As 2019 comes to a close, it is safe to say that Netflix has successfully disrupted the entertainment landscape and dominated the TV and film industries. On Monday, the company received 34 Golden Globe nominations, 17 in film categories, and 17 in television categories. Streaming services completely shut out the four major networks—Fox, ABC, NBC, and CBS—for the first time in history.

Netflix has many achievements to flex from the past decade. In the first few years, Netflix became available on mobile devices and launched in countries all over the globe. In 2013, it released its first slate of original shows, including House of Cards, Arrested Development, and Orange Is the New Black. After the success of these shows, the company raced to produce as many pieces of original content as possible.

Netflix’s first feature film, Beasts of No Nation, made its debut in 2016, along with television show Stranger Things that would soon become a critically acclaimed global phenomenon. In 2017, the platform reached 100 million subscribers worldwide, putting the company far ahead of its competitors, Amazon Prime (100 million) and Hulu (25 million).

In the past two years, Netflix has been able to boast statistics such the 64 million Netflix households that watched the third season of Stranger Things in its first month, or the 26 million that have viewed Martin Scorsese’s film, The Irishman during its first week on the platform.

With industry award domination and over 150 million subscribers worldwide, Netflix has become a strong force to compete with in entertainment production and distribution. However, the company has run into a problem in recent years that could shake its core business model: the competition of the streaming wars.

The Business Model

Netflix has grown into the behemoth it is today through the following cycle: gaining subscribers and, therefore, revenue, spending the capital on new content, and in turn attracting new subscribers. Netflix drew in its original subscriber base by licensing content from Hollywood’s film studios and television networks. It was a win/win situation: Netflix received content to attract paying subscribers, and studios and networks gained revenue from films and shows that had passed their lucrative windowing period or were no longer on the air. Shows such as Friends and The Office are highly popular on the platform.

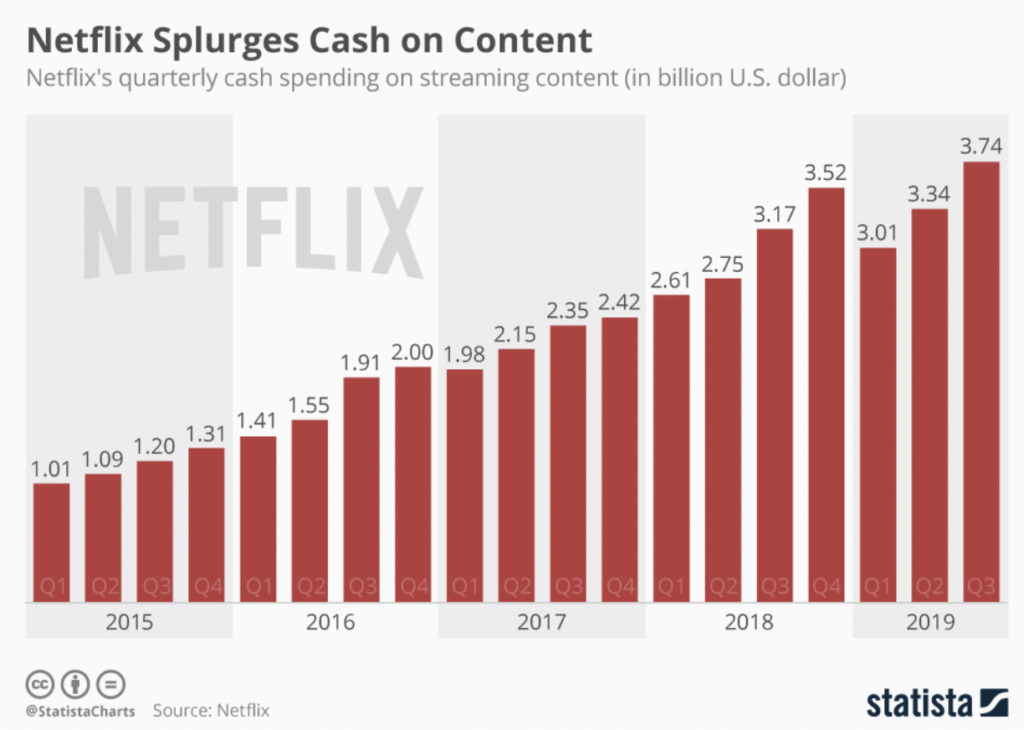

When it comes to original content, Netflix does not bring in enough revenue to cover its production expenses. So, it has burned cash and turned to the debt market for support; at the end of 2018, the company had $10.4 billion in long-term debt. The company sees that investment in content now will bring profitability in the long run when it saturates the worldwide market. This year alone, Netflix spent about $15 billion on original content.

However, the recent launches and announcements of new streaming platforms such as Disney+, HBO Max, and Apple TV+ have shaken subscribers’ and investors’ faith in the company.

The Streaming Wars

When their licensing content to Netflix, legacy media companies had no idea that they were feeding a beast that would end up being a major competitor. When they came to feel the effects of streaming and its impact on cable cutting, many companies stopped in their tracks to put a substantial amount of time and investment into the streaming trend.

Since early 2018, Disney, NBCUniversal, and Warner Media have launched or announced their own streaming services. On top of that, tech companies such as Apple and Facebook have started their own SVOD services. A new mobile-centric player, Quibi, will also enter the market in spring 2020. The rapid crowding of the SVOD market is termed “The Streaming Wars”; American households are only willing to pay for 3-4 subscription services, and some platforms are bound to become shut out of the market.

The competition of the streaming wars creates three main problems for Netflix:

- Licensed content from other media companies is being pulled from the platform, which may drive subscribers to other platforms where their favorite content is available.

- The must be able to spend and rely on its original content for years to come. This means that Netflix will most likely continue to accumulate more and more debt.

- Competitors are undercutting Netflix’s current pricing model of $12.99 per month; Disney+ costs $6.99 per month, while Apple TV+ is on the market for $4.99 per month. This issue may cause subscribers to jump ship if Netflix content becomes less desirable than that of another platform.

The Stock Market Story

Netflix’s stock reflects the issues that the company has faced and may indicate what is ahead. Investors have already begun to worry about the repercussions of the problems explained above, and since the start of the streaming wars, Netflix has lost a bit of its edge in the stock market.

As of 1:00 pm EST today, Netflix’s (NFLX) stock is worth $296.21 per share.

However, about a year and a half ago, in July 2018, the stock closed at an all-time high of $418.97. What happened?

- Falling Short on Projections

Netflix’s stock price took a deep dive in after-hours trading when it reported its Q2 earnings in July 2018. The company had projected a gain of 6.2 million subscribers, but it ended up falling short, drawing 5.15 million instead. Some investors became worried, while others saw it as a single quarter blip.

- Negative Cash Flow

The stock fell again after Q3 earnings reported a negative cash flow moving in the wrong direction. Free cash flow in the third quarter for 2018 was -$859 million, compared to 2017, which saw -$465 million. CEO Reed Hastings explained that the gap between positive net income and cash flow deficit was necessary to create original content, which is the primary driver of capital.

- The Content Competition Begins

Another factor that likely hurt Netflix’s stock price in Q3 was the announcement of The Walt Disney Company’s upcoming streaming service. The beginning of the competition signaled that Netflix might, in the near future, lose market share. After closing at $374.13 in September, share prices fell to $301.78 at the end of October—a 19% drop in the stock.

- Subscriber Losses

The share price made its way back up to the $385 range during the first two quarters of 2019 and took 12% fall after the second-quarter earnings were announced. Netflix reported a loss of 126,000 U.S. subscribers, the first time since it had a negative subscriber gain since 2011.

In September 2019, several analysts provided negative commentary that spooked investors. Share prices suffered a 5% drop but have slowly made their way back to the $300 mark since.

Netflix’s stock story shows mixed opinions on whether or not it will see growth and be a relatively safe investment for the future.

The pros of investing include potential subscriber growth, expanding operating margins, and international expansion and strategy, management team, and strong original content.

The cons include subscriber deceleration, valuation, increasing competition, losing licensed content, and content costs.

At the bottom line, Netflix’s substantial growth has driven its valuation to high levels. Its debt to equity ratio of 1.81 would put it in a more vulnerable position if the company were ever to hit a rough financial patch.

For investors looking to take a safe bet with a pipeline into the streaming space, investing in Disney may be the right choice. But for investors looking to take a chance on a streaming juggernaut may rather bet on Netflix.

Looking Ahead

Many analysts recommend selling a Netflix stock at the moment, in anticipation of subscriber losses. Netflix stock has lost its luster in the equity market as the company’s growth has slowed. How can it take a leadership role once more?

Netflix executives have said that they will not sell advertising on the platform to generate more revenue. However, Wall Street disagrees with this decision. Needham analyst Laura Martin recently downgraded Netflix’s stock to “underperform” but offered a solution including advertising. She claims that an option costing $5-7 per month, featuring six to eight minutes of advertising an hour, will help fend off competition. As other services are undercutting Netflix’s pricing model, a low-cost option may be a smart idea.

If Netflix sticks to its no-ad policy, it’s going to have to get creative. Perhaps it will begin to create mobile-centric content, following the soon-to-be-launched platform, Quibi. Maybe it will start to offer exclusive experiences, licensed merchandise, or build a theme park to diversify its revenue streams.

Either way, Netflix started out as the little DVD rental service that could, and if it can ride the waves of industry change as it has in the past decade, Netflix could indeed come out on top.