Adam Jacobs, co-founder and Content Director for BuddyTruk – a Santa Monica based startup that aims to be the Uber for people in need of help moving – made a decision most people in their mid-20s would loathe: he moved back in with his parents.

For Jacobs, though, it was merely a byproduct of “tightening up the budget” and taking a chance on being a part of the next big Los Angeles tech startup.

“In [startup ventures], you absolutely have to be willing to take risks,” said Jacobs, while sitting on the rooftop of their office two blocks from the ocean. “I see it as the next step to something that is a huge success.”

Founder Brian Foley had the genesis for the company when he was using a U-Haul to move into his new apartment, and crashed into his roommates car before even meeting her. As he puts it, all he needed was “a buddy with a truck,” and he would have avoided trying to steer such a cumbersome — and expensive — vehicle.

The idea was too good to pass up when Jacobs was approached by a mutual friend about joining the startup, and convinced the 25-year-old UCLA graduate it was worth quitting his “comfortable” job at Apple to pursue full time.

And walking the halls of the office building BuddyTruk shares with more than 100 other tech startups, it becomes clear many more entrepreneurs share Jacobs’s desire to be part of the changing zeitgeist in LA.

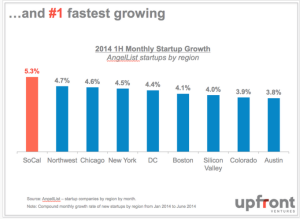

The Company Town that was built on the film and entertainment industry is now becoming one of the premier locations for startup innovation. LA is now the third largest tech ecosystem in the United States (behind Silicon Valley and New York), and the fastest growing market, according to TechCrunch.

Altogether, there are more than 1,000 startups in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, according to company tracker Represent.LA. Silicon Beach is becoming a formidable southern counterpart to Silicon Valley.

While the LA startup scene appears to be blossoming, there remain a myriad of growing pains for companies like BuddyTruk, which launched their app this past August. Development, funding, and acquiring users remain the core roadblocks to success.

“The first two weeks we had two transactions, so it was like ‘ok, there’s a lot of work to do,’” said Jacobs.

Finding a way to get the app name recognized became paramount. Jacobs had to set aside time for “guerilla marketing” by passing out flyers on his old campus.

Things eventually began to turn around with the college move-in season, and the company was featured on TechCrunch and on KTLA 5 in LA. Still, the whiteboard behind Jacobs’s desk outlining the company’s goals for December – 1,500 users, 2,000 Twitter followers, 3,100 Facebook “likes” – highlights the importance and difficulty of simply making your app stand out.

Users are essential to venture capitalists looking to fund these companies in their early stages. For most startups, the game plan becomes: gain a following first, and worry about monetizing afterwards.

Wildly successful LA startups like Snapchat and Tinder understood the gravity of acquiring a large audience before monetizing. Snapchat, valued at $10 billion, only recently began experimenting with short advertisements.

Foley, the gregarious face of the startup, said the business received $175,000 in its opening round of investment, and is now trying to raise an additional half a million dollars. BuddyTruk also met with Target and Costco this month in an effort to provide their service to customers needing large items delivered.

From the outside, everything would appear to be coming up roses for the company: traction, a nice Santa Monica office, and room to grow.

But Foley understands how difficult it is to create a successful startup. The native of Austin, TX started four companies before BuddyTruk. Each one of them failed.

Rather than leaving him dejected, those disappointments galvanized the Pepperdine graduate even more when he was ready to tackle his next venture.

“Each time we ran a company in the past and it failed, I knew exactly why,” said Foley. “So this time around I was more confident than ever raising money and sticking by our mission statement.”

It’s an attitude that entrepreneurs must have to be successful in this industry. Failure is often synonymous with tech startups.

70 to 80 percent of startups fail to see a return on their projected return on investment, according to a study by Professor Shikhar Ghosh of Harvard Business School. And the numbers are even more dire for companies that issue projections and then coming up short of meeting them, with 95 percent falling through.

—

Blake Arnet realizes the high stakes nature of the startup world. His first company, CollegeHop, a social network to connect students with the “most fun and unique places around their area,” floundered.

“You fail a lot before you succeed,” said Arnet. “Building connections and a small company – the whole process was invaluable.”

The experience of starting his own tech company left an impression on the former UCLA basketball player, though. Arnet knew he wanted to get back into the startup world, and recently launched his latest idea.

His latest app, Castoff, allows users to anonymously receive votes and input on pictures from their friends. Arnet believes the idea is more efficient than sending a mass text message, and is perfect for someone trying to figure out what to wear out on the town.

http://youtu.be/rVVYCtFaQDg

Any residual pain from his experience with his first company has been mitigated by the allure of making Castoff a success.

“I’m very optimistic as a person and with the app,” said Arnet, sitting at the Literati Café on Wilshire, two days shy of his 25th birthday. “I think [Castoff is] a great app and if people get it in front of them, they’ll like it.”

Like Jacobs, he’s driven to make his startup work by any means necessary.

Arnet personally split the $20,000 needed to get the app off the ground with his longtime friend and co-founder, Adam Jacobson, and Jacobson’s father. He’s working as a private sports coach, Uber driver, and helping with his father’s construction company in Orange County to give him enough time to work on the app. Coffee shops on the West Side and working from home are Castoff’s office space until further funding.

Funding, along with acquiring users, remains the biggest hurdle. While the venture capital market is rich in LA, it still falls well short of Silicon Valley. A company starting with a well-known LA incubator like Amplify figures to raise about half as much as a company in Northern California.

The high failure rate of new apps, which have been personally monetized, only exacerbates the importance of finding angel investors.

“When you’ve bootstrapped a business where you’re not drawing a salary and depleting whatever savings you have, that’s one of the very difficult things to do,” said Toby Stuart, a professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business to the Wall Street Journal.

To take his company to the next level, Arnet is preparing to pitch Castoff to investors. His goal of $300,000 in seed money would mostly finance the marketing and front-end help necessary to bring Castoff to a larger audience.

Still, the hardest part of being a young entrepreneur can often be simply getting your foot in the door.

“Being first time entrepreneurs, that’s our biggest struggle right now,” said Arnet.

“If you’re a guy like Biz Stone [co-founder of Twitter] you get money ‘like that’ – you get $100 million.”

With the potential funding, Arnet hopes to expand Castoff’s reach to more college campuses, where anonymous apps like Yik-Yak have become increasingly popular.

And while Arnet knew a co-founder he was confident in starting his company with, for others it can be one of the more difficult and time consuming aspects of building a team.

—

The inspiration for Nick La Maina’s app, Tikr, stemmed from an overly excited friend.

“This girl kept posting on Facebook that her birthday was in 50 days, 49 days, 48 days,” said La Maina. “I was like ‘that’s so annoying, she should do this in a countdown app.’”

After researching and noticing the market for a social media app that would countdown to events was relatively barren, La Maina decided to pursue the idea head-on.

But for the 2013 graduate of USC’s Marshall School of Business, there was one main issue: he couldn’t find the right person to start with.

It took countless mixers, hours talking to friends and professors, and working connections to find a match. La Maina compared the experience to dating.

“It was really hard to find someone,” said La Maina. “It too me a year and three months,” to find a co-founder.

The moment was both exhilarating and a relief for La Maina, but there were many other issues to solve. For tech startups, each day is like playing Whac-a-Mole, where one problem pops up the moment another has been taken care of.

Development talent In Los Angeles is growing, but still trails Silicon Valley. Finding a developer for Tikr was a headache, with bids as high as $100,000 to design the app.

As a new company working on a tight budget, La Maina felt it was imperative to get Tikr launched and A/B tested as soon as possible, rather than building the most refined app. Ultimately, he was able to secure a design for under $10,000, and see Tikr featured among the Best New Apps on iPhone’s store.

The rush of growing their user base and trying to bring in additional seed funding makes the high-stress nature of startups worthwhile to La Maina. Like BuddyTruk, Tikr was recently featured on KTLA 5.

“I woke up and there we like 2,000 installs in one morning. It was an amazing feeling,” said La Maina.

La Maina views being an LA startup as an advantage because of its proximity to the entertainment industry. Tikr did a countdown promotion with the History Channel’s Vikings television show and is looking for similar deals.

The 23-year-old is now an associate professor at USC, helping students outline a plan for their own startup ideas. But despite the early success, La Maina is aware the tech startup world is a minefield, and knows the odds are against having the next billion-dollar sale.

“Overall, the app market right now is a really tough one to play in,” conceded La Maina. “People don’t use a lot of apps, they’re tired of downloading them, and to break into someone’s daily habits is a big ask.”

Like other young entrepreneurs looking to make their mark in LA’s startup scene, he knows it’ll take two things – “a lot of hard work and a little luck.”