Picture living under the threat of attack within the town you were born in. High walls and towers divided the very streets you walk to school, work, or a place to meet with friends. The threat of bombs or the reality of violence plaguing your every step. Imagine growing up, watching four decades of violence tear your city and country apart.

That was what living in Northern Ireland was 20 years ago. The “Troubles” as they are commonly referred to, were fought primarily between opposing paramilitary groups of either protestant unionists or Catholic nationalists in Northern Ireland. Civilians were often caught in crossfire and fell victims to homemade bombs or stray bullets.

An estimated 30,000 people were imprisoned for paramilitary offenses during the troubles and over 100 peace walls, adorned with sectarian messages and barbed wire are still standing in the city of Belfast. Though the people of Northern Ireland would do without more literal and physical walls, there’s a chance there might be a few more added in Northern Ireland.

In 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the EU. Some hailed the results of the referendum has a chance for the UK to negotiate trade with Europe on its own terms, while others saw the results has a sign of increased xenophobia and warned that the choice would result in unemployment.

However, the majority of Northern Irish citizens voted to remain in the EU, According to the BBC. And though the U.K. and the European Union have until March 29, 2019 to set trade and border terms for Brexit, the clock is ticking for a solution for Northern Ireland.

The problem starts with an an almost 20 year old pact known as the Good Friday Agreement. It ended sectarian violence and created an open border between the two countries. Because of this, citizens of Northern Ireland have the option for Republican passports. In the days of the hard, militarized border between both countries, the border was “a frontier of milk smugglers, gun runners and frequent clashes between British soldiers and Irish Republican Army cells”, according to the Washington Post. Today, many Irish citizens feel that there is a sense of relative peace.

“This city, this country, is like a woman who has given birth,” said Gerry Lynn, an amateur historian of the city Londonderry, to the New York Times. “All the trauma, the pain and the fighting are over. We’ve come out of the Troubles — out of black and white and into color.”

However, in March of Next year, Northern Ireland will leave the EU with the UK, and it’s brother, the Republic of Ireland, will stay, putting the open border policy between the countries up in question.

In response, the EU has offered that the border between the two countries remain the same, the UK is adamant that changes must be made. Regardless, the U.K. and the European Union have until March 29, 2019 to set trade and border terms for Brexit.

While a hard border could stir up memories of a militarized pass in some, it would also disrupt the “frictionless” trade Northern Ireland is able to benefit with its proximity to an EU country. Still, Northern Ireland’s government has created some friction of its own. It’s government has been in deadlock since January 2017. In affect, they’ve been kept out of Brexit negotiations and Westminster is set to bargain on their behalf.

In July, Trevor Lockhart, Northern Ireland chair of the Confederation of British Industry expressed frustration with the UK government over the issue.

“We find ourselves in a set of circumstances where the solutions that will work for Northern Ireland economically, don’t work politically,” Lockhart told BBC Inside Business. “And, those that work politically, don’t work economically.”

If the UK and the EU don’t reach a set agreement, a “hard brexit” would take place as all trade would be cut from the EU. According to Vox, this could temporarily halt air travel and make for empty supermarkets. It would also reinstate a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, throwing 20 years of peace into jeopardy.

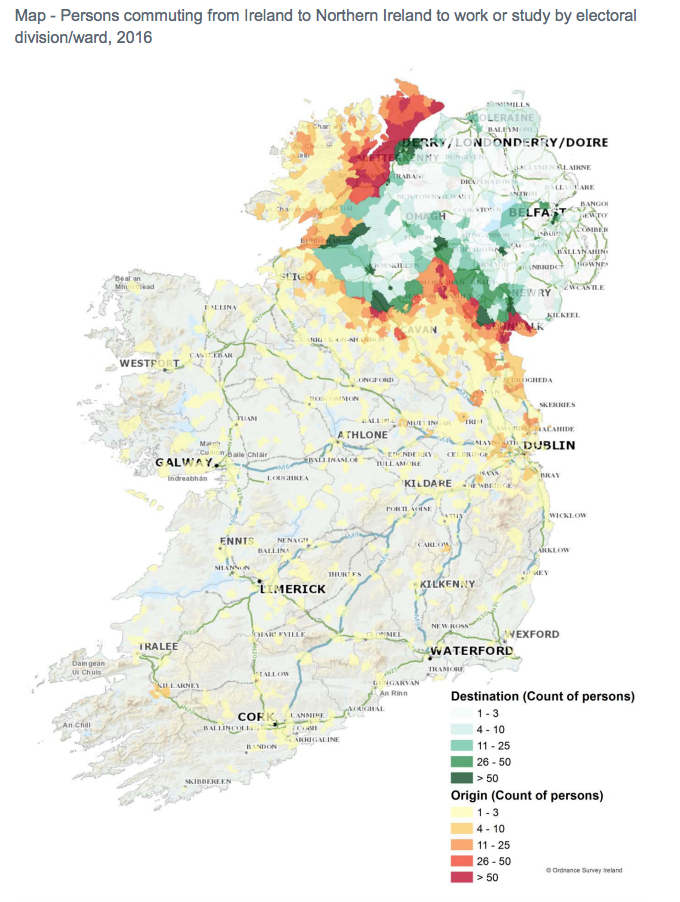

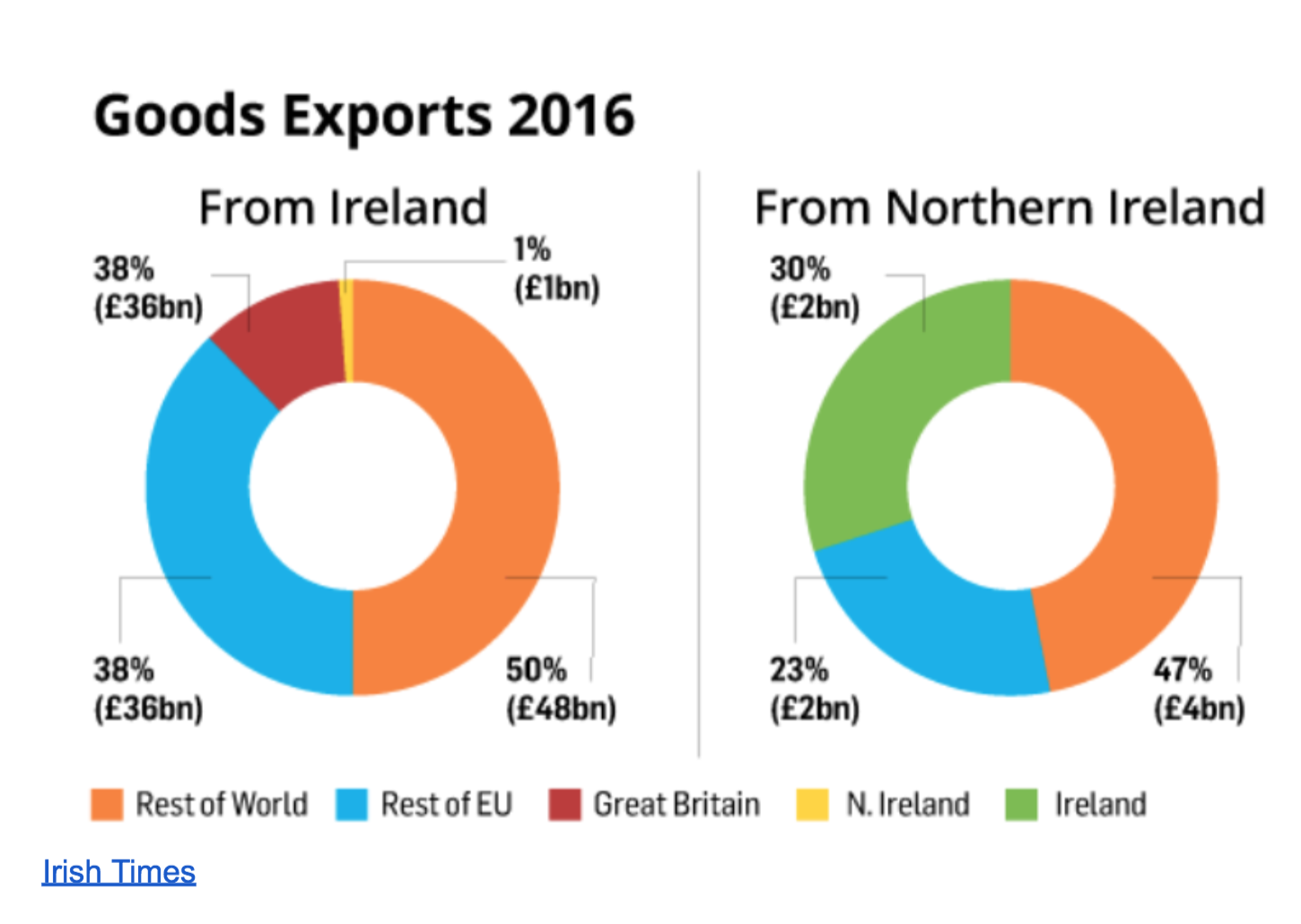

A hard border between the countries could do more than reignite old grudges from the last half of the 20th century. It would bring a halt to the movement of goods, capital, services and people that Northern Irish businesses and workers so heavily rely on. According to the Irish Times, 30 percent of Northern Ireland’s exports or £2 billion were sent to the Republic of Ireland in 2013. Over 50 percent of Northern Irish exports go to the EU.

Republic of Ireland in 2013. Over 50 percent of Northern Irish exports go to the EU.

These exports are largely food products, live animals, machinery and transport equipment. A lot of these jobs are performed by low-skilled migrant workers that receive passage into Northern Ireland through the European Union, according to a report from the Migrant Advisory Committee.

Still, the rest of the U.K. is Northern Ireland’s single largest primary market for external sales. Nonetheless, nearly three-quarters of exports to Ireland come from small businesses with fewer than 50 employees along the border.

Disruption in cross border-traffic has other ramifications as well. Over 177,000 trucks and 250,000 vans that cross the border for trade every month would be subject to customs duties if a hard border was reinstated, according to the Financial Times. This transport does more than bring goods over the border for sale in small shops and supermarkets. Bailey’s Irish Cream, for example, is manufactured from resources from Northern Ireland the Republic of Ireland, and involves over 5,000 border crossings per year, according to the Atlantic Council.

Northern Ireland’s economy continues to experience challenges of its own. Poverty rates in the region are higher than the rest of the U.K. The children of former prisoners can still be barred from from certain jobs while their parents cannot get public sector positions or insurance. In addition, Northern Ireland has received over £470 million dollars from the U.K. for peace programs in communities that are plagued by both by whispers of sectarian struggles and economic hardship.

On October 11, Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator announced that Customs and VAT checks, as well as compliance checks will not be performed at the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, according to the Irish Times.

However, Barnier was unclear as to the nature of system that would be implemented with the Brexit deal.

“There will be administrative procedures that do not exist today for goods travelling to Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK,” said Barnier. “Our challenge is to make sure those procedures are as easy as possible and not too burdensome, in particular for smaller businesses.”

That same day, 21 of Northern Ireland’s leading business organizations released a public letter to Theresa May, demanding that she take note of upcoming labor shortages, as migrant forces will be forced to move south to the Republic of Ireland if the current negotiations are approved.

“Unfortunately, it fails to provide the necessary solutions and we believe it is therefore critical to create an immigration policy with sufficient flexibility to address Northern Ireland’s labour needs,” the letter states.

Are the deadly “Troubles” set to return if a solution is not reached? At this point in the negotiations, it’s hard to tell. However it is important to consider the economic ramifications of repeating one dangerous memento from the past: a hard border.

Sources Note: All works cited have been properly hyperlinked. Ireland map provided by https://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/newsevents/documents/census2016profile6-commutinginireland/Cross_Border_Commuters_2016_v2.pdf.