When I first came to the United States with a student visa eight years ago, I dreamed of working in the states because my friends and family members had been talking to me about how America is the land of opportunity. Yet, it is very interesting for Koreans to view how the United States has more opportunities than Korea because South Korea has had lower unemployment rate than the United States has had by having the unemployment rate of 3.2% in 2008.

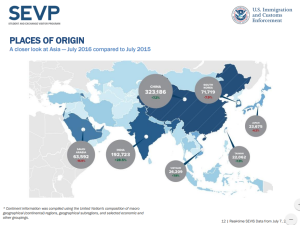

Just looking at data on 2005, South Korea was ranked as the number one country to have the largest population of students studying abroad in the states. According to an article in Radio Korea in 2006, the U.S. had 117,755 Korean international students. Furthermore, the article states how most of South Koreans wanted to live and work in America between 2005 to 2006. This sentiment indicates how many Koreans (either students or workers) regarded the United States as the economic powerhouse where it was very desirable to leave their homes.

Though South Korean youths dreamed about immigrating to the United States, there was a problem. For countries with low birth rates, it is advantageous to attract intelligent and talented foreigners to expedite countries’ development. In case of South Korea, the foreign workforce in the country has been concentrated in manual labor, which does not require high education background. Does the allocation of foreign workers in manual labor mean that South Korea has a high birth rate? No, the World Bank Statistics in 2014 indicates that South Korea has suffered from low birth rate of 1.21 children born per women.

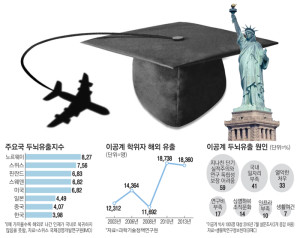

With low birth rate and less welcoming of educated workers, South Korea should have a great education to promote R&D. However, there is an indication where the intelligent and talented Koreans are avoiding to work in their homeland when they are getting PhD through studying abroad. According to the Korean Institute for International Trade report on 2006, South Korea had brain drain of 1.4% from 1990 to 2000 and it has not been getting better at all.

Why would the students be hesitant to go back to their country? Is it economically bad to go back to Korea? To answer this, it is important to compare Korean economic history between 1990s and today because the change in economy and social consciousness may be the reason for the brain drain.

Until the Asian financial crisis in 2007, South Korea was having the prime time of its economic prosper. According to the article Finance and Growth of Korean Economy from 1960 to 2004 in Seoul Journal of Economics by Shin-Haing Kim, the political shift from military despotism to democracy made better environment for Korean economy to grow. The democratization of politics in 1987 fostered economic liberalization and brought higher wages. In 1996, South Korea became the member of OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) by meeting the requirement of having enough income per capita.

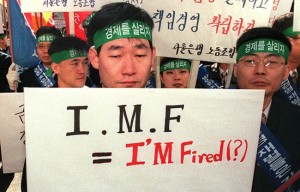

Despite the increase in wages ensured Koreans to have high hopes for further economic growth, Chaebol econom y ultimately triggered South Korea to fall into Asian financial crisis of 1997. Chaebol (재벌) is a unique economic faction in Korea that is equivalent to family owned conglomerate. In the 90s, the government favored Chaebols and started to implicitly guarantee loans for them. In the essence, the government guided the fund allocations towards Chaebols by favoring them; the process of non-biased surveillance and evaluation of risks was skipped. Where the loans should have been granted equally to small business owners and firms, the loans were concentrated to Chaebols. In turn, the Chaebols became too big for the government to bailout when they were in debt. Consecutively, the foreign investors lost confidence in the ability of Korean economy to protect loans and many loans were withdrawn. As a result, big Chaebol corporations such as Hanbo, Sammi, Jinro, and Kia defaulted and the government had no power to bail them out. With the Chaebols fallen, South Korea faced a great amount of debt and South Korean government reached out to International Monetary Fund for financial remediation.

y ultimately triggered South Korea to fall into Asian financial crisis of 1997. Chaebol (재벌) is a unique economic faction in Korea that is equivalent to family owned conglomerate. In the 90s, the government favored Chaebols and started to implicitly guarantee loans for them. In the essence, the government guided the fund allocations towards Chaebols by favoring them; the process of non-biased surveillance and evaluation of risks was skipped. Where the loans should have been granted equally to small business owners and firms, the loans were concentrated to Chaebols. In turn, the Chaebols became too big for the government to bailout when they were in debt. Consecutively, the foreign investors lost confidence in the ability of Korean economy to protect loans and many loans were withdrawn. As a result, big Chaebol corporations such as Hanbo, Sammi, Jinro, and Kia defaulted and the government had no power to bail them out. With the Chaebols fallen, South Korea faced a great amount of debt and South Korean government reached out to International Monetary Fund for financial remediation.

In 1998, South Korea had a record low GDP growth rate of -7% and it seemed that all hope was lost. However, Korean people rose up together and voluntarily accumulated 227t of gold to recover from financial crisis. According to an article in Korea Daily, the Koreans at the time submitted their luxury assets like gold bracelet and wedding rings to support their homeland to get out of the crisis. Though this campaign was not the main source of Koreans to escape from crisis, South Korea was able to pay the debt and interests to IMF one year earlier than it was expected to.

Entering 2000s with free of IMF debts, South Korea has emerged as one of strongest Asian economic hubs alongside of China and Japan. From 1998 to 1999, the GDP growth had a miraculous increase from -5.7% to 10.73% according to data listed on The World Bank. From 2000 to 2015, South Korea’s GDP growth in 2000s is recorded to be 4.25% in average, which is bigger than the average United States’ GDP growth in 2000s (1.929%). Though the export heavy economy of South Korea has been showing slow growth, the unemployment rate has been low as 3.5% in 2016. However, the surviving Chaebols still assume a great power in economy and politics in Korea.

Economy definitely has gotten better for South Korea. However, the students who received doctorate degrees overseas state that they prefer staying outside Korea due to the disadvantageous circumstance they face as they get back. Mostly, the brain drain (phenomenon of talents emigrating into other countries) in South Korea is shown by the engineering and science talents migrating into the United States. According to Meil Business Newspaper’s analysis from the 2016 report of American National Science Foundation, 65.1% of Korean international students with doctorate degrees in engineering and science favored to stay in the states. MBN also interviewed one of the international students who recently received a doctorate degree in engineering from Stanford. He said, “If I return to Korea, I may have to say permanent good-bye to my family. There are no universities offer me to be a professor and the jobs offered by corporate labs are all far away from the main city. I rather try to get a job at the U.S. defense company so I may get a citizenship. I know I may face racism, but I think being a second citizen is better than having no place in Korea”.

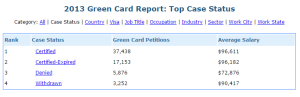

According to Radio Korea, international students with doctorate degrees in engineering/science leaving South Korea has increased from 2006 to 2016 by 170%. Yet, staying in the United States can often pose more problems for the Korean talents. In order to work in the U.S., the international graduates need to apply for jobs that sponsor working visas, and it is not an easy task. According to myvisajobs.com, the rate of U.S. companies granting visa sponsorship to foreigners in 2013 was roughly 55%. In other words, only the half of total international graduates may work in the states legally. In addition, obtaining employment as a foreigner in the U.S. is a very painstaking process. First, the foreigner needs Permanent Labor Certification(ETA Form 9089). Then the foreigner needs an Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker(Form I-140). And finally, the foreigner needs an Adjust of Status to a permanent resident of the United States(Form I485). It is definitely not an easy process to go through.

In order to work in the U.S., the international graduates need to apply for jobs that sponsor working visas, and it is not an easy task. According to myvisajobs.com, the rate of U.S. companies granting visa sponsorship to foreigners in 2013 was roughly 55%. In other words, only the half of total international graduates may work in the states legally. In addition, obtaining employment as a foreigner in the U.S. is a very painstaking process. First, the foreigner needs Permanent Labor Certification(ETA Form 9089). Then the foreigner needs an Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker(Form I-140). And finally, the foreigner needs an Adjust of Status to a permanent resident of the United States(Form I485). It is definitely not an easy process to go through.

Despite this not-so-favorable employment condition in the United States, the South Korean engineering/science talents desire to stay in the U.S. after getting doctorate degrees because the Korean academia does not socially welcome them . As stated in the interview above, becoming a professor in Seoul is extremely difficult for Korean international graduates. To begin with, the Korean work space culture often repel the international graduates. According to the book The Korean Mind by De Mente and Boye Lafayette, Korean workers inside Korea value the concept of “Anshim” or 안심. Mente and Lafayette describe “Anshim” as a “peaceful heart” state of mind that is developed from Buddhism and Confucianism. Though this concept is about finding peace in mundane, it also reflects how close-minded the Korean people are. Mente and Lafayette further comments on this state of mind in their book that “Anshim” dictates Korean language, etiquette, ethics, personal relations, and even business relations. For “Anshim” state of mind, irregularity is a very negative force. For the case of talents returning with doctorate degrees overseas, those talents are the irregular force that will invade the safe space of academia to the professors in Korean universities; the degree earners come back with American demeanor and suggest ideas that are not common in Korean academia. In turn, the Korean professors will outcast the foreign doctorate degree earners; this creates the similar discrimination as racism in the United States.

Furthermore, becoming a researcher in Korea is not profitable to the U.S. graduates due to poor wages. For example, the U.S. offers $80,000~$90,000 as the first annual income but Korea offers about $35,707 (converted from 40,000,000 Korean Won). For the less wages and cultural discrimination, Radio Korea criticizes Korea for not providing solution to these returning doctorate degree earners.

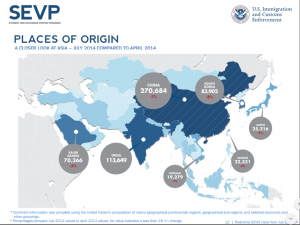

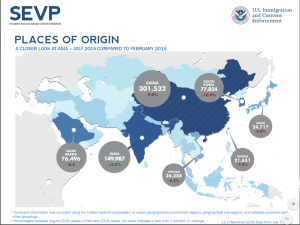

Interestingly, the amount of Korean international students in the U.S. has decreased over the years, contrary to the concern of the brain drain and falling demand in international students’ willingness to return to Korea. I compared the statistics of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement report on 2014 and 2016. Between those years, the percentage of Korean students studying abroad in the U.S. drops year by year. The Financial News (Korean news agency) also has reported that the amount of U.S. dollars Koreans spent on studying abroad in the U.S. decreased from $1,920,000,000 on 2013 to 1,570,000,000, which is 18.1% decrease over the three-years period. According to its statistics, the Korean international students fell by 20% from 2011 (262,465) to 2015 (214,595) because there are no longer additional merits the international degrees offer to students who strive to get jobs in Korea. According to the Korean Ministry of Employment and Labor, the labor market is not favorable to the student population. In 2013, the ministry stated on an article in Ulsan Daily that the total unemployment rate was 4% but the youth unemployment rate (15 to 29 years old) was 9.1%. The ministry sees the rate of achieving higher education as the problem. By 2011, 72.5% of youth work force had university degrees; thus, the youth work force became overqualified for most of jobs offered. This was the same for the returning studying abroad students as well. Since there has been an increasing trend of students who studied abroad from 2006 to 2011, the international degrees lost its values; the supply increased but demand fell down.

Besides the increasing supply of international degrees losing its value, the United States’ sentiment on foreign workers affect the decrease in value of degrees outside Korea. According to the interview Dong-A Daily (Korean News Outlet) had with a Korean employer in the states, he said: “The U.S. government demanded answers for my decision to hire a Korean international student. They came to the office very frequently to find any wrongdoing of my company just because I hired non-U.S. citizen.” According to Dong-A, there are similar cases in which the employers made a policy within the company to only hire U.S. citizens because they want to avoid any trouble. This sentiment is also clearly shown in this presidential election. The policies regarding international students have been tweeted and stated by both candidates.

As introduced in Little Book of Economics by Greg Ip, ideas, population, and capital are crucial for economic growth. On this issue of global talents immigrating and emigrating, ideas and population are directly influenced by those talents. As mentioned above, it is a great strategy for developed country with low birth rate to welcome more global talents and acquire jobs to make up for the low birth rate and further innovation. Yet, a recent phenomenon of global talents returning to their native countries after acquiring degrees and doctrine makes Korean problem bizarre. According to an article in the Huffington Post, the “People born in developing countries move to well-developed ones . . . but with the passing of time, some of them are willing to go back to their native country ‘to breed in the area where they were born'”. Just as Huffington Post describes with many international students from China, Kenya, and Italy, Korean students should also feel more confident to use the knowledge they have acquired from the U.S. universities in their own native countries.

The highly intelligent Korean international students not returning to their homeland can be damaging to Korean economy because the innovation may slow down.  In any market competition, research and development are very crucial. Yet, the phenomenon of South Korean students who have potential to advance the R&D in their homeland getting discouraged by the work environment is definitely an issue Korea needs to solve in the future. The prime reason for the bad environment is the Korean university boards. According to the Hanguk-Kyungjae (Korean economics newspaper), Korean universities lack interdisciplinary system. Even though the Korean board of education publicly promoted interdisciplinary education, the professors in academia thought otherwise. The article describes that the professors think if professor A in one field of study tries to fuse his or her field of study with professor B’s field of study, they think of this phenomenon as an invasion instead of innovation. This view clearly has to do with aforementioned Korean state of mind, “anshim”. Due to the fact that “anshim” culture makes the academia to be very close minded, interdisciplinary education only exists as a noun. This problem is what repels the foreign doctorate degree earners as well. The students who earned their doctorate degrees in the United States are very used to interdisciplinary studies that they may want to research further when they become professors in Korea. However, the cultural state of mind hinders their motivation to come back and contribute to the close-minded academia.

In any market competition, research and development are very crucial. Yet, the phenomenon of South Korean students who have potential to advance the R&D in their homeland getting discouraged by the work environment is definitely an issue Korea needs to solve in the future. The prime reason for the bad environment is the Korean university boards. According to the Hanguk-Kyungjae (Korean economics newspaper), Korean universities lack interdisciplinary system. Even though the Korean board of education publicly promoted interdisciplinary education, the professors in academia thought otherwise. The article describes that the professors think if professor A in one field of study tries to fuse his or her field of study with professor B’s field of study, they think of this phenomenon as an invasion instead of innovation. This view clearly has to do with aforementioned Korean state of mind, “anshim”. Due to the fact that “anshim” culture makes the academia to be very close minded, interdisciplinary education only exists as a noun. This problem is what repels the foreign doctorate degree earners as well. The students who earned their doctorate degrees in the United States are very used to interdisciplinary studies that they may want to research further when they become professors in Korea. However, the cultural state of mind hinders their motivation to come back and contribute to the close-minded academia.

The Hanguk-Kyungjae further sees this exclusivity problem in Korean academia as the main factor of not-returning intellectual talents who have acquired degrees overseas. Although South Korea has experienced tremendous of economic prosperity ever since the end of the Cold War due to innovative technologies in electronics and automobiles, the experts see that innovation is slowed down because of the exclusive culture in academia and it will slow economic growth even further. Though the number of Korean international students are declining, the brain drain issue is critical in South Korea because it will eventually slow down the competitiveness of Korean products. Though those are my worries, the future is still unknown because of the youths in Korea. Every year, the youth population are moving in the direction of becoming more open-minded than the generation before them. If Koreans continue to try, the struggle for returning foreign degree earners might meet its end. Culturally, Korea has definitely become more progressive compare to its very conservative past. Just as it is a remedy for everything, time may be the answer for the perception Korean academia has on foreign degree earners; thus, the problem of brain drain may be over in the future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.