A nomadic herder rides past a traditional ger in Northern Mongolia.

Traveling outside of Mongolia’s only major city, Ulaanbaatar, can seem like traveling back in time 800 years. Among the hundreds of miles of rolling hills in which you would be hard pressed to find any permanent, man-made structure, you half expect to see Genghis Khan’s enormous army thunder down a hill aboard hardy little ponies. Nomadic herding culture has been a part of Mongolia for thousands of years and it remains a major part of Mongolian life however, Mongolia’s economy is undergoing massive transformation that could change both the cultural and natural landscape forever.

From 2009 to 2013, the Mongolian GDP nearly tripled in size from a scant $4.584 billion (US) to $12.582 billion, according to the World Bank. Yet more important than the rise of the nation’s GDP is the source of economic growth and geographic location: valuable minerals and metals and its location just north of resource hungry manufacturing powerhouse, China.

The story of Mongolia’s rise from irrelevance to noticeable actor in the Asian sphere began in 1997 when the democratic government, established after the fall of the Soviet Union, which maintained Mongolia as a buffer against China, passed the Minerals Law of Mongolia. This law established the state’s ownership of all mineral resources within its borders and reserved the right to sell mining and exploration licenses.

The goal of this law was to grow Mongolia’s economy after a dip that left their GDP below the billion-dollar mark from 1993 to 1994. If the government could sell its mining and mineral exploration rights to international mining corporations, it could dramatically increase levels of foreign direct investment, lower unemployment, and raise GDP.

For investors, abundant Mongolian reserves of copper, gold, fluorspar, and uranium were highly attractive. Especially in the early 2000s when prices for rare earth metals and minerals were climbing. In addition to natural resources, Mongolia shares a border with China, the world’s largest importer of raw materials. This presents a lucrative opportunity to sell materials to China at a lower price by minimizing transportation costs that make metals and minerals from South America more expensive.

Combining natural resources with its proximity to China, a country that imported $25.1 billion in refined copper and $63.9 billion in gold in 2014, Mongolia looked like the world’s premier destination for mining operations.

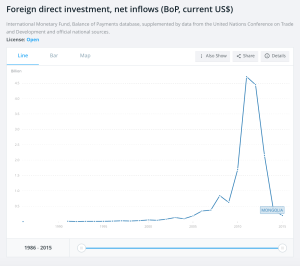

After a few years of exploration on the Mongolian steppes, international mining mavens concluded that there were fortunes to be made and the investments started pouring in. From 2009 to 2011, a World Bank report found over a $4 billion increase in foreign direct investment from $623 million to $4.713 billion.

High investment was not meant to last. Beginning in 2012, foreign direct investment plummeted just as quickly and dramatically as it shot up. Investors likely balked at copper prices that plummeted in the second quarter of 2012. As a result, between 2012 and 2015, foreign direct investments fell $4.2 billion to a mere $196 million last year.

In spite of the massive expansion and contraction of foreign investment in Mongolian businesses, private international mining company spending on their own ventures has kept the GDP from shrinking even though growth has slowed. The exponential growth that started after the 1997 Mongolian Minerals Act peaked in 2013 at $12.583 billion, a 17 percent growth rate, but was followed by a downturn in GDP with growth rates slowing to 2.3 percent in 2015.

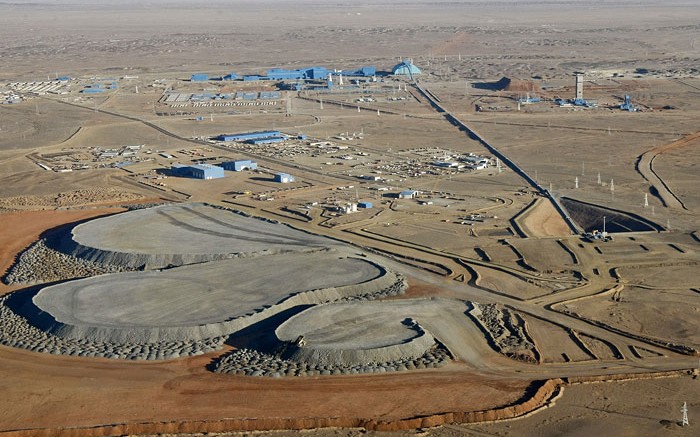

The Oyu Tolgoi mine in the South Gobi. Photo by The Northern Miner.

One such company is Turquoise Hill Resources Ltd., a subsidiary of the Canadian Ivanhoe Mines. It announced a $4.4 billion investment in underground development at its mining sight Oyu Tolgoi on December 14, 2015. Estimated to be the world’s third largest reserve of copper, Turquoise Hill originally invested $6.2 billion in 2013, after years of exploration and analysis, to begin production.

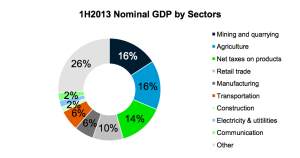

The 2013 Mongolian GDP by Sector as reported by the Mongolian Embassy to the United States. Click to see full economic report.

These investments, and others like them, have helped and continue to be a vital part of the Mongolian economy. In 2013, mining made up 16 percent of the GDP and the exportation of copper, gold, and coal made up 65 percent of exports in 2012.

In spite of goals to bolster the economy, the Mongolian government has not opened the floodgates to capitalist investment in such a way that would allow foreign corporations to lay waste to the Mongolian countryside, people, and economy to benefit their bottom lines. The emphasis is on sustainable and fair growth.

In order to include Mongolian interests in mining decision making, the Mongolian government and Turquoise Hill spent five years negotiating the Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement. The agreement states that the state has a 34 percent equity stake in the mine with the ability to renegotiate their ownership to 50 percent as soon as initial investments have been recuperated.

Additionally, the agreement holds the investor accountable for regional economic development, adhering to national and international environmental standards, contributing to national infrastructure, maintaining a workforce that employs mostly Mongolians, and investment in the education of the Mongolian people.

Leveraging the Oyu Tolgoi mining contract with Turquoise Hill has allowed Mongolia to begin developing more evenly than some of its resource rich peers, who sold extraction permits heedless of local peoples’ needs and health, such as Ecuador. In creating stipulations that require the mine to be staffed 90 percent by Mongolians, with 50 percent of engineers being Mongolian citizens within the first five years of operation, holistic development is at the center of project.

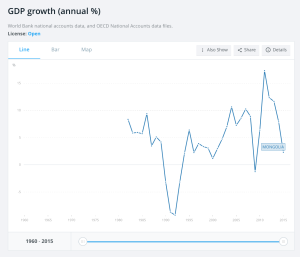

Mongolian GDP per capita from 1960 to 2015. Click an image for an interactive graph.

As a result, GDP per capita increased, poverty rates decreased, and unemployment rates shrank. Since the beginning of development at the Oyu Tolgoi mine in 2011, GDP per capita has grown over 800 percent. The GINI Coefficient, a measure of income distributions in which a value of 0 represents perfect equality and 100 represents absolute inequality, Mongolia is rated a 36.5, a ranking very similar to that of China.

The strength of the Mongolian togrog declined sharply in 2016 in relation to the U.S. Dollar.

Recently, however, growth has not been as impressive as it was in 2011 and 2012 during which GDP growth was in the double digits. In 2015, growth slowed to 2.2 percent. This has in turn caused the Mongolian currency, the togrog, to plummet in value.

Many economists blame Mongolia’s economic downturn on changes in the slowing Chinese economy. China, which is the destination of 80 percent of Mongolia’s exports, has decreased its demand for commodities like copper and coal which has driven down international commodity prices significantly. This serves as a double blow to the Mongolian economy because China is not buying as much and prices are falling in the international marketplace.

Because of slow growth and a faltering Chinese economy, investors who were drawn to invest in the Mongolian government due to the profitability of mining, have quickly sold government bonds, raising the supply of the currency, and further exacerbating the devaluing of the togrog. In order to mitigate these affects, the Mongolian central bank raised interest rates to 15 percent in August. Theoretically, this will curb currency depreciation by incentivizing investors to invest again, which will increase demand for Mongolian currency. But, for now, the strength of the togrog is still a major source of concern for Mongolia.

Regardless of its economic impacts, mining has had some secondary, unintended negative affects on the Mongolian people and environment. As the economy grows, due in large part to the mining industry, there exists an unrivaled concentration of wealth and opportunities in the few cities and mining towns in Mongolia. As a result, there has been a rapid increase in levels of urbanization.

This population shift is common in developing countries because many city and mining jobs are more productive and therefore more profitable than agriculture.

A nomadic herder tends to his herd of yaks near Bulgan Soum in northern Mongolia.

While this trend is the norm in many developing nations, Mongolia’s rich cultural heritage is based in its traditions of animal husbandry and nomadism, which are increasingly viewed as economically uncertain and therefore undesirable ways of life. The increasing frequency of unusually cold winters, called “zuud,” are intensifying movement to urban areas as herds die off on the ice covered steppes. These extreme weather conditions have been attributed to pollution and its affects on climate change.

To move to the city, many families sell what remains of their herds, which have traditionally served as a source of food in the form of meat and dairy, clothing made from the wool of sheep and goats, and even fuel from manure to ward off the frigid winters. Since so many herders have relocated to Ulaanbaatar in particular, the outskirts of the city are crowded with “gers,” traditional felt tents, that lack running water and proper plumbing.

While these ger areas are difficult to manage in the summer months, it is during the winters, when low temperatures average around -28 degrees Fahrenheit, that real problems arise. In order to keep warm and cook, many former nomads living in gers burn coal and wood. Air pollution is so bad in the colder months that it exceeds the World Health Organization’s most lenient standards by 600 to 700 percent.

This creates a spiral of urbanization. As more nomadic families leave the countryside and gather in mining towns and cities, pollution increases thereby worsening and increasing the frequency of hard winters, forcing more families to trade their herds for mining or manufacturing jobs.

Mongolian boys participate in the horse race portion of Naadam, a traditional holiday that celebrates the Mongols’ nomadic roots.

Without intervention, urbanization could potentially lead to the disappearance of the nomadic traditions that have inhabited and characterized the region for over one thousand years.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.