It is Saturday night. You and your friends are planning to go downtown for a few drinks. Instead of calling a cab, someone takes out her iPhone and books a ride with Patrick. He has a friendly smile, a five-star rating, and a white Toyota—with a pink mustache.

Named as one of TIME’s 10 ideas that will change the world in 2011, the concept of collaborative consumption has proved it is a force to be reckoned with. Service start-ups such as Lyft, Uber, and Airbnb are challenging the traditional models of consumption, giving regular guys like Patrick an opportunity to participate in the supply chain. Before, hopping into a stranger’s car may have been seen as reckless and irresponsible, but Rachel Botsman, co-author of “What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption,” writes about how technology is enabling trust between strangers. She says collaborative consumption is a “powerful cultural and economic force reinventing not just what we consume, but how we consume.”

Technology has often times disrupted the economic landscape. Take Lyft as an example. It is a ride-sharing app that markets itself as “a friend with a car.” The economic transaction is more than just an exchange of service; it’s an experience. Lyft is redefining what a ride service is, while normalizing casual interaction during commodity exchange.

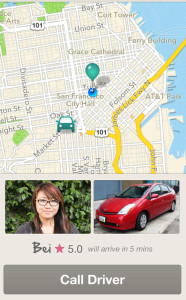

Here is how it works. At any point in time, you can open up the app and hail a friendly Lyft driver around the area.

You enter the car, give the driver a fist-pump, and he or she entertains you with a friendly conversation as you are dropped off at your location. The transaction is processed by Lyft so you avoid the awkward paying and tipping process. Using Lyft is vastly different from using a taxi service. Lyft has become popular especially with the tech-savvy and thrifty Millennial generation. The company raised $60 million in its third round funding last May with venture firm Andreessen Horowitz and the company has grown to be available in 22 cities.

According to TechCrunch, Lyft is currently growing at a faster pace than its main competitor, Uber, with a 6% growth rate disclosed by its co-founder, John Zimmer (TechCrunch). Some point out the numbers can be misleading since Lyft currently has a smaller revenue base than Uber. However, when Uber raised $307 million in Series C funding last June, Lyft caught up to having one-third of the weekly ride volume Uber had across all its products. If we dive further into the success of Lyft, we can find there are multiple economic forces at play.

“There’s an app for that” is a now common response to everyday problems. Technology of apps and proliferation of mobile phones have allowed companies like Lyft to reduce transaction costs. People are able to conduct business with private individuals rather than a chain. This process of disruption has reorganized the protocol of commodity exchange. In Lyft’s case, the app redefined the economic structure by asking for “donations” rather than charging “fares” for payment. Since Lyft does not employ a specialized workforce, it came up with a new form of transaction in order to enter the market. The legality of this is as fuzzy as Lyft’s iconic pink mustache, evidenced by the app’s ban in certain cities like Seattle. Major cities like Los Angeles requires Lyft to charge a set fee to continue its service, but the majority of Lyft locations still operate on “donations.”

Perhaps ironically, through innovation, our generation is reverting back to a peer-to-peer localized model. “Collaborative consumption” is often interchanged with “shared economy.” The act of sharing is deeply ingrained in the Millennial culture. Millennials love to share articles, tweets, pictures, location, etc. It seems natural that this behavior trickled down to more tangible things like clothes, cars, and even homes. Economic sluggishness over the last few years has also contributed to this phenomenon, as more people are trying to find ways to make money off of their unused or under-utilized assets.

Think about it. You have a car and a driver’s license. You consider yourself to be a responsible driver, and you give rides to your friends all the time—why not start getting paid for it? Patrick bought into the idea, joining Lyft to make some money on the side.

“I needed a second job to help pay some bills and also to help save up for grad school. I do see myself doing this long term because I can make some extra cash and not have it interfere with my regular work schedule,” he says.

Lyft takes a 20% cut from every transaction. There are also “Prime Time Tips” that escalate rates during high-demand periods (i.e. 11pm on a Saturday night). These tips can go as high as 70%, but the entirety of the increase goes to the drivers. Due to the reduced transaction cost of using a casual workforce and conducting financial transactions online, Lyft fees are also generally cheaper than regular taxi services. Katherine, a college student from California, says she uses Lyft because it is more convenient and affordable.

“I use Lyft because it feels more personal and I feel like I can trust the drivers. Plus it’s convenient to find a car from an app on my phone – I never know which number to call for a taxi or what service is better than another. Plus it’s cheaper. A ride to downtown via taxi can be $14, while using Lyft, I can get a rate as cheap as $8.”

It seems like everyone wins—well, except for the taxi and limo service industry. Formally trained drivers who are screened in a testing and licensing system are now competing with normal civilians. In essence, the barriers to entry to the transportation industry has been compromised. However, this does not mean Lyft does not take safety seriously. In some aspects, Lyft’s screening process is harsher than some taxi companies, with higher age requirements, and stricter standards on criminal records. For instance, Lyft requires no reckless driving or DUI within the last seven years, when the City of Los Angeles only requires three years. In addition, Lyft links your Facebook for verification and provides insurance of up to $1m for the drivers. The car also has to be clean and presentable.

There have also been tensions between governments and the new model. In 2012, the California Public Utilities Commission issued “cease and desist” letters to Lyft along with other similar services. Although the knee-jerk reaction may be the issue of safety, there are many factors contributing to the debate of this new business model. Taxi and limousine companies who once enjoyed monopolies are heavily lobbying against legalizing these services. In addition, many cities rely on the regulation fees these companies pay to operate, fees private ride sharing programs are not obliged to pay.

“To me it’s a really dumb debate,” Patrick says.

“The real concern for the state of California and other states that Lyft operates in is that they see private ride-sharing programs as entities that are taking money from them. They hide under the issue of safety, but their arguments are based off of taxi companies having to pay fees regulated by the state while private ride sharing programs do not. How does that equate to being concerned about passenger safety? It’s really ridiculous.”

The issue of safety is always brought up in these debates. However, it seems like Millennials have more faith in strangers. Katherine says, “the idea of communicating even with a stranger online isn’t quite as daunting anymore.”

“There’s a growing inherent trust between young people in this generation (twenty-somethings), so doing things like calling a cab or organizing a ride share through an app or online service doesn’t seem so out of ordinary, and most don’t think anyone is trying to scam them.”

Patrick says the age of his passengers range from 21-45, which is consistent with the wide belief ride-sharing is embraced mostly by the Millennial generation. Botsman asserts that we now live in a global village, and there is a new importance placed on reputation. In Lyft’s case, transactions are followed by a rating system, from these reviews drivers and users leave a trail. If you average less than 4.5 stars, you are in danger of being dropped. Our ability to collaborate is quantified into a form of “reputation capital,” and it is put in public display, ultimately determining our access to collaborative consumption.

Last September, the State of California became the first state to regulate ride-sharing, or what is now newly dubbed as “transportation network companies.” Depending on how these new rules perform, other cities may follow the California framework in the future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.