These images above are some of the most recognizable icons in the South Korean entertainment industry. The Korean Wave, or hallyu, is still going strong, continuing to shape East Asian culture and trickling to parts of Europe as well. As an outsider, it is easy to ask, “What makes Korean entertainment so great?” What has made this tiny peninsula–divided in half–an Asian entertainment powerhouse?

The success of South Korea’s entertainment industry can be traced back to the Kim Dae Sung Administration in the late 1990s. During this time, the government’s investment in cultural products increased dramatically. One motivation was to strengthen its domestic market against the Japanese cultural products lingering from the colonial days. Another reason was to recover from the crippling Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, when the country’s GDP dropped 7%. In order to reinvigorate the economy and to raise South Korea’s global profile, President Kim put his faith into the entertainment industry, planting the seed of the hallyu phenomenon. In 1998, the Culture Ministry executed its first five-year campaign, including an increase of culture and fine arts departments in colleges. In 2002, the ministry opened the Korea Culture an Content Agency to encourage exports, sparking the beginnings of the Korean Wave, and injected funding into the Korean Film Council. The results were astronomical. The size of South Korea’s entertainment industry, jumped from $8.5 billion in 1999 to $43.5 billion in 2003. Cultural product exports were so insignificant before 1998 that the government could not even provide figures. Five years later, the number would grow to $650 million.

According to a Oxford Economics report titled, “The economic contribution of the film and television industries in South Korea,” the film and television sector have directly contributed 7,749 billion Won to the South Korean GDP in 2011. It has also supported 67,600 jobs and 3,752 billion Won in tax revenues. Average growth of this industry from 2005-2011 has been 10.7%. From this figures, it is clear this industry provides direct support to the country’s economy.

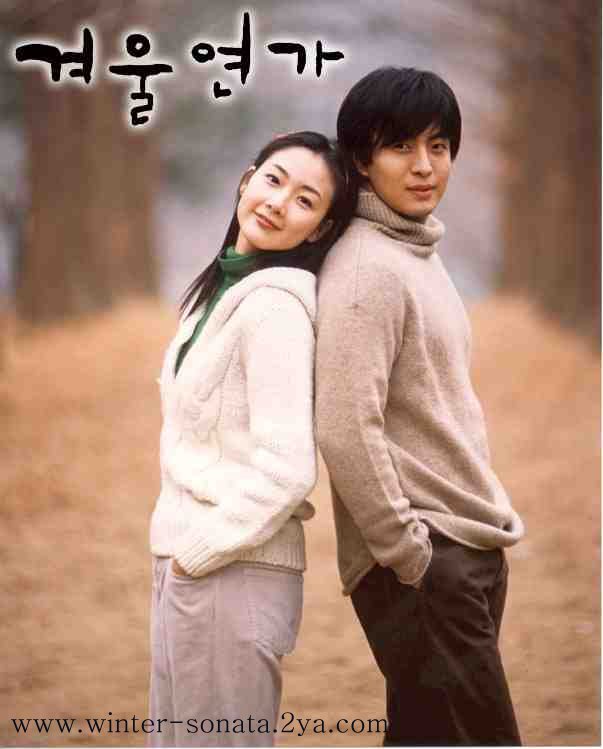

Cultural exports have promoted tourism and business into Korea, particularly from South East Asia. Past work by the Korean International Trade Association (KITA) suggested that Hallyu related tourism amounted to $825 million in 2004. I definitely experienced the impact of hallyu when I visited Seoul for a cultural immersion program. The hot tourist spots were cafes that were themed with a certain popular drama (for instance, the “Coffee Prince Cafe”). There was a statue of the famous lovers from the classic soap opera, Winter Sonata, one of the most successful Korean dramas to date. Many tourists sign up for hallyu-themed tours that take visitors to production sites of famous dramas and films.

What South Korea ultimately gained from their investment in entertainment was soft power. There have been instances where the government leveraged its cultural exports as means of diplomacy. For instance, the official Korean Overseas Information Service gave airing rights to “Winter Sonata” to Egyptian television. They even paid for Arabic subtitles in hopes of generating positive feelings toward South Korean soldiers stationed in northern Iraq.

Another crucial factor of the Hallyu wave has been the web. There is greater access to content than ever before. Anyone can consume foreign content with the swipe of their phone. Online fan communities were formed to share and distribute Korean content. Youtube channels or content websites like mysoju.tv effectively crowd-source translators, graphics personnel, and coders to recreate original Korean content with subtitles and high quality streams. In 2010, an website turned app called “Viki” was launched by a group of Harvard and Stanford students who aggregated the fan-created content to one platform. According to their website, “Viki, a play on the words video and wiki, is a global TV site powered by a volunteer community of avid fans.”

It seems South Korea’s investment in entertainment exports was money well spent. I am scheduling a 20-hour binge session of “Alien from Another Planet” after finals as we speak.