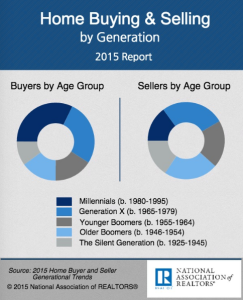

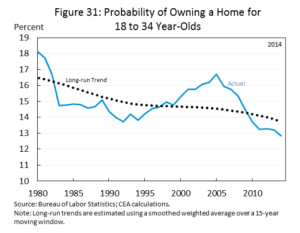

Residential investment currently accounts for about 5% of the United States gross domestic product. Considering the US GDP stands at just under 18 trillion dollars, housing is clearly a significant portion of American spending. As a major driver of economic growth, housing indicates the wealth of the people, but since the 2008 recession, it has taken a dip, and it is important to examine why. At 35%, the largest generational group of buyers consists of millennials between the ages of 18 and 34, but since the 1980s, the probability of this age group owning a home has gone from almost 17% to just under 14%. The question now is whether this is a permanent change or if it is just a fluke due to the economic crisis.

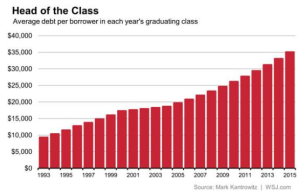

In the early 2000s, credit was very cheap, and this led to banks loaning money to people who probably should not have been given that responsibility. They took this money and bought up homes because they were known as a stable, surefire investment. Eventually, these people struggled to pay back their loans, and the bubble burst, causing banks to suddenly tighten up and be wary of loaning money. This does not bode well for average young adults because they do not have a long financial history to back up their ability to pay off loans. Right now, young adults are also being hit with a plethora of other problems, such as student debt and a flailing job market. The average college graduate in 2015 has to pay back over $35,000, which is more than double the amount borrowers had to pay back only 20 years ago even when adjusted for inflation. What is worse is that 44% of college graduates in their 20s are stuck in low-wage, dead-end jobs. With such shallow income-growth trajectories, millennials are more focused on paying current bills and making rent every month than saving for their future home.

This goes against the fundamental “American Dream,” which is a traditional idea consisting of three entities: job, family, and home. The hope is that with hard work and determination, one can acquire a high-paying job and eventually purchase a home for his or her family. As a result, young Americans have set life goals around hitting milestones to put them on this path, but as illustrated above, this “dream” is increasingly becoming out of reach.

The share of young homeowners has fallen steadily for the last thirty years, which means many millennials have taken up a new, or perhaps old, residence: living with their parents. For the first time in 130 years, the most common living arrangement among millennials is sharing a home with their parents, and over one-third of this generation is choosing to do so. Much of this can be blamed on the recession. Young adults do not have the money for a down payment or the continuous stream of bills stemming from mortgage and upkeep. Additionally, the housing market is not making this any easier with its increasing market prices and decreasing number of available affordable homes. Young people say they will move out the day they can afford it, but that day is looking depressingly out of reach.

For some, this situation is old news. Those who grew up in poor neighborhoods have always been less likely to be motivated to leave their hometown. These young adults probably will not go too far for college, and they are stuck doing low-wage jobs that, even in the long run, will not provide enough income for them to save and eventually spend on their own house. Those in this group are more likely to live with their parents and may be providing for the family just to make ends meet. Their situation is dire, and they are bound to a place that cannot allow them to grow and prosper.

On the other hand, take a look at those who have the greatest chance of being able to afford their own home. These include high-achievers who tend to come from rich backgrounds, move away for college, and settle in popular cities with a concentration of jobs like San Francisco or New York. Compared to the first group, this group has drastically more resources and therefore more freedom to set their own priorities. However, they are still not buying homes, but this could actually signal a cultural shift and a delaying of the whole process. There are many rational reasons why a young person of decent money would want to wait to splurge on a home, and it is possible this is due to a change in mindset.

For one, the rent in the cities mentioned above has reached astronomical, and for many, unaffordable levels. In both New York and San Francisco, the average square footage of a one-bedroom apartment is 750 square feet. This is a comfortable size for at most two people. The median rent per month for this apartment is $2,200 in New York and an outrageous $3,600 in San Francisco. This means that per year, those who choose to live in these cities are committing between $26,400 and $43,200 to solely rent. For many, moving to these cities is not so much a choice as it is the best way to find a career in their desired industry. New York is a financial district, and San Francisco is the land of the start-ups. There are definitely more job opportunities, but as a location gains popularity, it also gets more expensive. This leaves little room for young adults to save a large enough sum for their own property.

Millennials also have this newfound desire for flexibility, and homeownership does not allow that. Many graduates have the mindset that they will take a job for at maximum a few years and then move onto something else. In fact, it is completely normal for millennials to switch jobs an average of four times in their first decade out of college, and more often than not, this career change also results in a location change. This demands the ability to be mobile, and renting means that once the contract is up, renters can move out without having to worry about finding someone else to take their place. Selling a house requires a whole other set of considerations, such as possible remodeling and hiring an agent in order to get the best price. From this point of view, renting property simply provides conveniences that buying does not.

Consider a newly married couple where the wife works at a large insurance company and the husband is a doctor. This couple has moved three times during their time together: once from college to medical school, again for medical school to residency, and one more time for the husband’s first real job. Throughout the years, the couple has accumulated a healthy sum in comparison to others in their age group, but because of their tendency to hop from place to place, they do not see the point in buying a house. Selling after just a few years does not provide much profit, even in high-income areas, and moving without selling the house does not make much sense. Years ago, it was uncommon for people to move across the country multiple times, so there was not much risk involved when buying a house. For young people nowadays, this is rather commonplace, so they have a totally different mindset than their parents did. Norms are changing, and that means cultural decision-making is changing as well.

On top of this, there is currently a shortage of starter homes, so young people have a very limited set of options. Housing starts went way down after 2008, and it is slow going on its journey back to pre-crisis levels. Instead, new construction is now being focused on the luxury side, so homes that used to be entry-level are now priced above what young adults can pay. Because of increasing expectations, the new supply is being adjusted to fit the demand. Getting fancier also means getting more expensive, which only prices out the people who actually want to purchase their first home. This is clearly a vicious cycle.

Money is a driving factor in most decisions. It hides behind other reasoning and provides concrete limits, but maybe it should not be the first thing people blame for the decline in homeownership. Perhaps it is simply a change in the mindset and priorities of millennials that has veered tradition off course.

Product sharing is an idea that can only exist in modern age companies because of not only technology but also the cultural shift mentioned above. One example is Zipcar. It boasts over 700,000 members, which makes it the largest car-sharing company in the world. Members are able to borrow these cars from various locations, and Zipcar covers gas and insurance. These conveniences are highly appealing to many people because this eliminates two large worries associated with owning a car. There is also no need to search and pay for long-term parking, which can reach exorbitant levels in big cities. If people do not want to worry about parking at all, they can turn to Uber or Lyft and simply pay for the ride itself. This “sharing” business model has been repeated across industries, including Airbnb for housing, Rent the Runway for clothing, and Spinlister for sports equipment. The list goes on. Sharing companies are now commonplace, and they are born out of a newfound prioritization of convenience and flexibility.

Regardless of the cause, the decline of homeownership has very real implications, and it is telling about the health of the economy. High levels of homeownership signal a certain confidence among buyers. They believe they can make good on payments, and this means they are earning a comfortable wage. Typically, a family’s largest purchase is their home, and home purchasing decisions are telling of the nation’s economic development. Families exhibit their buying power through what home they choose to purchase, but if they no longer have the desire to buy a home, this affects other industries as well. For example, urban planners who map out entire neighborhoods of homes suddenly have less demand, and construction workers have fewer jobs as a result. There are also real estate agents and others who have fewer sales to make, and the list goes on. Changes in the housing market no doubt affect the greater economy, which is why the decline in homeownership is so alarming.

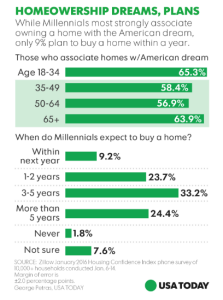

At least at this stage in their lives, millennials simply place less of an emphasis on actually owning items than past generations have, and this translates to a decrease in young adult homeownership. However, this does not mean that young adults do not hope to one day own their own homes. Among millennials, 65.3% still associate homeownership with the American dream, and more than half of all millennials expect to buy a home within the next five years(USAToday). Their plans may be delayed, but there is definitely still a checkbox next to homeownership that they hope to tick off within their near future. The American dream lives on; the millennials just need more time to get there.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.