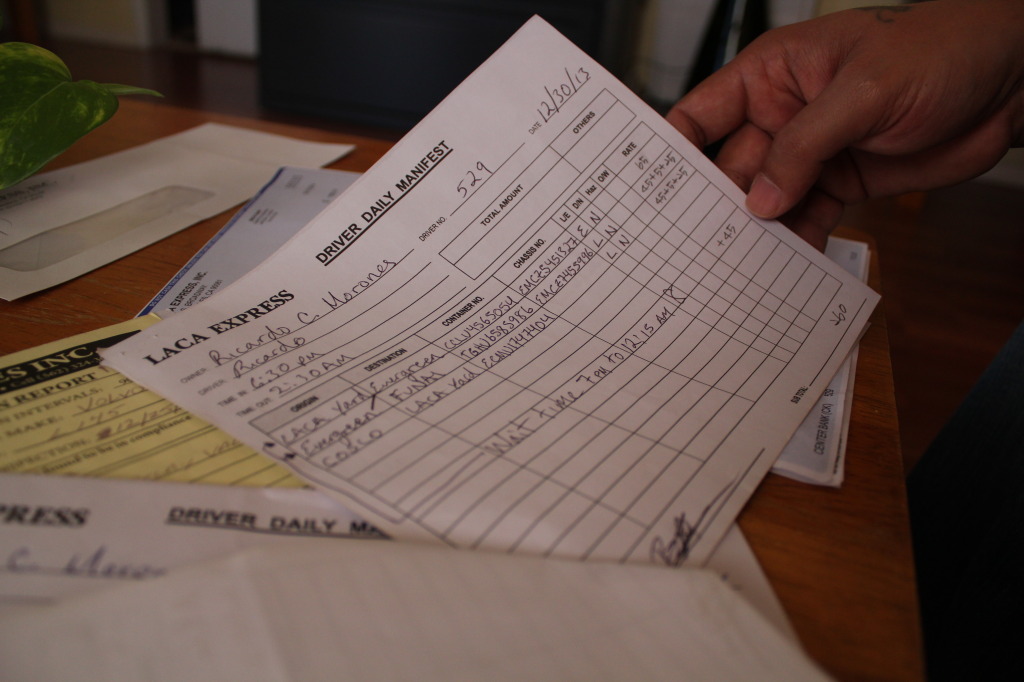

At about $1,700 a month, Ricardo Ceja’s truck driver paystub looks decent. But then come the deductions — for insurance, registration, inspection, parking, repairs, fuel and the truck lease — until Ceja comes up $900 dollars short.

“This is modern age slavery,” Ceja says. “And they’ve been getting away with it.”

He’s been on strike recently against LACA Express, where he works without benefits as an independent contractor hauling cargo to and from the Port of Los Angeles.

LACA frames Ceja’s position as an opportunity for drivers to buy their own trucks from the company, paying in installments, on the way to launching their own businesses. Drivers are paid by the load — $45 for a full container and $20 for an empty one. Sometimes they get bonuses, like $20 for a refrigerated container. In addition, LACA pays 22 percent of their fuel costs.

Ceja sees it as a scam.

“They pay me every week, but they deduct whatever they want,” he says. “They throw you a bone with a string.”

One day, Ceja would like to pay off the truck he drives for LACA. Paying $250 a month, he expects that to take five or six years. Many truck drivers can’t hang on to the job for that long. They have an accident or get sick with an illness they can’t afford to treat without insurance. Or they simply burn out from exhaustion.

Giant cranes at the Port of Los Angeles help transfer containers from ship to truck. | Daina Beth Solomon

Ceja, who came to Los Angeles from Mexico as a teenager and now lives in a quaint apartment in Lawndale, wants to stick it out and become his own boss.

“That’s the American dream, right?” he asks rhetorically. “Having your own business, being able to afford a home, and have a good life and a nice retirement.”

He’s hopeful that, along with the Teamsters’ aid, he can pressure his boss to offer benefits. Mayor Eric Garcetti helped broker a truce a couple of weeks ago, and negotiations are continuing.

Already, Ceja has seen some improvements, albeit minor ones. When rumors of the impending strike began to circulate, LACA increased its fuel payments by 4 percent and cut its lease rates by $30.

A closer look at Ricardo Ceja’s paystubs shows just how much he’s losing — not making. | Daina Beth Solomon

But the company largely seems disconnected from its workers woes, says Ceja. It sent a letter to “all drivers” in October, opening with the message: “We are all same family in the same boat. Let’s try to find the way to live together.”

The note concludes: “We will keep trying to find the way to survive together. Please be patient.”

The memo outlines several new pay rates for various load scenarios. Item number four announces that drivers can earn $30 an hour if they need to wait more than an hour to pick up cargo, not including the time that the port workers halt work for breaks.

According to Ceja, port wait times have abysmal in recent weeks. Drivers should need just one hour – two hours, tops — to drive into the pick-up terminal, check with security, hoist containers onto their vehicles and zoom away. Instead, the process can take up to nine hours.

Disorganization is partially to blame. Lines of trucks wind through the terminal, snaking through a maze of sections marked by numbers and letters. (Or sometimes numbers and letters together, just to add confusion.) Systems are haphazard and frequently change. The first time Ceja first attempted to get a load, he spent three days in confusion before giving up.

“I was running around like a headless chicken,” Ceja recalls. “And people were very rude. There’s a thousand trucks, but no one to talk to.”

The dockworkers, rather than offering help, just bred tension.

“They make more money, so they look at us like we’re trash,” says Ceja. “You can’t say nothing to them because they’ll literally kick you out. The supervisors are on their side, the security is on their side, everybody is on their side — and it’s just you by yourself.”

Since July, nearly 20,000 dockworkers have manned their towering cranes and levers without a new contract. When negotiations similarly stalled in 2002 and employers accused the longshoremen of go-slow tactics, ports along the West Coast shut down for 10 days. Ceja says slow tactics have crept into the system yet again, frustrating truck drivers hoping for speedy, cost-effective deliveries.

Ceja bears no grudge against the dockworkers, however. He recognizes that cooperation is essential to create a robust industry capable of doling out fair wages.

“We all need each other,” he says.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.