Mergers & Acquisitions in 2014 have reached their highest point since the turn of the century — the $1.5 trillion in M & As recorded this year is the most since 2000, according to financial information firm Thomson Reuters.

The theme continued this past Monday, with more than $100 billion in M & As accounted for between Allergan being bought out by Irish pharmaceutical company Actavis and Halliburton acquiring oil company Baker Hughes.

For Allergan, the bio-tech company based in Irvine, the deal was especially sweet. The firm best known for making Botox was the target of a hostile takeover from hedge fund manager William Ackman and Valeant Pharmaceuticals for several months. Not only did Actavis pay more for Allergan — $66 billion, or $219 per share compared to Ackman/Valeant’s reported ceiling of $209 — but vowed to cut funding for research and development much less than the previous offer. Ackman still made out ok, though, since he had been accumulating shares since they were in $120s earlier this year. His 10 percent stake in Allergan saw $2.3 billion in paper gains this Monday.

Halliburton, on the other hand, was already the second biggest oil services company before buying Baker Hughes — which was the third largest. Despite a mixed reaction from shareholders so far, Halliburton believes the deal will lead to “cost synergies” of $2 billion per year and increase the company’s product line , according to Forbes.

Monday’s activity highlights how commonplace the practice has become. The Economist cautioned 20 years ago about the potential pitfalls of combining companies, and that was after a “mere” $210 billion had been registered by September, 1994.

Critics of large M & As point to several potential issues. First, many workers often lose their jobs when companies merge. This was evident when Sprint fired thousands of employees when they were acquired by Japanese telecommunications firm Softbank last year. The deal hasn’t found a way to make the company more of a threat to AT&T and Verizon yet, with Sprint recently announcing 2,000 more people would be losing their jobs.

And in many cases, there are reservations about M & As creating conglomerates that are too powerful — leading to monopolies and oligopolies. The Halliburton – Baker Hughes connection will certainly draw scrutiny from regulators concerned about antitrust violations. Although the deal will not be formalized until next year, shareholders may already be wary — with the company’s shares falling two percent a week after the deal was announced.

This isn’t unique to Halliburton, though. In general, mergers aren’t well received by the shareholders of the company buying out another firm. However, for investors of the company being bought, the opposite is true, because they are normally being bought at a premium. Allergan was bought for a five percent markup of the current share price on Monday, after they had already skyrocketed since the beginning of the year.

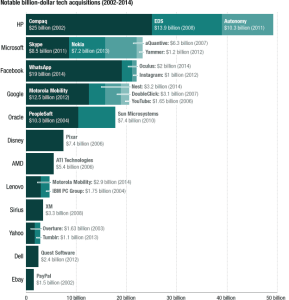

Lastly, the tech industry has been a hotbed for buyouts of late, and the exorbitant prices companies are paying for startups has many thinking this is the second coming of Dot-Com Bubble. What makes these purchases especially tricky is that many times the companies being bought aren’t publicly traded, so deciding on a market value for the business is rather arbitrary. Facebook buying messaging platform WhatsApp for more than $19 billion raised eyebrows for its seemingly over-the-top price. And even though the deals are worth billions of dollars, they can seemingly happen on a whim. Mark Zuckerberg reportedly said he “must have” virtual reality tech company Oculus earlier this year, and closed the $2 billion deal so fast that several high ranking executives at Oculus didn’t even know it was in the works until they showed up for work and found out they had been bought.

While there are red flags to consider when companies merge, recent activity suggests it won’t be slowing down anytime soon.