Before jumping right into what I want to talk about for this final project, I want to take some time to explain what Abenomics is. Basically, it’s a term derived from combination of Abe + economics. It refers to the economic policies implemented by Shinzo Abe, the current prime minister of Japan, since the December 2012 general election, which elected Abe to his second term. Using monetary policy to tackle the 15-year long deflation problem and doing anything to try to reach 2% inflation a year is Abenomics in a nutshell.

Abe has since 2012, tried to revitalize the slow growth of economy by using “three arrows” of “a massive fiscal stimulus, more aggressive monetary easing from the Bank of Japan, and structural reforms to boost Japan’s competitiveness”.[1]

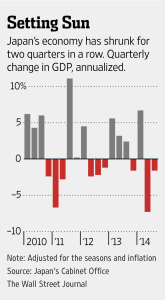

Did Abenomics improve Japanese economy? Well, no one seems to be sure about this. With the third quarter reports that have been announced a few weeks ago and with coming up election in Japan that is going to be held on the 14th, articles about whether Abenomics is a success or not are flooding. There is a huge controversy even among intellectuals on whether Abenomics is actually working or not. It’s hard to tell. However, one thing we know for sure from the official numbers is that Japan is in recession whatsoever.

In November, Japan has officially slipped into a recession despite Abe’s ambitious plans to revive the economy. Everything seemed to go fine until quite recently. In the first quarter, Gross Domestic Product increased by 1.6%. 130,000 new jobs have been created every month since Abenomics started. The excessive quantitative easing by Bank of Japan sharply weakened the value of Yen. This helped big exporters such as Toyota and Sony, driving up company profits to almost a double and increasing stock prices. The new economic measures also resulted in a slight increase in wages and hike in consumer spending.

Sadly, delight in Japanese economy did not last long. As Abe anticipated, prices for goods also began to rise, however, this was mainly due to the weak currency pushing up import costs instead of increase in consumer demand, which meant people’s actual income value has been negatively affected.

To make matters worse, the government made a decision to increase the sales tax from 5 to 8% in April in order to make up for the national debt created by Abe’s radical economic policies. What this means is that Abe’s policy that was trying to encourage people’s spending only resulted in making citizens feel more ‘squeezed’.

Deflation cannot be fixed without increase in consumer spending. Consumers not spending money means demand is low in the market. Because demand is low, suppliers have no choice but to lower the prices to create demand. The whole point of Abenomics is to activate the stagnant economy by making people spend money. Nonetheless, despite Abe’s struggling efforts, nothing seem to be easing the problem as of now.

As I have been doing research, I have realized that it’s not a matter of how many jobs Abe is creating or how much profits corporations are making. It’s rather more about how the money flows in the market through domestic consumption, which accounts for 60% of Japanese economy. I quickly realized it was people’s lack of confidence that’s really hurting the economy. Therefore, I wanted to find out the fundamental reasons to why Japanese people are so reluctant to spend their money. [2] I tried to give my best reasoning behind it but please remember that my hypotheses on why Japanese people are not willing to open up their wallets are entirely based on my assumptions drawn from my own informal research. They are not scientifically proven or anything.

First of all, my assumption is that it has to do a lot with Japanese culture and people’s characters. I know each and every one is unique in their own ways but I also understand that culture is something that cannot be easily disregarded. People get influenced by the culture they live in and it’s one of the biggest things that shape a person’s character.

Everywhere I looked, most generalizations about Japanese people’s characters were that they were 1) polite, 2) hard to become friends with and 3) hard-working. Among these, polite appeared the most; according to JapanToday, the number one word that describe Japanese people according to foreigners is polite or reigi tadashii in Japanese[3]. Now some of you may be wondering how being polite has to do with people not spending money. It was hard for me to find the connection in the beginning as well, so I decided to conduct a little interview with my Japanese friend Mario. The interview was very informal; it was done online through facebook chat. Mario Fukuo is an undergraduate student at Kwansei Gakuin University in Osaka studying economics. The conversation has been edited slightly to make it seem more assignment-friendly.

Me: “I am trying to find the connection between Japanese people’s characteristics of being polite or their other distinct traits to why they are so reluctant to spend money. Do you think you can explain this to me?”

Mario: “Yeah I definitely see a connection. I think it’s not that Japanese people are stingy. We just like to be vigilant and wary about the future.”

Me: “Hmm.. I don’t understand. I still don’t see the connection. Can you please explain to me more in depth?”

Mario: “Japanese people are definitely suspicious. Being polite can be a very good thing but it also means we don’t easily show our personal thoughts to other people. Also, we are very careful and the last thing we ever want to do is cause nuisance or harm to others.”

Me: “Sorry, I still don’t understand how that has to do with people being careful when spending their money.”

Mario: “Well, as in my case, the last thing I want to do is get money from my parents after I graduate from school. I don’t want to be broke in the future and ask you or my other friends to lend me some money. I don’t want to let my family suffer because I don’t have any money saved when I get fired from work. I mean, nobody wants that but Japanese people are way more extreme when it comes to things like this. Do you get what I mean?”

Mario: “Also, as I mentioned, I don’t really trust others or the government. In the end, I am the one who has to be responsible for myself. This is the common notion among Japanese people and this is the big part of the reason why we are so careful when it comes to spending money. We want to be ready for whatever will happen in the future.”

I have arrived at two conclusions from my own little research. The first conclusion is that word polite can mean personal and individualistic in this context. This also means Japanese people are more suspicious and reluctant to trust other people or the government which naturally lead to saving up money for the future. My second reasoning is that because Japanese people are so polite, they don’t want to be a burden to others (friends, family, etc.), therefore this leads to them saving up money right now so that they won’t have to ask for help and support even when they face hardship.

My second assumption on why people don’t open up their wallets so easily has a lot to do with the recent history of Japan. I think it has a lot to do with the Lost Decade (Ushinawareta Jūnen) referring to the years from 1991 to 2000. Recently, the new phrase Lost Two Decades are often being used as well which refers to early 1990s to the present. Over the period of 1995 to 2002, GDP fell from $5.33 to $3.98 trillion and was at $4.90 trillion in 2013 in nominal terms. [4] This is the time after the Japanese asset price bubble collapsed causing an abrupt end to Japan’s strong economy in the beginning of 1990s.

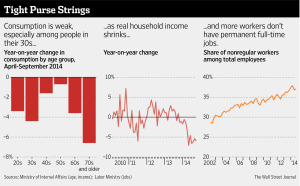

According to this chart made by The Wall Street Journal, consumption is weak especially among people in their 30s. My guess is that it has a lot to do with them being brought up at a time when Japan hit crisis. These people were born and raised until around age of 10-15 at a time when there was huge prosperity in Japan. During 1988, 33 Japanese corporations made it to the top 50 world’s biggest corporate list. [5] However, things started to change all of a sudden–Japan has lost international competitiveness and many corporations had to fend off competitions from rival corporates based in China and South Korea. As a result, employment rate dropped as well; a huge part of workforce had been replaced with temporary workers who get lower wages and less benefits.

Although economy has been made much more stable comparing to the Lost Decade, those who have experienced it are still very careful about the future. People in their 30s right now who have seen their fathers lose their jobs and experienced abrupt change and who have come of age at a time when economy was still shaky are especially scared of the future. This is why confidence just cannot grow. Obviously if government is not doing well with the economy, how are these people likely to get confident about the future and start spending money right?

My third assumption is that decrease in unemployment rate is only nominal. It in fact does not really reflect real world situation.

I conducted another mini-interview over facebook with my other friend from high school, Tairei Natsuki who is studying law at the University of Tokyo to hear about what job market situation is like in Japan.

Me: “You are graduating soon too right? Do you know what you are going to do after you graduate from college?”

Tairei: “I am graduating in March and I am planning on going to law school after this.”

Me: “What is job searching like for your friends who are not planning on going to law school or other grad schools?”

Tairei: “It’s really hard. It’s even hard for students who graduate from my school (University of Tokyo is the number one university institution in Japan). I know one extreme case. I have a good friend who goes to Waseda University (one of the best private universities in Japan) that sent 100 resumes and had interviews with 30 companies. He at last got accepted by JR-East (railway company) and Japan Airlines.”

Me: What about those who don’t go to a good college if even those who go to a good university. It must be so much harder for them.

Tairei: A lot of people end up being the so called “freeters”. This is a combination of two words free + Arbeiter, which refer to part-time job in Japan. Many people are choosing to go this path this way because companies are still not offering enough full-time job offers.

According to The Wall Street Journal article, “a third of the workforce comprises so-called nonregular workers—temporary, often part-time employees who typically earn less than those who have the security of full-time permanent employment.”[6] Being a temporary worker means having an unstable standing in society. This is another factor that leads to people feeling insecure about the future and making them hesitant to spend money.

As a whole, consumer confidence is the biggest challenge Japan must overcome to revive its economy. It is the conviction Japanese people need to make the economy grow–the assurance that future is going to be better as they move forward. What Abe needs to do right now is not just simply printing out pages and pages of money, what he really needs to do is find a way to make his people happy and have high hopes about the future.

[6] http://www.wsj.com/articles/japan-consumers-feel-squeezed-and-thats-a-problem-for-abenomics-1416410445?KEYWORDS=abenomics

[5] https://mirror.enha.kr/wiki/1980년대%20일본%20거품경제

During the time, Japan was the second biggest but saw an abrupt change in their country when they started going to school and came of age at a time when economic challenges were still there.

[4] https://www.google.ae/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&met_y=ny_gdp_mktp_cd&hl=en&dl=en#!ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=ny_gdp_mktp_cd&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=region&idim=country:JPN&ifdim=region&hl=en_US&dl=en&ind=false

[3] http://www.japantoday.com/category/lifestyle/view/the-top-10-words-to-describe-japanese-people-according-to-foreigners

[2] http://www.scmp.com/business/economy/article/1643196/does-japans-recession-mean-abenomics-has-failed-or-needs

[1] “Definition of Abenomics”. Financial Times Lexicon. Retrieved 28 January 2014.