While the economy of Los Angeles is booming right now, finding an affordable place to live is increasingly difficult for many residents. If the mounting housing crisis is not addressed soon, the city’s future will likely be fraught with economic turbulence and crippling infrastructure.

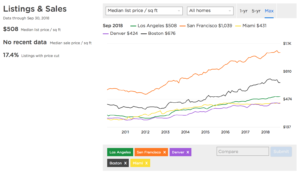

Data from the National Low Income Housing Coalition indicates that on average, a worker in 2017 would need to earn $29.71 an hour in order to afford a 2-bedroom apartment. In the case that a worker can’t find a job at that wage, they would instead have to work 113 hours per week—almost 3 times the number of hours worked by the average American—at California’s minimum wage rate of $10.50 in order to afford a 2-bedroom. Additionally, over the past year, the average price per square foot in Los Angeles rose 8.7%, from $584 to $635. And that increase is indicative of a larger upward trend in cost over the past few years.

Source: LA Times

Rising unaffordability should be a point of major concern. The higher cost of buying or renting pushes the working poor out of the housing market all together, leading them to slip into homelessness, and also keeps those without a home at all on the streets. It also is causing more people to leave California than the number currently moving to the Golden State. Plus, unaffordability means Angelenos are living further from where they work and enduring a grueling commute, which Alan Greenlee, Executive Director of the Southern California Association of Nonprofit Housing, notes has “all kinds of bad outcomes” ranging from greenhouse gas emissions to straining infrastructure. Thus, these implications equate to growing inequality and pose a long-term threat to the stability of the city’s economy.

Los Angeles is not alone. Rather, the city is one of many major metropolitan areas that is experiencing extraordinary unaffordability. In Denver, builders cannot keep up with the pace of migration into the city, which is one factor causing the housing market to slow. In the now notoriously-expensive Bay Area, the New York Times’ Karen Zraick reported in summer 2018 that the “the federal government pegs the ‘fair market rent’ for a two-bedroom in the San Francisco area at $3,121” where the median home price “has climbed above $1 million”. On the other side of the country, the majority of homes in Boston cost between $500,000 and $1 million. In Miami, the city offers only 26 affordable housing units out of every 100 extremely low-income (ELI) renter households, compared to a still-abysmal national average of 35.

Median list prices per square foot since 2011 in five U.S. cities that have experienced an unaffordability crisis (Zillow)

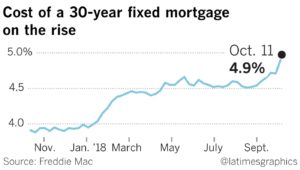

What’s causing the crisis in these cities? First, rising mortgage rates have made buyers wait to purchase homes, leading to less on the market and thus an increase in prices. Plus, residential investment has been falling steadily for three consecutive quarters across the country, meaning construction and brokers fees are continually shrinking.

In Los Angeles specifically, Greenlee says the housing affordability crisis can be traced back to “a pretty simple economic issue. Supply under-paces demand, and as a result, prices go up.”

Rising mortgage rates across the United States (LA Times)

One way to curb the higher costs that come with less supply may be through higher wages. Higher wages translate to more money in people’s pockets to spend on housing, and L.A. has set a progressive schedule for raising the minimum wage until 2020. However, Los Angeles Times writer Kerry Cavanaugh concludes that, “even $15 an hour won’t help much in Los Angeles as long as the cost of housing remains so high.” In the most recent quarter of 2018, annual home price appreciation was higher than weekly wage growth in Los Angeles, as it has often been recently. Thus, although wages are rising, prices are rising faster.

Another policy option to curb the crisis would be to increase rent control across the city. Recent research indicates that moderate rent control would stabilize rents, and thus overall help quell the crisis. Although rent control could help, even proponents acknowledge its only one of many necessary steps that should be taken. Plus, like raising minimum wage, it’s another strategy that merely puts a Band-Aid on the larger problem.

According to Greenlee and other experts, the ultimate answer to the crisis—and the only one that addresses the root problem—is to build more. Doing so would not only help to decrease housing unaffordability, but it would also address a connected epidemic in Los Angeles: homelessness.

Although homelessness is a result of many contributing factors, on the most basic level, “homelessness is primarily a housing issue,” says Dr. Benjamin Henwood, a professor at the University of Southern California and an expert on homelessness and affordable housing.

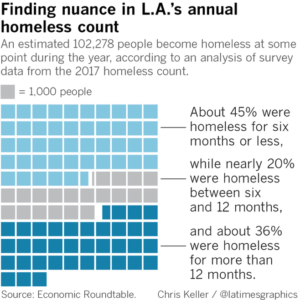

In Los Angeles today, homelessness is unavoidably obvious. Between 2012 and 2018, experts believe that homelessness in L.A. increased 75% from 32,000 to around 55,000 individuals. However, recent data by the Economic Roundtable tells a different story, with analysts finding that 102,278 people in Los Angeles became homeless at some point last year. Either way, the rise in homelessness is one of the clearest signs of a broken housing system.

Source: LA Times

Henwood argues that as a whole, “housing shortages will continue to undermine best efforts to address homelessness.” Although not all affordable housing addresses the needs of homeless individuals who are out of the housing market entirely, building more affordable housing in general would still help to curb both homelessness and housing unaffordability.

Research backs up this argument. In 2017, Zillow researchers found that the “relationship between rising rents and increasing homelessness is particularly strong in four metro areas currently experiencing a crisis in homelessness,” one of which was Los Angeles.

Source: Zillow

Therefore, greater supply and lower prices for Angelenos would help not just those currently searching for a home, but would also have the trickle-down effect of reducing the number of homeless. While a combination of tactics is needed to address homelessness, to address the larger housing crisis, building more homes is a good place to start for everyone.

Through the visibility of rising homelessness, Los Angeles has already taken some first steps to improve the greater housing crisis. After voters had to live and breathe in direct contact with the sprawling homeless population for a number of years due to changed regulations, they took action, and in November 2016 passed measure JJJ, which ensured that “if developers are going to make something, it had to include housing that was available for low-income people” says Greenlee. That same year, voters also passed Proposition HHH, which funded affordable housing through a bond program. And before that, the county in 2015 decided to dedicate $100 million a year to support affordable housing development.

According to Greenlee, those policy changes were driven by the fact that “people decided our current situation related to homelessness was intolerable.” While the programs in place have admittedly run into roadblocks, they are certainly steps in the right direction by Greenlee’s standards.

Looking ahead, the next steps are for policymakers to continue to promote and propose programs to fund affordable housing, and also to ensure they are properly executed. But beyond building rapidly and intentionally, Angelenos also need to get out of the way for real change to occur. Greenlee notes that one of the biggest impediments has not been to convince people to support propositions that would build affordable housing, but rather to coax people to accept greater density in their areas.

As an example, Greenlee noted a recent housing development program put forward by the mayor of Los Angeles, in which council districts would be required to create temporary housing. In some areas – like Koreatown, Venice, and Sherman Oaks – local residents met that proposal with furry, enraged that they would have to live in close contact with the homeless. Instead of standing in opposition, Angelenos should vocalize their support for greater density in their areas rather than—as Greenlee described— “going bananas” when they hear affordable housing is coming.

Protestors in Koreatown, Los Angeles reacting to plans for homeless housing in their area (LA Weekly)

While on the one hand, people want to be as far away as possible from the poor, many Angelenos are also worried about seeing a decline in the value of their properties if low-income housing is nearby. However, if the city is serious about solving the crisis, Angelenos need to acknowledge that the homeless likely already live in their neighborhoods—just on the street rather than inside—and that building more affordable housing helps not just those without homes, but everyone who is seeing skyrocketing prices due to extreme demand.

Citizens also need to educate themselves about the issue. Experts are generally in agreement that the most comprehensive solution to the crisis is to build more homes. But, a recent USC Dornsife/ LA Times poll indicates that many constituents believe the housing unaffordability crisis is a result of a lack of rent control. While rent control is an issue, this data indicates that people still don’t actually understand the crisis. If instead, Angelenos better understood the issue, they would perhaps be more likely to support additional legislation, and to accept shifts in the make-up of their neighborhoods as necessary.

As a whole, this is not the type of crisis that is impossible to solve. Rather, the solution is relatively clear, but the largest obstacle blocking the way forward is Angelenos themselves.