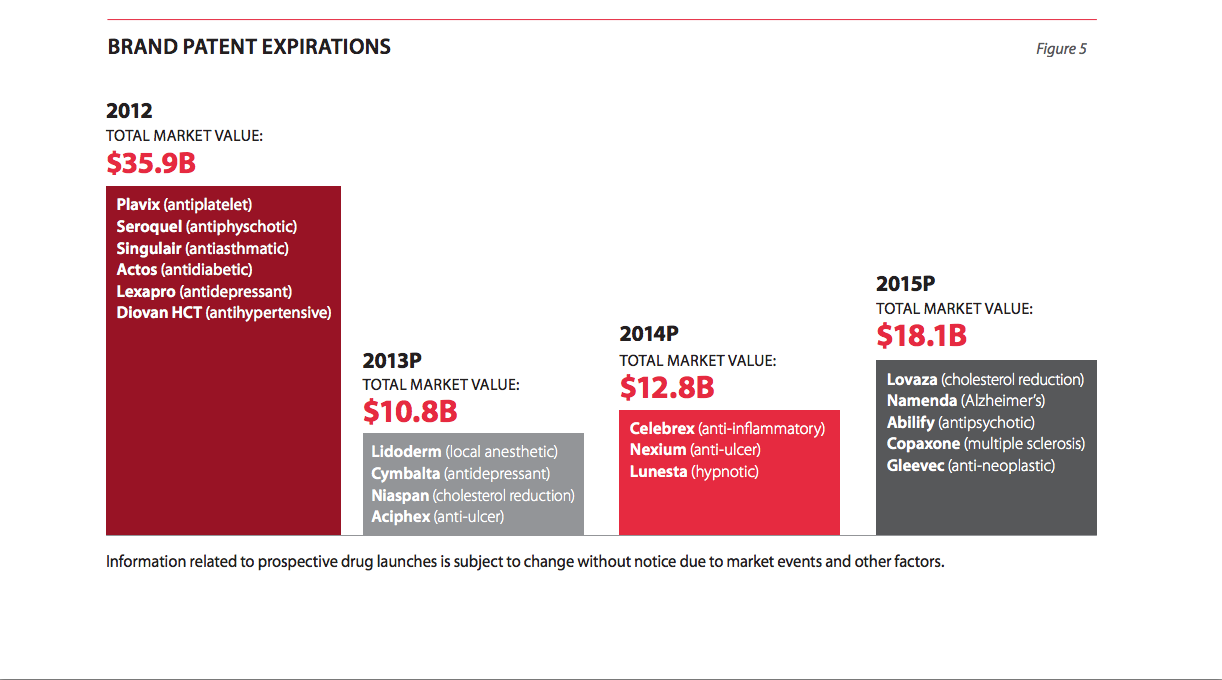

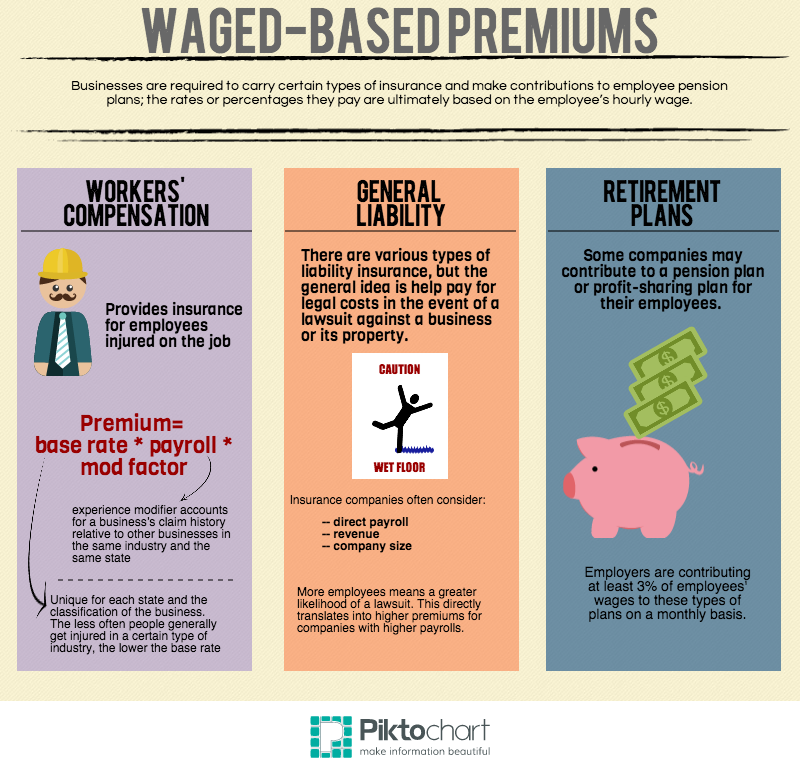

Fluctuations of brand name and generic drug prices have a significant impact on pharmacies’ profitability. They have no way to control significant price fluctuations; the best they can do is plan for them. Brand name drugs are considerably more expensive and are sold on lower margins. Consider that in 2009, generics accounted for only 9% of revenue, but 56% of profits for the biggest three wholesalers, while brand drugs accounted for 88% of revenue and only 38% of profits. The reason for this disparity is that the largest pharmacies can buy generic drugs directly from the manufacturers because they have the negotiating power and warehousing capabilities. They are uniquely poised to do this. Most other generic retailers, including supermarkets, small independent pharmacy chains, and physicians’ offices buy generics through drug wholesalers like McKesson, AmerisourceBergen or Cardinal Health. Nearly every drug retailer purchases brand name drugs through a wholesaler. Switching to generics can help make the retail pharmacy model more profitable, especially relative to competitors who lack comparable negotiating power; however, fewer drugs are expected to go off-patent in the coming years, which means generic substitutes may not be available. Those that are available may not be much cheaper, as the same economic principle applies to generics as to brand names. If they have a monopoly they will exploit it. Generics that are launched with exclusivity are priced just 10% below the reference brand.

Further complicating the economics for retail pharmacies, costumers are less concerned with brand loyalty than they are with cheaper prices. The Walgreens-Express Scripts dispute serves as a reminder of this reality. When the two companies parted ways because of a contract dispute in 2011, Walgreens lost customers and roughly $4 billion in revenue, or about 21 cents a share. Customers left Walgreens, not Express Scripts, because they cannot make decisions about their plan benefit manager, and were not infuriated because they could easily find another pharmacy.

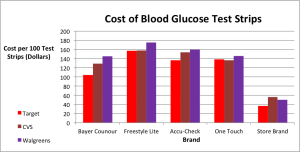

Purchasing test strips adds up quickly. Costs vary among retailers, but, for Smith, not significantly enough to motivate her to sacrifice convenience.

Today’s market is highly competitive. Pharmacies are expanding, making it more convenient for people to go to any one. They all offer the same basic services and range of medications at similar prices, so location is key. Walgreens opened its first location in downtown Los Angeles in 2010, right across from the Rite Aid on 7th and Broadway. In 2013 the company opened its second location on 5th and Broadway, once again right across from a Rite Aid. Walgreens, CVS Rite Aid and the like are making strong efforts to acquire and retain customers. Their websites encourage visitors to create accounts to manage their prescriptions and take advantage of rewards programs. In comparison, Target, which has been less aggressive in its entrance to the market, displays its prices online and makes it easy to compare services. They make less effort to encourage signups, treating health services more like an impulse buy. Target’s profitability depends much less on its pharmacy business than a company dedicated to wellness though. Retail pharmacies must find ways to retain customers in a competitive market, because their services are so comparable that it is difficult for any one to stand out.

***

The retail pharmacy industry is trending in a very promising direction for consumers, which is refreshing given the state of the American healthcare system. There is clear opportunity for companies looking to break into this market or expand their business, but much of their success and profitability will hinge on finding ways to create customer loyalty. Retail pharmacies must generate enough demand in sufficiently large markets to avoid out-competing one another.

There will be more pharmacies in the future. May not hold promise to people with chronic conditions that they can get the specialty medication they need anywhere. But their options are improving, it’s a great start that stuff is cheaper and more convenient. Future will test how well these incentives are aligned.

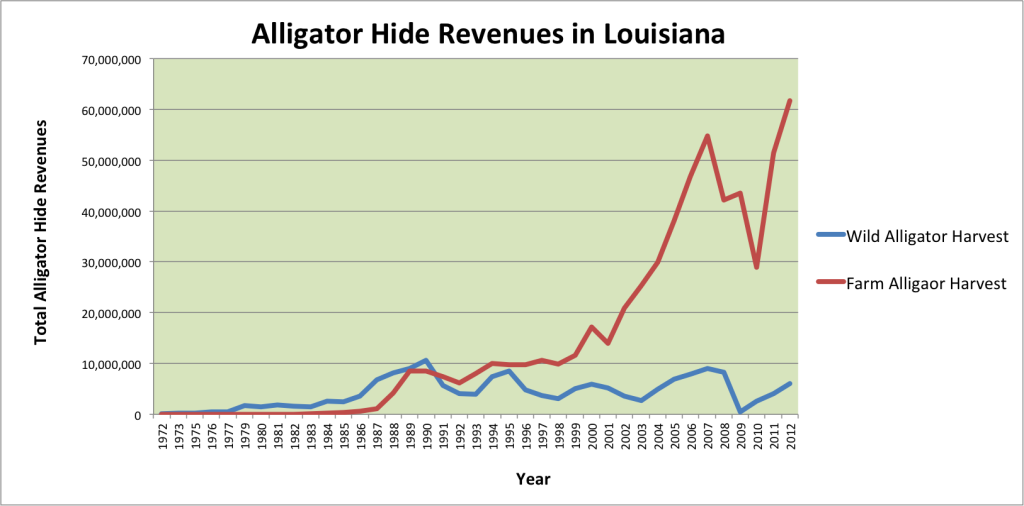

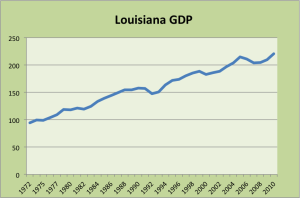

r how well the economy is doing, $2000 for Gucci alligator skin loafers or $100,000 for an alligator skin Birkin bag by Hermes, one of the most prominent players in exotic tannery business, never seems worthwhile. Apparently during recessions the wealthiest Americans are hit hard too—right in their $11,000 Burberry alligator skin wallets; but that’s just fine by the alligator population.

r how well the economy is doing, $2000 for Gucci alligator skin loafers or $100,000 for an alligator skin Birkin bag by Hermes, one of the most prominent players in exotic tannery business, never seems worthwhile. Apparently during recessions the wealthiest Americans are hit hard too—right in their $11,000 Burberry alligator skin wallets; but that’s just fine by the alligator population.