The year was 1998. The Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (ESPN) was trying to close a landmark deal with the National Football League. The goal was to finally bring the crown jewel of sports content, professional football, over to ESPN for weekly primetime scheduling. To close this deal, ESPN had to ask its parent company, Disney, and their CEO Michael Eisner for permission to pay the NFL’s exorbitant rights fee. Eisner agreed, on one condition: ESPN would have to divert the cost to cable companies in the form of annually increasing subscription fees. The head of sales, George Bodenheimer who would later become the longest tenured President in company history, had to do the impossible.

Bodenheimer had to convince various cable affiliates to a new seven-year deal with a compounded 20% annual increase in subscription fees. By the stroke of unparalleled salesmanship, and a fair amount of luck, Bodenheimer secured the agreement from the major cable players across the country. Thus, ESPN, only nineteen years old at the time, finally had professional football in primetime. They would soon discover that the landmark seven-year deal, and not football, was the true jet fuel for ESPN’s meteoric rise in revenue and spending power.

This seminal moment in ESPN’s ascent to supremacy in the world of sports television is recounted in deep detail in James Andrew Miller’s oral history of the company, “Those Guys Have All the Fun.” In the book, Miller quotes Hearst CEO Vic Ganzi who estimated “that single stroke of genius sent ESPN’s carriage fees from 40 cents to $3.20.”

The deal reverberated around the entire cable ecosystem because of its shocking potential. To put the deal into perspective, achieving a 20% return annually over seven years would yield a return of 358%. This growth in revenue was so tantalizing and surprising that even Eisner didn’t believe it was possible. Bodenheimer recounts in his memoir the task of relaying the news to his boss. ‘“Impossible!” said Eisner. “Nobody will pay that.”’ Yet they did, and ESPN reaped the rewards.

One of ESPN’s most popular shows with its longtime host Chris Berman

This deal speaks to ESPN’s true competitive advantage as a network. ESPN has the highest subscription fee of any cable network, which is how much cable and satellite TV providers charge per month to users for access to the channel. This tremendous influx of cash flow allows ESPN to outbid other networks with lower subscription fees that are more reliant on advertising as a form of revenue. ESPN also can command exceptionally high advertising rates because they reach the adult male demographic, a prized catch among advertisers.

This potent dual revenue stream is what positioned ESPN as the market leader for rights deals over the last twenty years. As they became the place to find any sort of sporting event, their ratings and popularity exploded further, and their fees and advertising rates climbed even higher. It seemed nothing could stop this blockbuster business in the first decade of the 21st century. However, recently ESPN has found itself in a business quagmire of epic proportions.

The reason: the technological disruption of the cable industry. Over the last five years, television has been turned on its head. The way individuals consume media has shifted dramatically, and spending preferences have followed accordingly. With options like Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu the new generation of content consumers have more mediums to choose from than ever before. Additionally, DVR and Tivo, mechanisms to record shows, have rendered live television obsolete for the most part. Thus, “cord cutters” can pick and choose their favorite shows and avoid cable altogether.

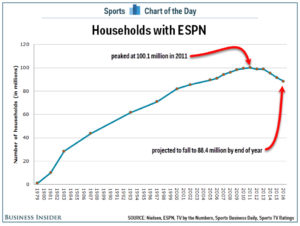

For those loyalists who want a basic cable package, there is now the “skinny bundle,” a slim selection of channels that provides the necessities. Six months from now there will probably be even more options. In turn, ESPN’s revenue from subscriber fees has declined precipitously and it appears that trend is not stopping anytime soon.

According to Business Insider Intelligence, in October of 2016 ESPN “lost 621,000 cable subscribers, the most it has ever lost in a single month.” While that number, provided by Nielsen, has been disputed inside the kingdom of ESPN, the fact remains that the company is contracting. According to Nielsen estimates, ESPN has dropped below 89 million subscribers for the first time in a decade. Even more alarming is the fact that the company will lose close to three million subscribers in this calendar year alone. 60% of ESPN’s revenue comes from subscriber fees alone.

The dominance of ESPN has always been its robust dual revenue stream. As of now, just ESPN, without the other companion networks like ESPN 2 and ESPNU, commands a staggering $7.04 monthly subscription fee. Losing three million paying customers over the course of the year translates to a decrease in revenue of close to 250 million dollars annually. In the world of ESPN, where double digit growth is the norm, stagnation is unacceptable. One can only imagine what contraction means for the company.

Some experts and executives in the media industry think that ESPN creating a standalone service similar to HBO NOW is the magic antidote to all of their problems. The issue with this is that unlike content on HBO that is watchable at any time, the market has not shown a propensity to watch delayed live sports events. While it is perfectly acceptable and enjoyable to watch Game of Thrones a week late, the same cannot be said of watching a week old showdown between the Lakers and the Thunder. Additionally, this would violate current contracts on their deals and there is no incentive for individual professional leagues to use ESPN as their middleman when they can air direct to consumer.

Even more than that issue is the fact that to match ESPN’s current revenue with the standalone model, the company would need to charge an exorbitant rate per user of the service. The reason the cable model is failing is precisely why ESPN is succeeding. Millions of cable subscribers pay ESPN’s monthly fee without ever turning on the channel. With the new consumer driven economy, this inefficiency is slowly evaporating, and ESPN’s bottom line is feeling the brunt of that damage.

To compound this problem, ESPN is losing a lot of its signature talent while facing stiff competition as well as stagnant ratings on its two marquee programs: Monday Night Football and Sportscenter.

Over the last two years, ESPN has lost its most popular columnist, one of its most prominent radio hosts, and the most polarizing and talked about morning sports show TV host. The three: Bill Simmons, Colin Cowherd, and Skip Bayless all left because of friction with management and for more money. Fox Sports 1, the well-funded and fairly new competitor, flexed its financial might to pick up both Bayless and Cowherd. While Fox may have overpaid, the signings and other marquee additions like Erin Andrews, have put the TV network on the map. These were the types of moves ESPN would make in the past. As a result of its growing popularity, and a historic Chicago Cubs playoff run, Fox Sports 1 actually topped ESPN in ratings over the course of the October 13th to October 20th week for the first time since FS1 launched in August of 2013.

An FS1 show taking market share away from ESPN

The ratings drop affects ESPN’s other revenue driver: advertising. Since the advent of ESPN, the reason it has always commanded such high rates is because of its hard to reach demographic. For years, adult men have been the white whale and ESPN has been the bait to lure them in. Unfortunately for the company, ratings are down. Sportscenter, which rose to prominence in the 1990’s with transcendent hosts Keith Olbermann and Dan Patrick, has seen its ratings decline 27% since 2010. According to Sports Business Daily, the coveted 18-34 year old demographic has been hit even harder, with a 36% drop.

The two most popular hosts ever

The reasons for this are twofold. First, Sportscenter has failed to groom and create on air personalities that drive viewers the way Olbermann, Patrick, and many others did in the past. Second, highlights are now ubiquitous. One can access every highlight they want from the palm of one’s hand, without turning on Sportscenter. In a sense, the utility of the show is now obsolete. The only reason to tune in is because of the on air talent as well as the packaging. The company has tried to fix this problem by bringing in well liked Scott Van Pelt to host his own hour. This has created a brief resurgence, but there is a problem that still remains.

The new era with Scott Van Pelt

Sportscenter was the wagon that ESPN hitched itself it prior to signing the NFL. It is central to the ESPN ethos, and it represents more than just sagging ratings. In a way, Sportscenter has to work for ESPN to succeed. USC professor and sports media consultant Jeff Fellenzer says that “Sportscenter is so central to the ESPN brand and what they do that the company has to figure out some way to make it work.”

In addition to Sportscenter, Monday Night Football has also been an issue for the company. When ESPN inked the deal for the crown jewel of sports programming last decade, it unfortunately got stuck with the “B” schedule of games. The NFL moved their highest quality games to Sunday Night Football on NBC, and gave ESPN the former Sunday Night schedule. This dramatically diminished the quality of games on Monday night, and has led to less than primetime matchups. In turn, fewer people have tuned in. Since ESPN pays close to two billion dollars a year for Monday Night Football, in addition to the right to broadcast NFL highlights all week, losing viewers is not an optimal situation for the network.

This decrease in revenue puts the network in a precarious position, with rights deals for sports programming growing more expensive each round. According to Business Insider, ESPN literally will not be able to afford their league contracts if the number of subscribers continues to decrease.

The capital markets have taken notice. ESPN, which was valued by Forbes at 40 billion dollars, only a few years ago, has dragged down the price of Disney’s stock almost single handedly over the last year. In their last earnings report, Disney missed significantly on revenue numbers because of ESPN’s shortcomings.

Overall investors and spectators are concerned about ESPN’s future, and they wonder if the company can somehow find a new deal that rivals the earning potential of Bodenheimer’s signature achievement. Whether that is feasible remains to be seen. What is clear however is ESPN’s need to innovate in some capacity, to avoid the fate of fallen media giants before them.

The company has an array of options to choose from, and the strategy they take moving forward will be interesting. In terms of rights deals, the company can collaborate with other companies to split the monumental asking price of the various leagues. They have done this already, working with Fox on a deal for the PAC 12 and there will be more of these to come in the future. Fellenzer believes this is an absolute necessity as they won’t be able to afford as many rights deals on their own. “You will definitely start to see more of the PAC 12 deal type collaborations, I think it is the way to structure it moving forward,” Fellenzer said.

On the subscription front, the company may be able to work out deals with individual providers and other streaming services. They have started this process, offering ESPN on sling TV, a skinny bundle provider.

At the end of the day, the company is undoubtedly at a crossroads. However, they have the benefit of practically every league deal for the next decade. Live sports is still the one holdout for the rapidly shifting media landscape, and ESPN can use this decade of practically guaranteed viewers to innovate and figure out its next landmark move for the future. The company has been skilled enough to build one of the biggest media brands ever, so betting against them moving forward should be done with caution. There is a reason they are the worldwide leader in sports.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.