Part One: The Student Debt Crisis and How We Got Here

Pursuing a degree in higher education is often romanticized. The mentality has remained that a job is guaranteed as long as you sacrifice anything and everything for a bachelor’s degree, and ideally, a master’s degree or two. Of course, there are valid arguments for this, and for the most part, it’s true. Over time, all the financial strife will be well worth the wait, as education is an investment into the future.

But what happens when the investment doesn’t pay off? It is not uncommon for students to have a period of unemployment post-graduation, which results in ignoring those looming student loans. In addition to this, we all know the job market is still on shaky ground, and not all of us will find something that actually pays us enough to survive.

According to Student Loan Hero, the total U.S. student loan debt is up to $1.2 trillion, with 40 million borrowers, and $29,000 being the average balance. Why have we allowed this to become our reality? Despite a generous financial aid package, even I fit into this statistic. To sleep at night, I let myself believe, “You’re in USC Annenberg, and you’ll be fine.”

Unfortunately, this is the mentality many students have. A respected degree from a prestigious university helps, but nothing is guaranteed. Student loan debt is often blamed on private universities, but cuts in state budgets have led to a rise in tuition at public universities as well. Additionally, private universities sometimes have more scholarships than public universities can afford to offer. It is difficult to argue that private establishments are not the worst offender, because of course they are. However, it is a case-by-case basis (for example, the UC’s had little to no scholarships available to me, therefore I would have a similar debt situation graduating from UCLA.)

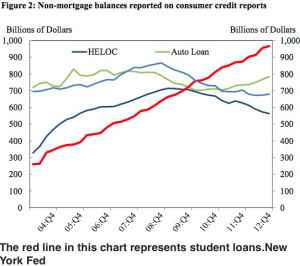

At the end of the day, it is better to have a degree, but the federal government’s over eagerness to give out student loans has led to a serious problem. According to Business Insider, Bill Ackman is convinced the outstanding balance in student debt could trigger the next market crash. Ackman claims that the government has loaned out too much money, which is true. “Student-loan delinquencies, in red, have risen as late payments in other types of payments have dropped,” according to a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The student loan debt crisis is being compared to the housing market crash. Wall Street kept saying “the housing market is stable, there’s nothing to worry about.” Throwback to 2008 when our country faced the worst recession since the Great Depression. Ringing any bells? We all know history repeats itself, so why is it so hard to connect the dots, and realize predatory lending back then, isn’t so different from our current situation?

To clarify, it is a tad exaggerated to say the student loan debt crisis is a carbon copy of the housing market bubble. However, the issue is the casual attitude towards loans, credit cards, and OPM in general. Since the 1970’s, the convenience of credit cards and the mentality of “get it now, pay later” has transformed our economy. This transformation was crucial since consumers were encouraged to spend, which drove the demand up, which all in all boosted the economy. Today, without credit cards and the ability to borrow money, our economy would be at a stand still. Nonetheless, student loans are another story. Especially when student loan knowledge is lacking. According to a survey by intuition, two-thirds of millennials who received loans felt they did not have enough information about their loans. 45% of students are not receiving repayment counseling, 47% do not know the interest rates on their loans, and 75% have not been offered an income-driven repayment plan. In summary, college students do not know what the heck is going on. It is easy to point the finger at the students. Obviously, we don’t care about our financial future if the tiny, fine print isn’t read word for word right? Wrong! Student loans are perceived to be far more confusing than they actually are, the repayment process feels much more difficult than necessary. We all know young people are a bit naive, so why would the government or private lenders willingly keep us dazed and confused? It’s like they want us to default.

Additionally, no one is doing us any favors by never capping the amount of money we can borrow. There are measures taken to ensure that students don’t take advantage, but there are too many loopholes. Students are usually given a six-month grace period post graduation. What happens when graduate school is the next step? Paying back undergraduate loans are deferred, the interest goes up, and a few years later, you may be looking at paying off loans for 30 plus years. In some cases, the rest of your life.

Take Liz Kelley, an extreme example of how allowing students to borrow to their heart’s desire is risky business. In the New York Times article “Student Debt in America: Lend With a Smile, Collect With a Fist,” Ms. Kelley admits that she “made her own choices.” Ms. Kelley has $410,000 in debt due to a number of circumstances. Long story short, Ms. Kelley had financial factors such as her autoimmune disease, childcare, divorce, foreclosure, and much more that kept delaying her from completing her education. By the time she finished undergraduate school and eventually graduate school, the interest rates destroyed her ability to pay all this back anytime soon. This story goes to show the “deep contradictions in the federal governments approach to student loans.” There are so many students that are still handed out loans, despite a shaky history of repaying loans in the past. When it is time to pay back the loans, forgiveness is hard to come buy. This is setting students up for failure, and most importantly, the decline of our economy.

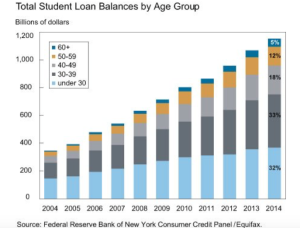

The argument is made that those with the most debt have the highest degree, and therefore have the means to pay back loans. In many instances, this holds true. However, according to William Elliot, director of the School of Social Welfare at the University of Kansas, ” ‘even people with only $5,000 to 10,000 [in loan] are still going delinquent.’ ” The Federal Reserve study reveals that the 90-day student delinquency rate has raised to 11.3%. The White House Study attributes this to drop outs or people with lower degrees (who therefore have low wage jobs,) but that doesn’t mean delinquency only applies to a certain group of people. The fact of the matter is delinquency is rising, and the amount of student debt people under the age of 35 must pay back is decreasing economic growth due to lack of willingness to spend.

Part Two: How Student Loan Debt is (Potentially) Crippling the Economy

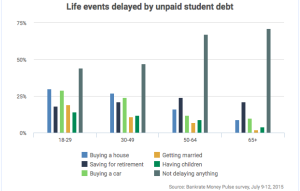

Millennials are the future of the economy, and yet most are reluctant to be ” ‘big spenders’ .” According to the Los Angeles Times, millennial’s are cautious as ” ‘children of the Great Recession.’ ” However, there is much more complexity to this issue than millennials simply being too frugal (in comparison to past generations.) Student debt is a major deterrent from investing in the future. The graph below (left) shows how people aged 35 and under have much higher student debt rates than past generations. Therefore, buying a house, marriage, child rearing, even buying a car is all postponed. Many students resort to living with their parents, not because millennials are too “coddled” (I promise you no one willingly lives with their parents post grad,) but because ” ‘student loan debt, more than any other kind, contributes to people having less favorable views on their own financial well-being.‘ ”

The lack of confidence in spending has lead to the slowing of our GDP and overall economic growth. As young people put off buying homes, the housing market slows down. Those who need to sell their homes are unable to, because the young, hip couples are crammed in their minuscule, overpriced apartment. According to a survey conducted by the National Association of Realtors and American Student Assistance, “seventy-one percent of those surveyed said their student loan debt is delaying them from buying a home. More than half said they expect that delay to last longer than five years. ” Additionally, one third of current homeowners revealed that they cannot afford to sell their home and buy another one because of student debt. Something else to keep in mind is that not being able to pay back student debt negatively effects your credit score, and your credit score effects every crucial financial decision in life, such as buying a home. This is probably another reason why the housing market has struggled recently.

(Note: As of May 2016, there was indeed a boost in the housing market. However, this survey was taken in June 2016 and indicates that the housing market is still not as strong as it should be. Everything else in the economy? Sluggish in comparison.)

Waiting to have children till later in life is not the end of the world, but if this continues for too long, our economic future could adversely affected by not having enough young people in the next generation (take Japan or Germany as great examples.) Not saving for retirement could also cause problems down the road. All in all, everything is being affected by student debt, more than economists and the elitist Wall Street “geniuses” would like to admit

Wall Street believes that student debt is a ” ‘fiscal headache rather than a financial risk,’ “ since many loans are backed up by the federal government. Most are convinced that due to this, there is a low chance of another financial crisis if defaults become rampant. However, if the government ends up needing to bailout student loan debt, the $1.2 trillion necessary to do so will halt economic growth, and raise taxes.

The hesitance to refer to the student loan debt issue as “crisis” is the wrong action to take. Why wait for things to get worse when there are ways to fix the problem now? Senator Elizabeth Warren and Attorney General Kamala Harris have made the effort to find solutions, but no one has taken them seriously. Decreasing government loans is not the right move either, as the demand for student loans would stay the same, and private lenders would swoop in and take further advantage of students. Some might say blaming student loan debt for the slow economic growth is pushing it, but why discredit the statistics that are right in front of us? Why ignore the millennials, who are arguably the most important group of people for the future of the economy? It is only a matter of time before this problem thoroughly unravels, and all we will be able to do is say, “I told you so.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.