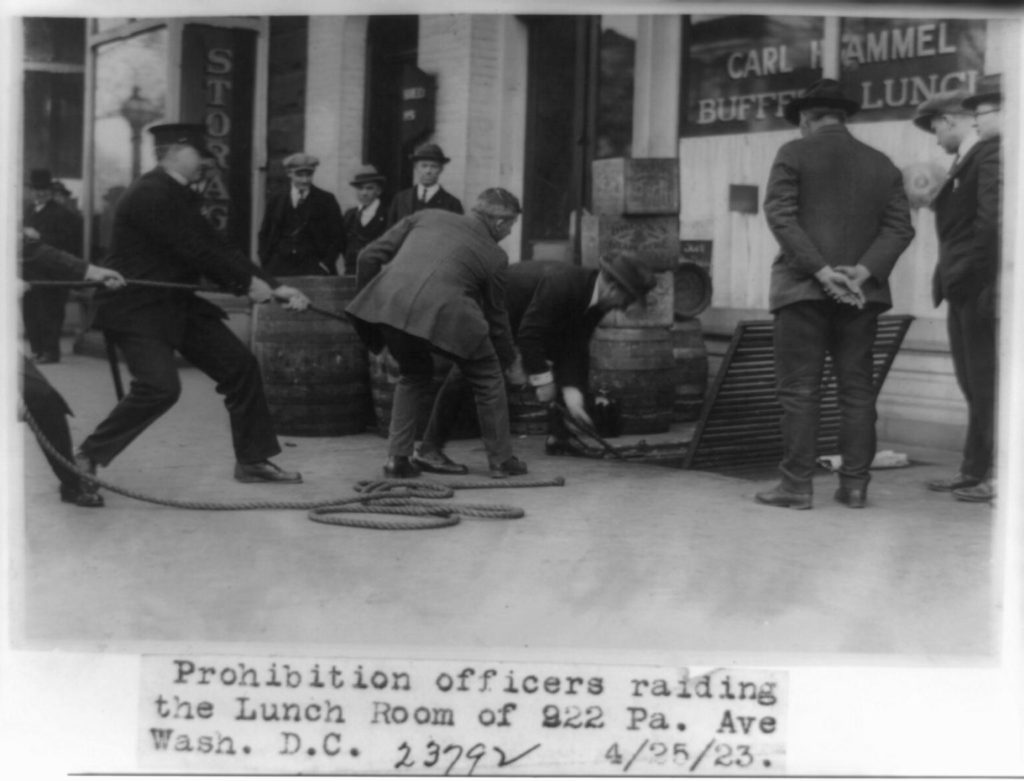

From 1920 to 1933, the Eighteenth Amendment of the United States constitution banned alcohol. The Eighteen Amendment, also known as Prohibition, has the honor of being the only constitutional amendment to be repealed with another constitutional amendment.

Although prohibiting alcohol is now seen as absolutely ridiculous, hindsight is 20/20 and Prohibition began with noble intentions. According to the Cato Institute, it was “undertaken to reduce crime and corruption, solve social problems, reduce the tax burden created by prisons and poorhouses, and improve health and hygiene in America.”

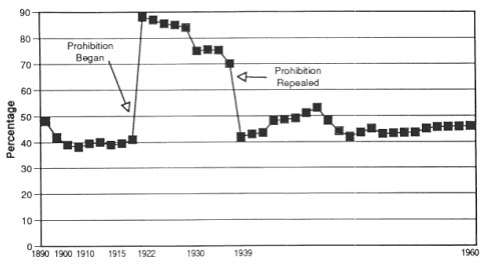

Source: Clark Warburton, The Economic Result of Prohibition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), pp. 114-15; and Licensed Beverage Industry, Facts about the Licensed Beverage Industry (New York: LBI, 1961), pp. 54-55.

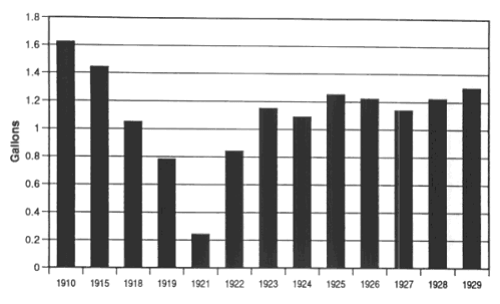

Needless to say, that did not come to pass. Alcohol consumption dipped initially, it increased soon after, and led to the organization of crime. Demand continued, the legality of supply be damned. Prior to Prohibition, crime bosses such as Al Capone were relatively small-time menaces. The “noble experiment” made illegal alcohol a lush business opportunity. It also led to networking opportunities for these mafiosos, as the sourcing and distribution of alcohol often requiring crossing state lines.

“Mobsters couldn’t work in isolation if they wanted to keep the liquor flowing and maximize profits,” said Dave Roos, a freelance journalist in History.

Source: Clark Warburton, The Economic Results of Prohibition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), pp. 23-26, 72.

A 2010 Congressional Research Service study found that organized crime in capable of weakening the economy with illegal activities because they can cause state and federal governments to lose tax revenue. Prohibition cost the United States government $11 billion in tax revenue. According to PBS, a long-term consequence of this was that multiple state governments, in addition to the federal government, would on income tax revenue to fund their budgets.

Enforcing Prohibition also turned out to be a costly endeavor. In 1921, Prohibition enforcement began at $6.3 million. By 1930, it cost $13.4 million to enforce.

During Prohibition, kingpins could make as much as $1.4 billion in 2018 currency.

Meanwhile, other industries that were expected to rise as a result of Prohibition actually ended up struggling. Top industries with expected growth were clothing, chewing gum, grape juice, soft drink and theatre producers. Essentially, every non-booze industry that could provide a new way to entertain Americans expected an increase. According to PBS, theatre revenues declined and restaurants failed to turn a profit without legal liquor sales.

PBS found that “the closing of breweries, distillaries, and saloons led to the elimination of thousands of jobs, and in turn thousands more jobs were eliminated for barrel makers, truckers, waiters, and other related trades.

The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 ended gangster’s profitable bootlegging enterprises, and many returned to classic criminal operations like gambling and prostitution. The Great Depression, like Prohibition before it, provided mobsters with a golden opportunity: loan sharking.

Unlike many Americans during the Great Depression, the gangs had cash in an economy that wanted in. Like with alcohol, the people had the demand and the gangsters had the supply.

According to Howard Abadinsky, a criminal justice professor at St. John’s University, it became clear to many that if people wanted to do something that required cash, they needed to get in cahoots with the likes of Al Capone, Bugsy Segal and “Lucky” Luciano. The law of the land was irrelevant in many ways, and money-laundering techniques were extremely powerful.

“If you wanted to set up a legitimate business, [you] have to go to organized crime. Loan Sharking becomes a major industry,” Abadinsky said.

Sources:

- https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/alcohol-prohibition-was-failure

- https://www.history.com/author/dave-roos

- https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40525.pdf

- https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/unintended-consequences/

- http://digitalexhibits.wsulibs.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/prohibition-in-the-u-s/negative-economic-impacts-of-p

- https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/crime-in-the-great-depression