The “New Compton” is a phrase that has fallen out of the mouths of Compton politicians for decades now. It promises safety and economic revitalization, it whispers hope into an area marked by blight.

It’s easy to single out the crack epidemic of the ’80s and the gang violence of the ’90s as causes for Compton’s economic woes. But whatever the problems in the past were, the economic trials of Compton’s present are exacerbated by something as simple and mundane as a credit rating.

Or rather, the lack thereof.

Because just as a credit rating has a profound effect on where a person can live — and how well — a city’s credit rating can dictate how a city governs itself and how well it can take care of its citizens.

The Hammer

It’s pretty easy for average people to understand the effect a credit score has on their lives. A poor credit score can disqualify them from renting or owning an apartment. It can affect the credit limit available to them when they apply for a credit card. And it affects their interest rate — something that comes into play in big ticket loans like car loans and mortgage payments. The lower the credit score, the higher the interest rate on these loans, as lenders need greater compensation for the risk they’re undertaking.

This means a $100,000 house will end up costing more to the homeowner with poor credit, as he or she has to pay a higher interest rate on top of the actual cost of the house. Assuming it takes 30 years to pay off your $100,000 house, a 1 percent difference on the interest rate would amount to an additional $30,000. This has long term implications on the rest of your budget — whether you can send your child to a private school, how much you can pay for groceries and transportation, and so on.

Cities, governments, and school districts have credit ratings too. And just like the average Joe or Josephine, it affects how they’re able to manage their cities — what projects they can undertake, what services they can provide, even how much they may afford to pay their employees.

“A rating is a third-party review or grade on your financial health, which necessarily includes management, financial management,” said Raul Amezcua, Managing Director for the Public Finance Team at Stifel, an investment banking firm.

Impacting that credit rating is historical performance, as well as the existence of management tools that help a city weather ups and downs — like whether it has a budget surplus.

The highest rating a government or company can receive is AAA.

“I’ve seen everybody from the President of the United States talk about the importance of having a AAA rating and making the right decisions to preserve it, to governors, to mayors,” said Amezcua. “I think it’s a good tool. It’s a hammer, if you will, that makes people have good financial management in place.”

AAA ratings allow companies and governments to issue bonds to investors with a relatively low interest rate attached. Amezcua points out that the kind of people who invest in these bonds are risk-averse. As rule, bonds are perceived to be less risky than equities.

“Investors who buy bonds want to get paid. Principal and interest — on time,” said Amezcua. They don’t like to take the risk of non-payments. If they wanted to assume that level of risk, typically they buy riskier investments like equities, stocks.”

So, what happens if you don’t have a AAA rating? What if you have a poor rating —or even worse, no rating at all?

The same thing that would happen to a subprime borrower getting a loan to buy a house: you are forced to pay a higher interest rate.

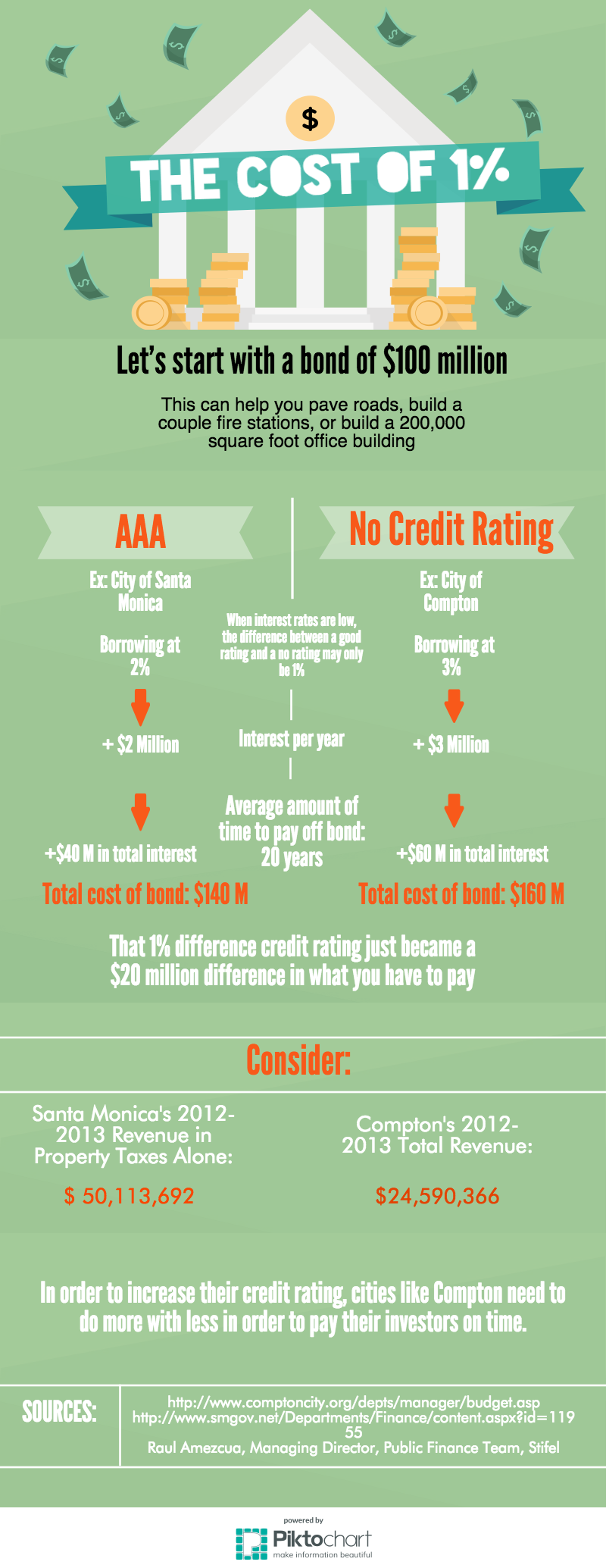

In today’s present economic climate, where the Federal Reserve has not raised interest rates since 2009, the difference in this interest rate may only be 1 or 2 percent, which doesn’t seem like a big deal at all. Until you consider the cost it takes to run a city.

The Cost

Amezcua says another way to look at it is to say, for $100 million worth of projects in Compton, the city of Santa Monica could build $140 million worth, because they have a reduced cost.

“They are spending less money on their capital infrastructure projects, because they borrow at less money,” Amezcua said. “They could have more costs on the street. They could pick up garbage more frequently. They just have more money left because they’re not spending it paying investors a higher interest rate because they’re poorly managed.”

According to Amezcua, the average life of a 30 year bond in the municipal bond market is 20 years — which can amount to a pretty hefty price tag on interest rate alone. But let’s say it’s a loan you need to pay back in a year. Perhaps that effect wouldn’t be quite so drastic.

Amezcua raises the example of a tax and revenue anticipation note, or a TRAN. It is cash-flow borrowing that is necessary for cities and counties who need to pay employees (like police officers and fireman) weekly, but only receive revenues twice a year, when residents make property tax payments.

In 2015, Compton received a 2.2 percent interest rate for a $10 million TRAN. Amezcua points out that the City of Los Angeles did a TRAN last year for a rate of 0.3 percent.

With a 2.2 percent interest rate, Compton has to pay an additional $220,000 in interest. If they had a 0.3 percent interest rate, they would have had to pay $30,000 — a difference of $190,000 on the year.

Amezcua notes that $190,000 is enough money to pay the salaries of two or three police officers, or a good city manager. That’s the sort of budget line item that Compton misses out on,because it has to pay back to its investors.

In this way, the predicament that falls on Compton’s shoulders is the same one that falls on the shoulders of so many Americans with poor credit: to improve their financial standing, they are forced to go without certain goods or services that they can ill-afford to forego.

Unfortunately, Compton earned its credit rating through years of political and financial mismanagement. In 2012, Compton was on the brink of bankruptcy after amassing a $43 million deficit. The city had improperly used money from water, sewer and retirement funds to balance its general fund.

This meant, in 2012, it was virtually impossible for Compton to get a line of credit:

“Officials slashed the city’s workforce last year and sought the line of credit to help deal with cash flow problems in the short term. But that effort ended after Mayor Eric Perrodin sent a letter to the state controller’s office in December alleging that fraud might have led to the city’s financial problems and calling for a forensic audit.”

– Abby Sewell and Jessica Garrison, L.A. Times

Even with new leadership under Mayor Aja Brown, the financial sins of Compton’s past are considered when assigning a credit rating, and are thus hard to scrub clean. Only after years of making payments within the boundaries set by investors can Compton hope to regain the good credit necessary to undertake large projects at a cost that isn’t prohibitive.

And while one could certainly make a strong case that those two or three police officers, or that game-changing city manager, would have a bigger impact in Compton than it would in a AAA-rated city like Santa Monica or Pasadena, the fact of the matter is that investors and credit-rating agencies don’t consider those sorts of things when determining whether they’ll invest in a bond or issue a credit rating.

Which leaves cities like Compton with the continued burden of figuring how to provide more — for less.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.